Physicians apply many different references when taking care of patients. In today’s environment, options range from classic, paper textbooks to online compendiums. With the addition of blogs and crowdsourced information, there are many places to get the needed information. The question is where do we—as physicians—go?

As a practicing physician in emergency medicine and critical care, I apply a diversity of references depending on the circumstance and patient in front of me. Having worked in many different medical settings, as well as interacted with and taught many physicians and physicians-in-training, I am acutely aware of which digital forums have replaced the classic textbooks. The type of references used changes depending on our experience and comfort. For example, if I need a quick reminder of a formula for a disease process, I could quickly look it up on one of the calculator websites. However, if I need to review a disease altogether, then I would use a more in-depth review or primary article, which I may access through PubMed or Cochrane.

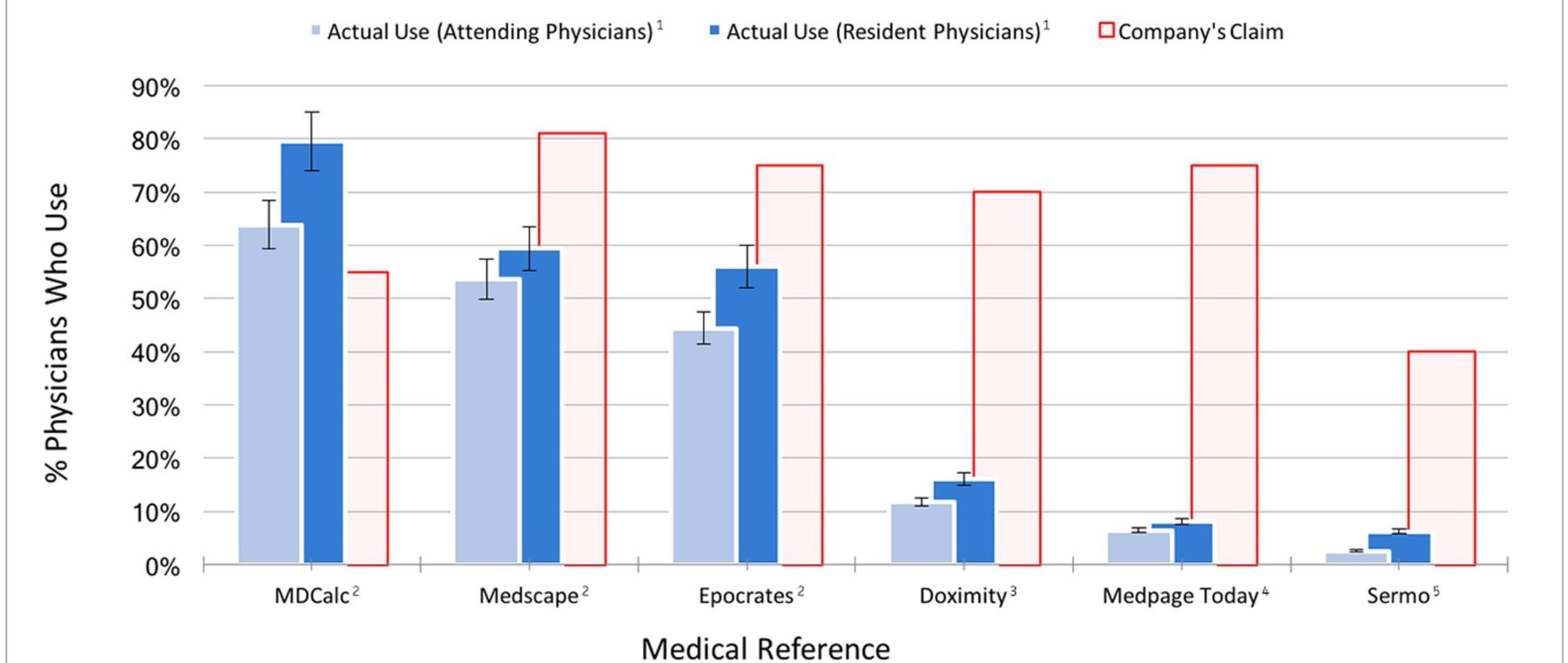

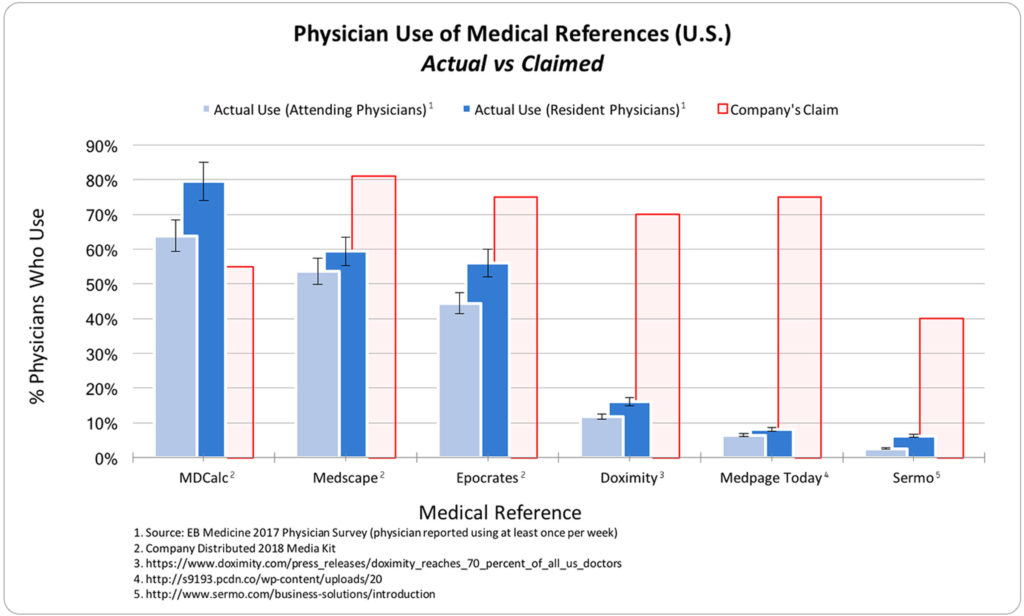

Often, companies running medical references publish their own claims of physician usage. A recent physician survey by EB Medicine, a popular evidence-based medical resource, measured the “actual use,” which drastically differs from the “claimed use.” The disparity ranged anywhere from 5% to 69% (see graph). These results were not surprising. From my experience, physicians essentially use four types of medical references when seeing patients:

- Modern versions of a textbook, such as UpToDate or Medscape.

- Drug reference guides, such as Epocrates or Micromedex.

- Medical calculators and clinical decision rules, such as MDCalc or ClinCalc.

- Original research and summary articles found from databases, such as PubMed and Cochrane.

Additionally, the more recent generation of doctors, including those who are currently in training, is sometimes using medical blogs and podcasts. However, care must be taken with these venues as there is a worry that opinion might be sold as fact.

Additionally, the more recent generation of doctors, including those who are currently in training, is sometimes using medical blogs and podcasts. However, care must be taken with these venues as there is a worry that opinion might be sold as fact.

So how do these references claim so many doctors use them, when we apparently do not? I realized that many of them regularly send us emails. Most, if not all, of these emails ultimately end up in a spam folder.