Understanding illness and careful adherence to a treatment protocol are important steps in working toward an improved state of health. Yet, statistics show that while most healthcare practitioners believe people understand their conditions and adhere to treatment, in reality that is not the case. Perhaps it’s time to re-define how we look at adherence in order to effectively address how to shift the paradigm.

Adherence, as it relates to medication and treatment, has been defined as, “The extent to which the patient’s behavior matches the agreed upon recommendations from the prescriber.”

It may seem obvious or even simplistic to start a discussion on adherence with definitions, yet the definition reminds us of something important. Adherence is not compliance. The terms are so often used interchangeably that it can be easy to forget there is a difference. That difference is the patient. Through this lens, we find key learnings for pharma, HCPs and all healthcare stakeholders.

Adherence views the patient as an individual who is an active participant in decision-making and care. The person is not simply someone who receives a directive and follows it. Rather, the person makes a conscious decision to agree with the HCP that this is the right treatment for them at this time and that she will participate in carrying it out.

What Adherence Isn’t

Understanding what adherence is also means understanding what it isn’t—a guarantee of persistence. A great chasm exists between understanding, acceptance, agreement and long-term persistence. Adherence isn’t simply a response or a reflex, and one of its benefits is bringing the patient along on the journey as an active participant. This means a simple reminder to take medication at a certain time isn’t enough to promote sustained results—it isn’t one size fits all. Instead, the approach to adherence needs to be as unique and personalized as the person taking the treatment.

It’s not often we can find commonality across diagnostic category and treatment modality. Yet, adherence, or perhaps more importantly, nonadherence, doesn’t discriminate. Acute illness or chronic disease, diagnosis and treatment type have very little impact on the challenges of adherence. On a playing field so broad, how do we begin to address the issue?

Begin With The Patient

The definition of adherence holds a key to the answer. If we agree that the patient is central to this issue, then the patient is the perfect place to begin. But we must look beyond the obvious descriptors of the patient—gender, socio-economics, age and even personality are only mildly correlated with whether or not a patient will adhere to prescribed treatment. The stronger factors surround an individual’s beliefs and perceptions regarding an illness or a treatment. Three key questions determining adherence include:

- Is the illness and treatment important to the patient?

- Does the patient feel at risk for further deterioration of their physical or emotional health?

- Is the patient willing and able to be an active participant in her care? And perhaps the most important piece of information is the follow up: Why or why not?

Patients engage in an ongoing analysis of the weight of barriers to adherence over the motivators. By assessing each individual patient, we can learn a great deal about what his/her motivators and barriers are for treatment adherence. In turn, this may help shape how we view adherence.

The World Health Organization’s definition of nonadherence is: “An unavoidable by-product of collisions between the clinical world and the other competing worlds of work, play, friendships and family life.” While it can be incredibly helpful for patients to evaluate and modify factors that act as barriers to motivation, it is critically important to recognize that patients do not operate from within a bubble. Time, energy and competing interests impact adherence. Family may (or may not) offer support, work demands can impact schedules, and reading info online or talking to other people all shape how a person may view an illness or treatment.

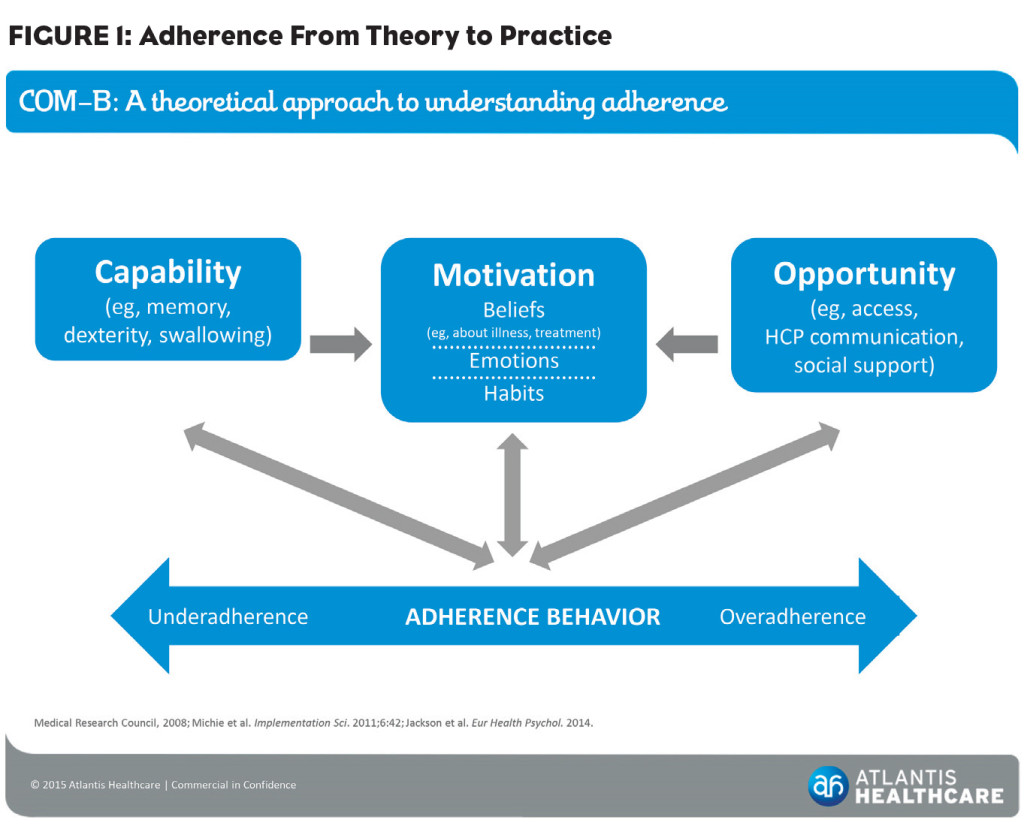

One model often used to account for this is the COM-B. This proven psychological framework enables us to look at factors including social support, HCP communication, access to medication and physical capability. We can then integrate these snapshots of the individual with belief-based concepts about factors like illness and treatment coherence, self-efficacy and treatment efficacy to paint a much broader picture of the individual and encompass additional potential adherence motivators and barriers.

It is undoubtedly beneficial for the patient to explore the contexts shown in Figure 1 in a methodological manner. Assisting patients to think about the concepts that may be barriers to adherence can help shape how they think—and not only about a current condition or illness, but also about their role in finding and receiving the best possible treatment and even achieving improvement in general health.

Pharma marketers, HCPs and other stakeholders stand to benefit greatly through patient adherence. The way we think about it may be enhanced, or even dependent on the patient’s ideas about their illness and treatment. Research across therapeutic categories demonstrates that HCPs who are interested in the diagnostic/treatment area and interested in adherence are more likely to have an ongoing dialogue about it with their patients. Yes—an ongoing dialogue. One and done isn’t enough. This dialogue, it turns out, is central to whether or not a good patient adheres to treatment—because a patient’s motivation can change considerably over time.

Understanding adherence, the critical importance of bringing patients on the treatment journey as partners and recognizing the differences between individuals enables us to make strides in improving adherence and in turn, make a significant impact on improving the health of the population.

Resources:

Horne R., Weinman J. (1999) “Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness.” J Psychosom Res, 47(6): 555-67.

Jackson C, Eliasson L, Barber N, Weinman J. (2014) “Applying COM-B to medication adherence.” The European Health Psychologist. 16(1), 7-17.

National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Delivery and Organisation R & D. (2005). “Concordance, adherence and compliance in medication taking.”

Nieuwlaat et al . (2014) Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014.

WHO. (2003) “Adherence to long-term therapies – Evidence for action.”