In a bold update made at the beginning of 2020, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) said it would now accept real-world evidence (RWE). Similarly, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now uses RWE and real-world data (RWD) to monitor post-market safety and make regulatory decisions, and has provided guidance to companies for its use in various types of studies. Life sciences companies see this as a win because they contend that RWE shows the value of their products beyond data from the randomized clinical studies that are the gold standard for regulatory approval.

Once an afterthought, RWE is quickly becoming core to many drug makers’ efforts to prove the value and safety of their products. New technologies such as wearable devices and the uptick of decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) in place of traditional randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have helped make gathering the vast amounts of data required for RWE more feasible.

The Inequality in Clinical Research

One argument for the use of RWE to supplement RCTs is to reduce the racial disparities that are pervasive in traditional trials today. The FDA’s 2018 Drug Trials Snapshots show that only 38% of all oncology trial participants were women, 68% were white, 15% were Asian, 4% were black or African American, and 4% were Hispanic. These proportions sharply contrast with the racial distribution in the general U.S. population (76.6% white, 13.4% black or African American, 5.8% Asian, 18.1% Hispanic or Latino).1 Further, only 34% of participants in trials for cardiovascular drugs were female even though cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death for women.2

The COVID-19 crisis now casts a glaring spotlight on the inequity in healthcare and clinical research where racial, ethnic, and gender minorities have fewer opportunities to participate. “It appears that black patients were underrepresented in the COVID-19 clinical trials of remdesivir,” stated a press release, “even after adjustment for baseline severity, black patients were less likely to receive remdesivir.”3 And, Genentech’s Chief Diversity Officer Quita Highsmith said, “The COVID-19 public health crisis is amplifying health disparities that have negatively impacted communities of color for decades.”4

Clinical trials give access to investigational therapies to treat diseases—an opportunity that should be made equally accessible to all. Additionally, clinical study diversity is critical for researchers to understand whether investigational therapies are safe and effective for a broader set of patients—or whether differences in race, gender, and ethnicity might impact a drug’s safety and efficacy.

One silver lining of this pandemic has been the life sciences industry’s accelerated move to adopt new technologies that can capture RWD to generate RWE that will ultimately enable patient-centric trials inherently inclusive of all. America is long-overdue to embrace the words of its founding fathers and pursue equality. More human lives are at stake if the life sciences community doesn’t act now.

How RWE Advances Can Help

In clinical practice, patients are demographically diverse, their comorbidities vary, and their disease(s) can be clinically heterogeneous. Determining the long-term balance of risk and benefit for a treatment often requires representative populations that include large numbers of clinical events to examine the treatment’s complexity and variability, which is difficult to achieve with traditional RCTs. These factors, among others, explain the discrepancy between the evidence generated under the well-controlled but artificial RCTs and their effectiveness in the real world of clinical practice.

“RWE allow us to focus on a broader population than traditional research,” says Matthew Gordon, Vice President of Real-World Evidence at Worldwide Clinical Trials, a contract research organization with offices in more than 30 countries. “It’s a powerful way that allows researchers to look at different racial groups that don’t typically participate in clinical trials.”

More specifically, the inherent hurdles with traditional trials make it more difficult for patients in depressed socio-economic situations to participate. For instance, taking time off from work or away from childcare responsibilities to visit far-away clinicians can make trial participation impossible. The travel alone can be cost-prohibitive. Additionally, a lack of regular physician visits due to poor or no insurance coverage means that some populations are not aware of clinical trials even if they are happening in their own backyards.

The use of RWE, however, enables a more representative sample because researchers can have statistically matched “pairs” of data. For example, if an investigational drug is administered to a 25-year-old African-American female, it could be matched with RWE data from groups of similarly aged African-American women living in similar environments to serve as the synthetic control arm for the study and simulate clinical trial responses. Since it is often too difficult to enroll all of these individuals in a trial, the use of RWE provides researchers some additional context for evaluating a new drug’s potential impact on a more diverse cross-section of the population.

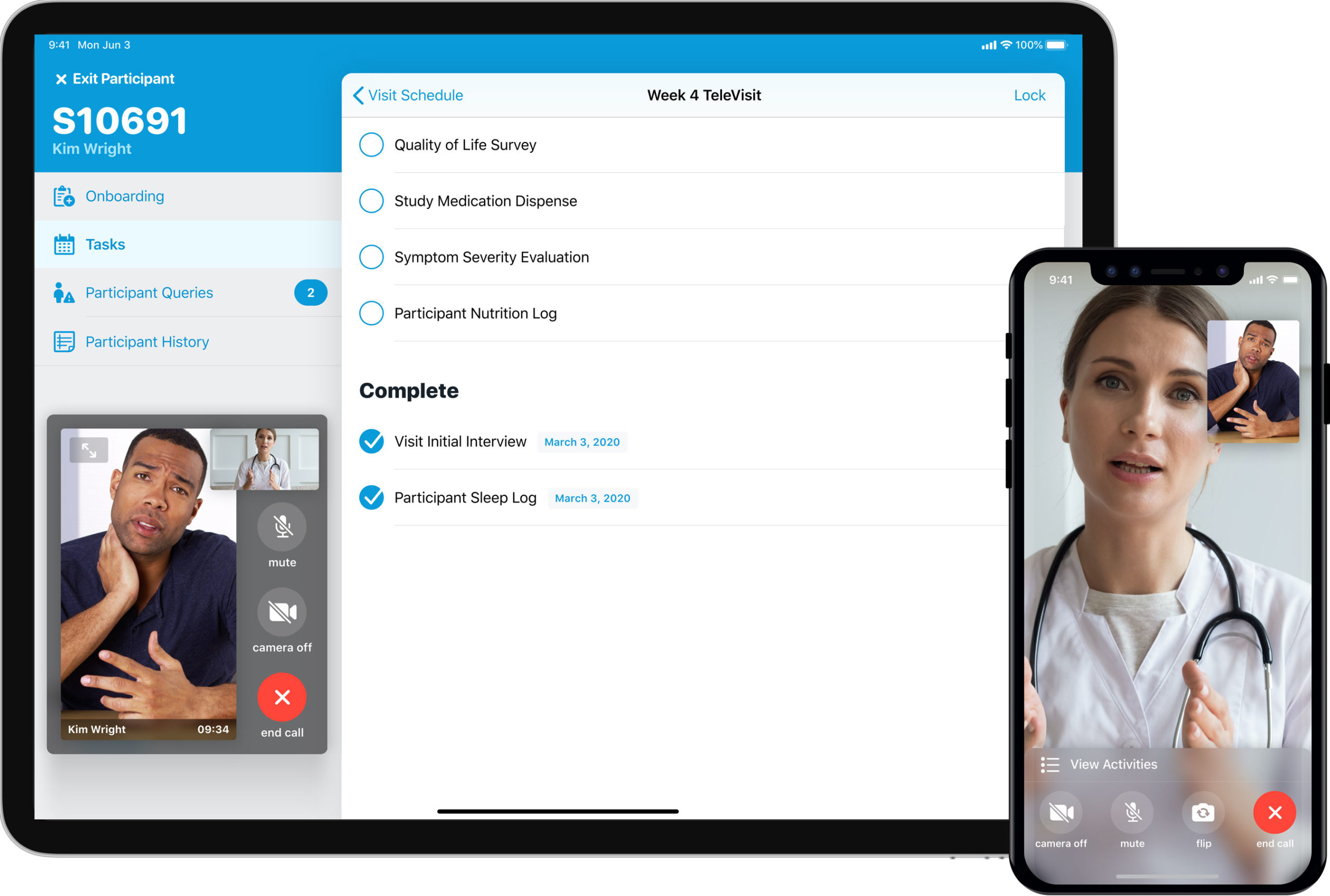

Virtual or DCTs that capture RWD directly from patients “in the moment” further enables diversity in clinical studies by allowing patients to participate from wherever they are, removing the barriers of travel and geography. This also offers the added benefits of accelerated enrollment and increased retention because it makes participation more convenient and feasible to all demographics.

In fact, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) found that a decentralized trial model recruited three times as many patients as the traditional RCT model, three times faster.5 The patients in the decentralized model also better represented urban and rural areas, whereas the traditional model only consisted of those living near an existing clinical trial site.

These benefits apply to trials across all disease states, but are particularly important for rare diseases, as trials are few and far between and participants may be spread across wide geographic areas. Patients are often willing to travel for an initial assessment and final visit—the bookends of their trial experience—but need to maintain their day-to-day life without the burden of frequent site visits, which is only possible in a decentralized model.

Overcoming RWE Challenges

While the industry is leveraging RWE and RWD more today than ever before, two challenges stand in the way for more widespread use: data volume and data privacy. In order to incorporate a synthetic control arm of RWE, companies need access to very high volumes of patient data across demographics, which leads to ethical considerations around data privacy.

Does the patient own his or her own medical data? The hospital network? Under the revamped European Data Protection Regulation (applicable as of May 25, 2018), companies can request a patient’s data but must go through tremendous administrative entanglements. Fortunately, technology companies such as Google are working to create an easier option—a password-protected electronic vault containing every patient’s medical information.

Patients would have the freedom to opt to donate their data to research groups or not, overcoming the data privacy concerns. While data privacy issues are still being discussed, companies can leverage the decentralized trial model to capture permissible patient data virtually about their experiences using a particular drug. New digital technologies and DCT platforms make this process easy for patients and efficient for researchers.

For example, patients in DCT trials can be given electronic diaries to fill out as needed to chart their progress or note any unusual issues of an experimental drug that might not be tracked as part of the study’s protocol.

“There has been a proliferation of real-world data in the last three to five years, and the sources of that data are multiplying as quickly as it is being used,” adds Gordon. “I don’t think this will slow down any time soon, either. Trial sponsors recognize the importance of implementing RWE earlier in trials, especially in decentralized trials, and its value in commercialization.”

Ultimately, RWE deserves the chance to be tested in different scenarios to see if it can effectively remove racial disparities. RWD sets from DCTs and RWE allow researchers to remove some of the underlying biases and analyze information based on a representative population for treatments that are safer and more effective for all. Additionally, using digital tools to track how therapies impact different groups in real life early in a trial, allows researchers to adapt the study midway to analyze these effects sooner—an advantage that benefits everyone.

References:

1. American Society of Clinical Oncology, Educational Book #39, “Enrollment of Racial Minorities in Clinical Trials: Old Problem Assumes New Urgency” (May 17, 2019). See full resource at https://bit.ly/3imqsRC.

2. American Journal of Managed Care, In Focus (blog), “Women are Still Underrepresented in Clinical Trials for Cardiovascular Drugs,” by Kelly Davio (May 2, 2018). See full resource at https://bit.ly/337MTTS.

3. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, VUMC Reporter, “New CCC19 Data Offer Insights on COVID Treatments for People with Cancer [press release]” (July 22, 2020). See full resource https://bit.ly/3bH86YI.

4. Genentech, “A Call for More Inclusive COVID-19 Research [statement],” by Quita Highsmith and Jamie Freedman (May 22, 2020). See full resource at https://bit.ly/2F5HLrJ.

5. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), “Building Clinical Trials Around Patients: Evaluation and Comparison of Decentralized and Conventional Site Models in Patients with Lower Back Pain,” (June 28, 2018). See full resource at https://bit.ly/3hd6s2d.