Many people believe the bio-pharma industry is oligopolistic, similar to the car or airline industries, with only a few huge players in the game. The reality, however, is that it is extremely fragmented with many players of all shapes, sizes and styles—with the largest ones commanding no more than a 10% or so total market share (depending how you calculate it). This is at the corporate level; of course, things are different at the therapeutic-area level where few players do tend to dominate or hold a substantial share (over 30%) of some therapeutic classes, but this is more of a time-limited dominance subject to product lifecycle pressures, pricing dynamics and generic cliffs, with somewhat different strategic implications.

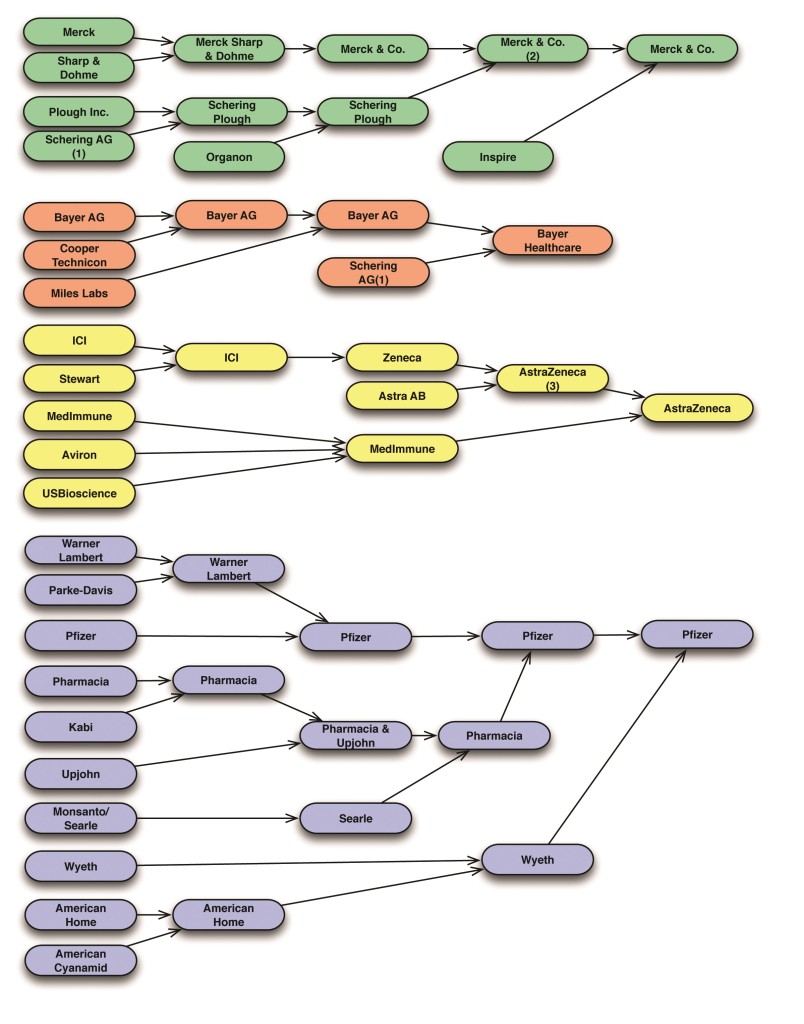

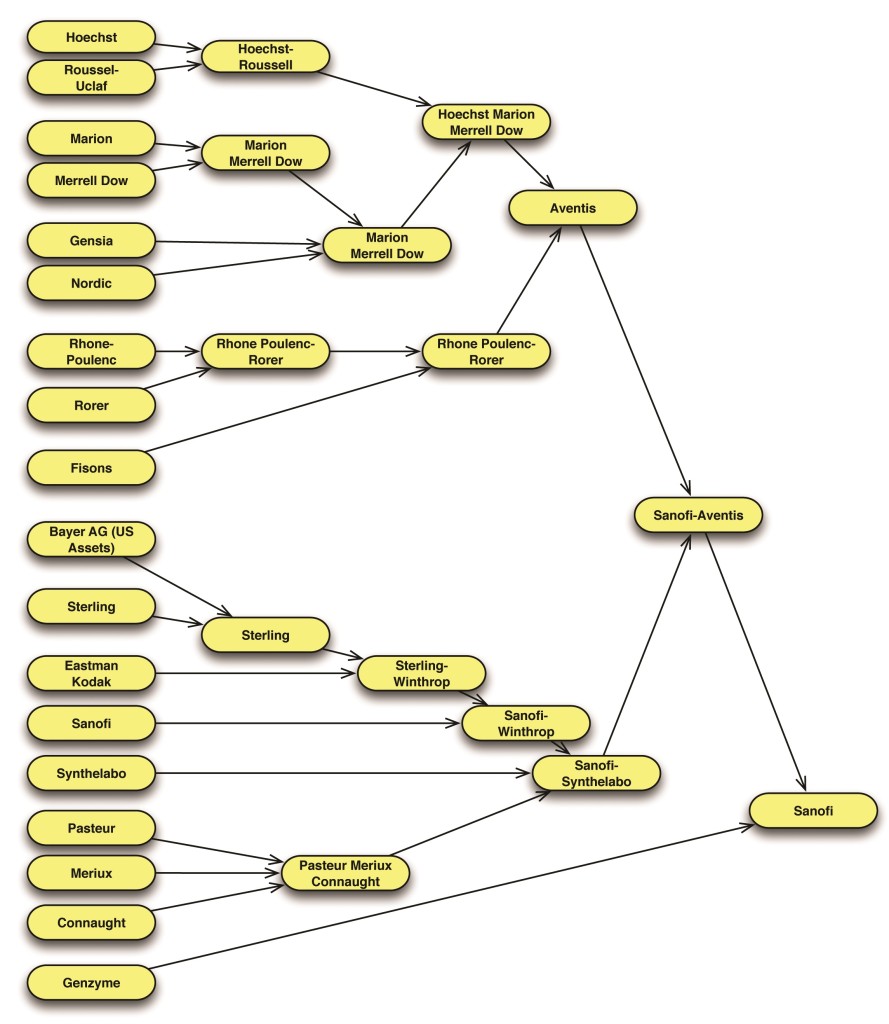

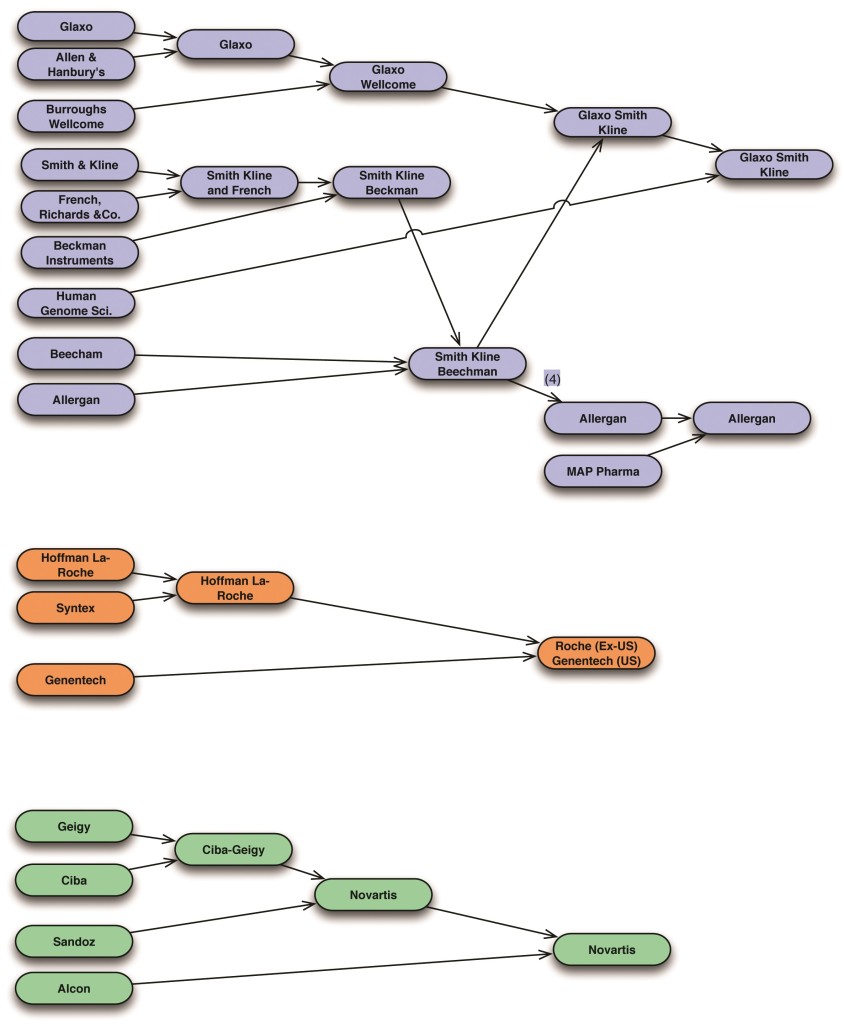

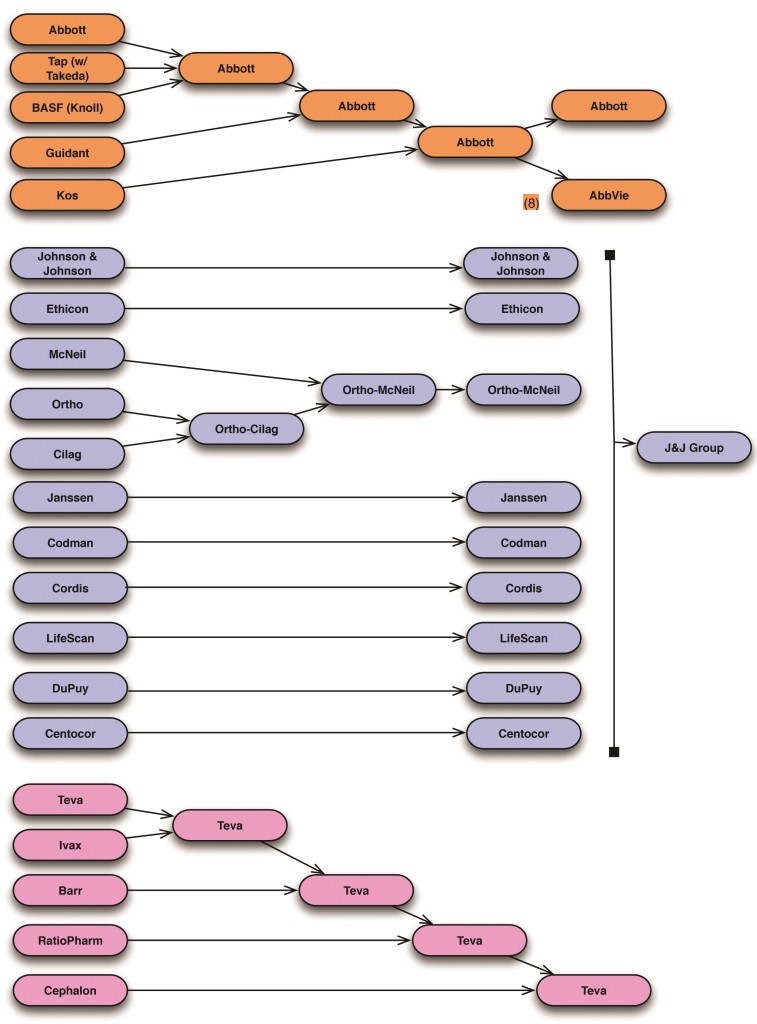

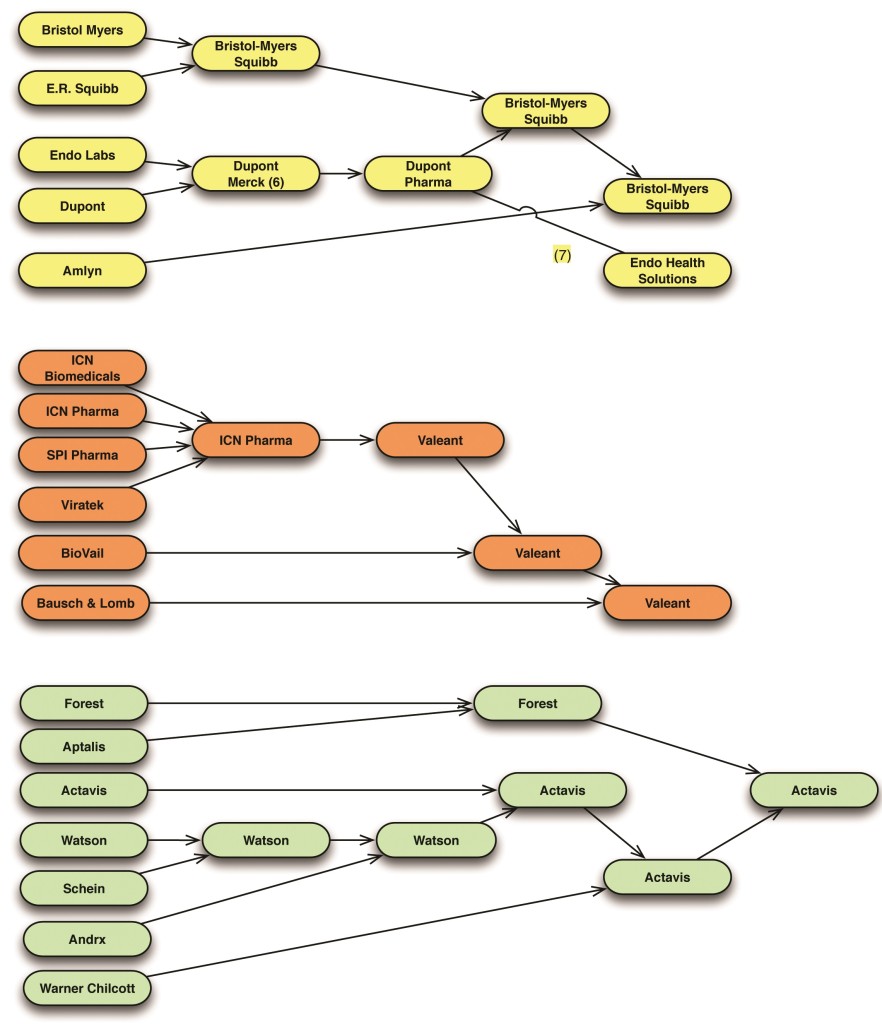

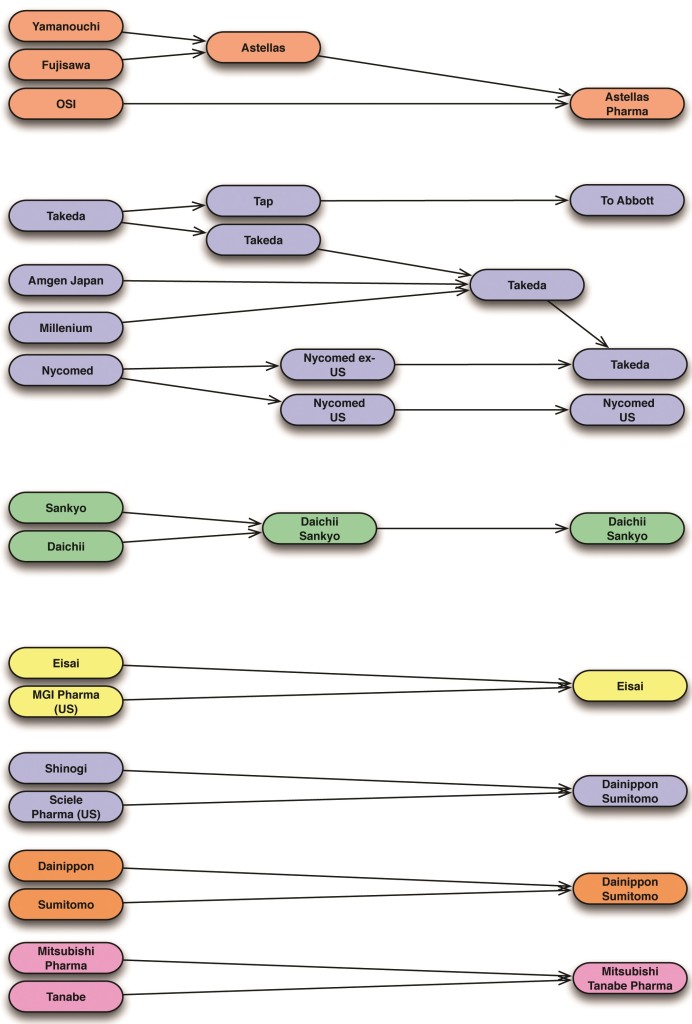

During the last 30 plus years we have seen a major consolidation in the industry through mergers and acquisitions. This article and, most importantly, the accompanying graphics, attempt to summarize and provide a retrospective look at how this consolidation has taken place over the years. This kind of review is not only intellectually thought provoking, and perhaps nostalgic, but also gives a sense of the range of strategies that have been employed across the board. Moreover, it highlights the types of strategic choices that seem to be preferred by certain companies or groups. Some prefer sequential acquisitions of smaller players; some turn to sequential acquisitions of similarly sized companies; and others tend to like mergers of industry behemoths. We have also seen a renewed appetite for disinvestments and break-ups.

One remarkable conclusion in the analyzed cohort is that approximately 110 companies have consolidated to about 30; in other words, the absorption along the way of some 70% of companies that have existed in a relatively short period. One casualty has been the loss of many jobs, especially in non-customer-facing roles that tend to be duplicative among companies coming together; though we have also seen major reduction in customer-facing functions as, among other dynamics, companies combine portfolios and product assignments.

A Few Observations

As one would expect, in the earlier days of this trend, the tendency was to consolidate nationally before going abroad. For example, British companies such as Glaxo, Welcome and Smith and Kline converged first; the same can be said for French, American, Japanese and, to some extent, Swiss companies within their respective home countries. Presumably, this was seen as low-hanging fruit permitting easier cultural integration, operational efficiencies and more. Their moves were also facilitated by local laws, sentiments and political appetite. As these intra-national combination opportunities became exhausted, and as companies became more globally minded, they started looking for M&A opportunities elsewhere and, as a result, we have seen a lot more multi-national and global activity.

The U.S. market has been and continues to be the most attractive. The size of the market, the appetite to adopt new products, the relative ease to obtain reimbursement, and the relative lack of active and monolithic price controls has invited companies to grow in the U.S., first by establishing smaller entities and later by combining in one way or another with other companies in order to achieve a critical mass suitable for the market. Examples are all of the Japanese companies and some of the European ones such as Astra and Pharmacia.

Johnson & Johnson has maintained a unique style all along, in which the strategy includes acquisitions but, unlike the rest of the industry, it has preferred to keep each company relatively independent and separate under the overall J&J group, which operates largely as a holding company.

We’ve also seen the gradual entry and subsequent exit via asset sales or spin-offs by large chemical companies such as DuPont, Monsanto, BASF and Dow Chemical, none of which currently have significant bio-pharma businesses, except maybe in supplying intermediates for research and manufacturing, a different business in every way.

Another couple of interesting spin-offs have happened, which may be the start of a new trend. As some companies become very large and many of their products are exposed to slow growth, maturing markets and generic competition, they have opted to break off pieces of their businesses into parts that ostensibly have different revenue, profit and growth profiles, as well as future prospects. This has happened with Abbot spinning off AbbVie and Pfizer reorganizing into three groups, possibly in preparation for a similar spin-off. This type of activity is also evident as companies move to break off OTC and animal health businesses which, although closely adjacent to the core business, have very different features and profiles.

Finally, of particular interest is the arrival, seemingly out of nowhere, of a company like Valeant. A small Canadian company formed by the consolidation of three tiny companies, then buying Biovail and more recently Bausch & Lomb. As of this writing, they are also pursuing the unsolicited purchase of Allergan. With this transaction, Valeant, from its modest headquarters in Quebec, would become quite a global powerhouse. Another new name, also seemingly out of nowhere, is Actavis, with a legacy of Forest, Watson and Schein, among others.

As of this writing, there are yet more interesting moves with Novartis, GSK and Lilly trading, mixing and matching pieces of their business; Merck selling its OTC business to Bayer; and Pfizer making an unsolicited move on AstraZeneca which has rejected every proposal Pfizer has sent its way.

Five Trends to Watch

1. The re-organization and break up of companies to allow the most innovative and dynamic parts of their businesses to thrive and not get bogged down or diluted by the rest of the product line—which may have different valuation drivers.

2. Along these same lines, we may see the formation of multiple small companies under an overall umbrella. Presumably this would allow for a degree of independence, speed and innovation. One can call this the J&J model.

3. The arrival and expansion of relatively unrecognized players in the innovative sector such as Actavis, Israeli companies (e.g., Teva) and Canadian companies (e.g., Valeant).

4. The arrival and expansion of Indian companies is still a big question beyond their established and ever-growing generic lines. Much has been said and speculated but little has transpired.

5. The appetite for big players to buy other big players will continue. Often these moves are driven by a desire to combine product lines and sales revenues, while at the same time dramatically lowering the costs of the combined companies through the removal of human and capital duplication.

History of Bio-Pharma Industry Consolidation

The below graphics provide a guide to many of the M&As that the bio-pharma industry has undergone. Before you review the graphics, here are a few quick notes:

- For simplicity, the graphics are intended to denote overall and approximate sequence of events and not precise timing.

- A best effort was made to be accurate about the general sequences of events and names of companies. Sources include historical records, press releases, news articles, investor reports, direct experience and industry memory. Errors and omissions are possible and, by publishing this summary, we hope to make corrections and ensure an always-updated summary.

- This is not intended to be a complete set of mergers and acquisitions. The focus is on companies with marketed or about-to-be-marketed products.

- As this is a very dynamic field, changes may happen even before this article gets published and some will happen soon after. Depending on the frequency and extent of new activity, we hope to update the summary graphics from time to time.

Footnotes:

Notes on certain transactions from the above graphics:

1. Asset split between Schering and Schering AG.

2. Technically the acquisition was Schering-Plough buying Merck & Co., reportedly to avoid triggering a change of control clause in the agreement between Schering-Plough and Johnson & Johnson for Remicade. Essentially Merck & Co. became Merck Sharp & Dohme; Schering Became Merck & Co. and with the paper acquisitions, Merck & Co. lives on.

3. Includes AstraMerck in the U.S., the venture between Merck and Astra to establish a new U.S. entity.

4. Allergan acquired by SKB in 1980, later spun-off in 1989.