“Why does my team resist my plan for the future? My vision is clear, well supported and presented in a variety of formats?” The answer is embedded in the second sentence above. It only describes half the leadership task—advocacy.

If leadership is a combination of vision (knowing where the organization should be headed) and followership (getting your people to energetically follow you toward that goal), it’s the second element that this leader has trouble with. This is not to discount the importance of vision, for vision is certainly a rare commodity. If you are old like me, you will remember the criticism of George H. W. Bush and “the vision thing.”

While vision may be something of an innate ability, I believe that followership can be learned. The problem is that for most people it is counterintuitive to their understanding of effective leadership. Here is one reason why:

Leaders need to appear confident about their vision and plans. They do not want their team to think they are questioning their own judgment—George W. Bush said, “I won’t debate myself.” Many leaders thus worry that they would be abdicating their right and responsibility to lead. The leader might ask: “Since a good leader knows that some people will resist change no matter what, why provide them with an opening?” The limitation of this thinking is that it places undo pressure on the leader to “know everything.” Frankly, it is an antiquated idea of leadership, and highly unrealistic. The business world has become far more collaborative and team oriented.

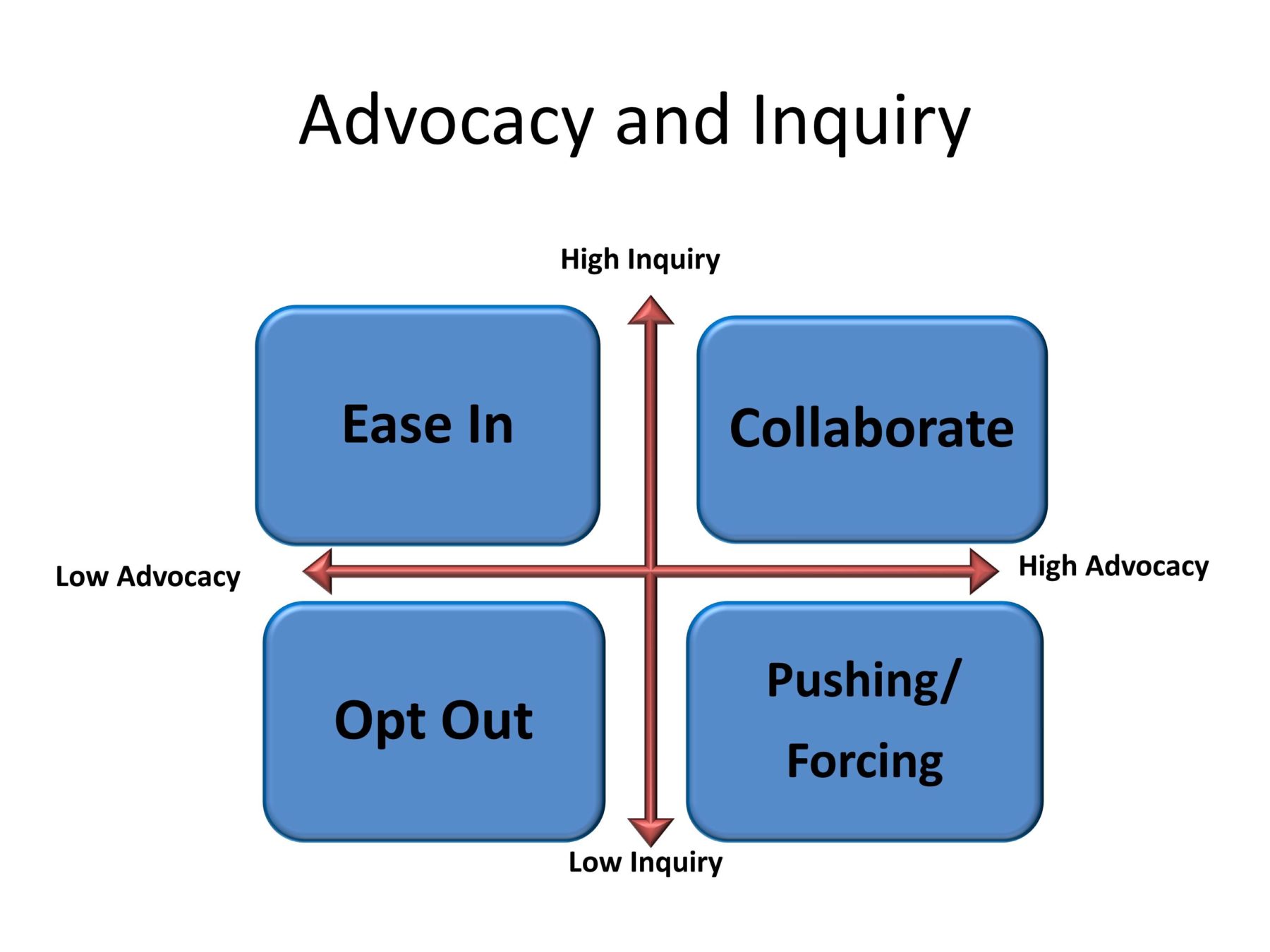

The answer can be found in a dynamic described by Chris Argyris and Donald Shon (Argyris, 1996) some 40 years ago. Simply, (probably simplistically, but it will suffice here) it is the need for both “advocacy” as illustrated above, and “inquiry.” Without inquiry, advocacy is just “pushing rope.” We all know how frustrating this dynamic is.

First we need to start with an explanation of what inquiry is. Inquiry here is described as a give and take questioning process that works toward augmenting knowledge and solving problems. It means making oneself open to real questions and also asking meaningful open questions of those who will be involved in and affected by the change. It does not mean responding to these questions with pat answers demonstrating that we know it all. It means taking these questions and challenges seriously. This is why it is so hard for so many leaders—they may fear that by asking questions and inviting challenges they are looking unsure of themselves. They may also fear that the inquiry will demonstrate the limits of their vision, or the problems that they missed. In short, they fear looking less smart and all knowing. “All knowing”—that must be difficult to shoulder!

A truly strong and confident leader is not afraid to ask questions. He or she will say, “This what I think, what are your thoughts?” For the best example I have ever read of a president who has done this well, take a look at Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (Goodwin, 2005). The title says it all.

Of course, how this inquiry takes place depends upon the audience to whom one is speaking. If the group is made up of a management team, the discussion can be both of a strategic and a tactical nature. As managers continue this process through the organization, the scope of the inquiry will change. It is probably of little value to ask someone on a bubble pack assembly line about corporate strategy, but it may be of great value to ask what manufacturing issues will arise with the change. On this topic, the people on the line will know a lot. It was this thinking that led to Ford Motor Company setting up quality circles in the 70s and 80s in response to Japanese car quality improvements.

In the above matrix, the result of high advocacy and inquiry is collaboration. This is not to suggest that leaders abdicate their special role, or that I am recommending a democratic process. But I am suggesting that there are far more options beyond dictating change and consensually developing it. The leader is primarily responsible for the company’s future strategic direction; but in the interest of “augmenting knowledge and solving problems” he or she should become more vulnerable to questions and questioning.

My students have said that they rarely see this advocacy-inquiry process with their managers. Despite years of organizational theory advancement, they still see mostly advocacy without inquiry. The result is that they find it hard to embrace change, and management is stuck pushing rather than pulling a rope.

References:

Argyris, C. (1996). Organizational Learning II. Burlington: Addison Wesley.

Goodwin, D. K. (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon and Shuster.