How can you convince anyone who is still hesitant about getting the COVID-19 vaccine to change their mind? That question is being asked by healthcare professionals, life sciences companies, and governments as the Delta variant of COVID-19 is causing an uptick of cases across the world.

It was also a question ZS, a global consulting and professional services firm, was interested in finding answers to. To explore how commercial behavioral science could help move people from hesitancy to willingness to get a vaccine, ZS tested 19 cognitive biases across more than 6,300 adults in seven countries (United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, United Kingdom, and Japan). The study examined three branches:

- vaccine hesitancy specific to COVID-19

- general adult vaccine hesitancy for proven vaccines, including shingles, human papilloma virus (HPV), and pneumococcal

- pediatric vaccine hesitancy and whether parents who are vaccine-hesitant would allow their children to receive recommended vaccines

The goal: identify mental shortcuts that could be used when engaging with vaccine-hesitant people to nudge them in positive ways toward a willingness to get vaccinated. But one of the most surprising findings was also discovering what did not work.

What Not to Do

“We tested a lot of tactics that we see commonly used to try to improve vaccine acceptance and a couple of them actually backfired,” Jacob Braude, leader of ZS’s applied behavioral insights practice, told PM360 in an interview. “For example, in terms of the COVID vaccine we found that authority figures don’t really push vaccine-hesitant folks successfully. In fact, we even asked people to name a person they personally trusted—with responses including Dr. Anthony Fauci and Sean Hannity—and then later asked how likely they would be to get the vaccine if that person recommended it. That still didn’t work.”

Sticking with the COVID vaccine specifically, another common tactic that did not move the needle was repeating the same messages of safety and efficacy from multiple sources. Additionally, using person-specific examples of other people who got the vaccine was not more compelling than using general population data.

In terms of the other branches tested, one tactic that failed to convince hesitant parents to vaccinate their children was the licensing effect. In this instance, you try to unconsciously balance good and bad behavior, such as reminding parents that they sometimes give their kids too many sweets as a way to make them more willing to practice preventative health behaviors for their kids. But that actually made parents feel less like their kids needed to be vaccinated.

Meanwhile, for general adult vaccines using a hyperbolic discounting tactic proved unsuccessful. For this tactic, you try to position something as a future event to make it seem more doable, such as telling someone they have to schedule their vaccination today, but it wouldn’t actual be until a few months from now.

So, if these tactics proved unfruitful, which ones actually work?

Triggers to Improve COVID Vaccination

When it came to the COVID-19 vaccine, seven bias triggers were shown to encourage vaccination.

1. Prospect Theory: People value something more if they feel they have won it. As an example, you can tell people, “We did a drawing and your name came up. We’re holding a vaccine for you if you want to come down and get it.” According to Braude, just making people feel like somebody took this out and put it aside for them helps encourage them to take it. While including prizes such as money, motorcycles, guns, etc. would fit under Prospect Theory, Braude says that the test they performed included no extra incentives and simply worked by positioning the vaccine itself as the prize. This tactic proved effective for most demographics, except white men.

2. Effort bias: People avoid activities that require a lot of effort. But by communicating a simpler process for getting a COVID-19 vaccine, it will increase the likelihood of people getting it. This proved especially effective for people of color and low-income groups.

3. Confirmation Bias: People seek out information that reinforces what they already believe and ignore other perspectives, but this can be mitigated by perspective taking exercises. “This is one of my favorites,” Braude explains. “I’ve been using it a lot myself, and really all you need to do is ask the hesitant individual, ‘Why do you think somebody would want to get vaccinated?’ This just opens the door and lets it play out in their own mind, which can be more effective then trying to persuade them yourself.”

For example, doctors could ask their patients to write down reasons why someone else would choose to get the vaccine. Or campaigns on social media could invite people to think about things from the other side’s perspective. This tactic worked best for men under 50, people who are living in urban environments, and people who are employed full-time and reside in cities.

4. Halo Effect: People tend to associate positive impressions and feelings of one thing with another, even if they are not directly related. “Whereas authority figures did not work, using trusted locations did,” Braude says. “When we asked people to name a place they trusted—churches, the fire department, pharmacies, dental offices were all trusted locations for certain groups of people—we saw an increase when we told people they could get vaccinated there.”

5. Social Facilitation: People tend to behave differently when they are aware they are being observed by others. For example, when French President Emmanuel Macron mandated that you need to be vaccinated to go to a cafe and hang out, there was a bum rush in France on vaccines. “Social consequences and that awareness of your status can be very motivating, in particular for people in cities and also working women,” Braude offers.

6. Anchoring Effect: People judge things differently in isolation than they do side-by-side. “In our test, we told people you can get a vaccine today that has 80% efficacy or you could wait eight months to get one with 95%. And we got a large chunk of people who are willing to go around unprotected for eight months in order to get that extra 15%, which you could argue is pretty negligible,” Braude explains. “So, we need to be careful about the way we position these different options in order to maximize the number of folks who are willing to get vaccinated right now. For example, by anchoring around the number of doses instead of the efficacy we may have seen the same effect.”

7. Effort justification: People believe when they put a lot of work into something, the outcome is more valuable. “In this case, when we reminded people about all of the effort that they put into staying safe from COVID or working from home or having to put their kids through school virtually, that increased their intent to get vaccinated, particularly among dads and young folks,” Braude says.

Furthermore, tactics are more effective when they are used together. In fact, the study found that 33% of the hesitant population could be moved to get a COVID-19 vaccine by combining the top six biases.

“Everybody has a different mix of these mental shortcuts that they use without even recognizing it to help guide decision-making,” Braude explains. “So, it is important to layer on the bias triggers in any sort of campaign in which you’re going to hit a large group of people in order to get the biggest effect. For example, we’re working with a group in India that tried to do vaccinations at a Hindi temple in a town where most people were Muslim or Christian. Most people didn’t show up. They shifted that to a trusted location and used prospect theory by saying ‘Hey, we only have so many vaccines. Do you want a vaccine?’ as well as by giving out free Biryani. During the first attempt at the temple, they had 150 doses and only vaccinated like five people. In the second attempt, they got rid of all the vaccines that they had available in that day.”

Braude adds that they could have layered on additional tactics as well. For instance, communicating how easy it would be to get vaccinated there in order to take advantage of effort bias or using social facilitation by putting up a banner where people could take a picture to show they got vaccinated to post on social media.

Tactics to Improve Other Vaccinations

Just because those tactics worked to encourage COVID-19 vaccination, that doesn’t mean those same tactics would work for other vaccines.

While social facilitation and confirmation bias were the third and fourth most effective tactics to encourage general adult vaccinations, the first two were entirely different triggers. First was social norms, where describing vaccines as a norm makes hesitant people more likely to get them. Second was commitment bias, in which getting people to publicly commit to a vaccine can make hesitant populations more likely to get vaccinated. Combining these tactics helped push 16% of adults to get a general vaccine.

Meanwhile, for hesitant parents, social norms, commitment bias, effort bias, and confirmation bias were the top four triggers to use to convince them to get their child vaccinated. But the fifth tactic was in-group bias. In this instance, if people feel that their racial group is represented in clinical trials for a vaccine, they feel more comfortable allowing their child to get one. Combining the top five biases moved 36% of respondents to “willing” to give their child a pediatric vaccine.

Why did some of these tactics work for one kind of vaccine, but not for another?

“Honestly, I wish we knew the answer,” Braude says. “I think that the science isn’t evolved enough yet. What we know is that different mental shortcuts work for different behaviors. However, it’s not clear to me what’s different about those decisions that makes those bias triggers effective or not effective, but it does reinforce the importance of doing the research first to figure out what to target so that you’re not either wasting your time or actually harming your objective.”

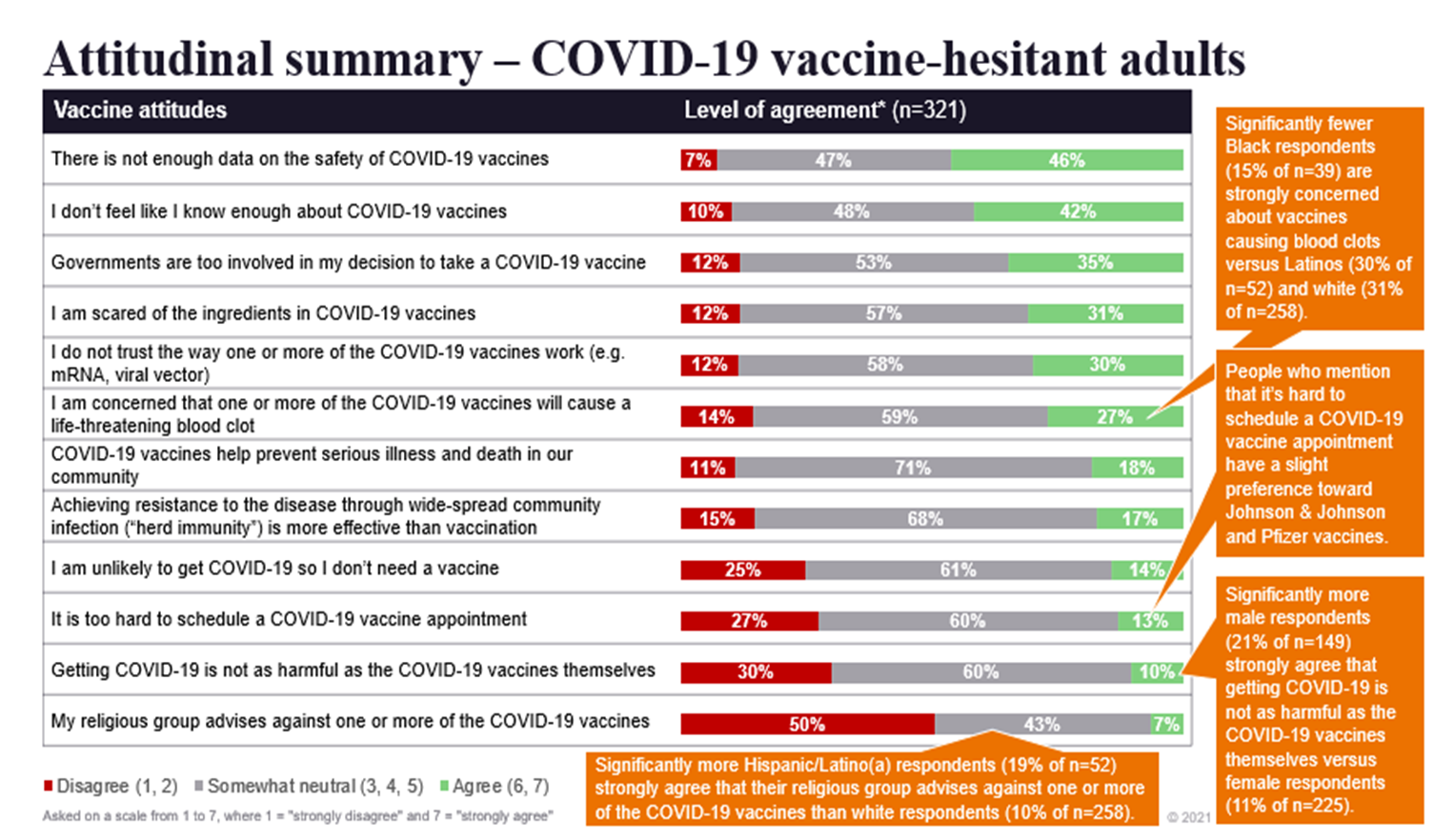

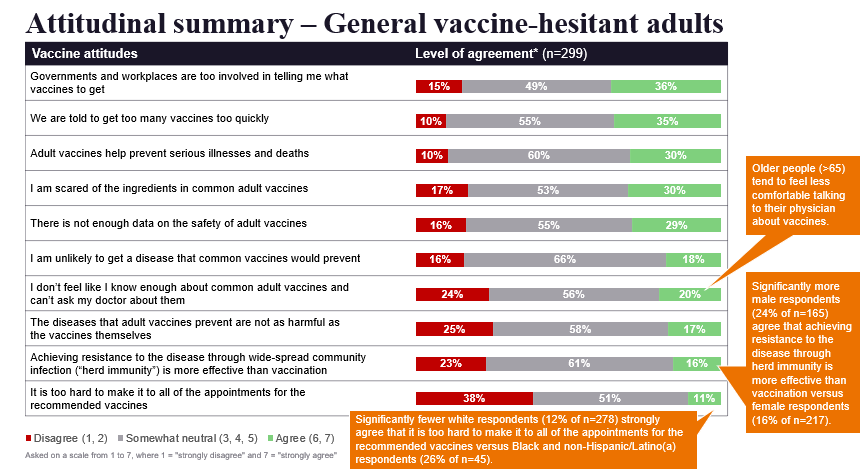

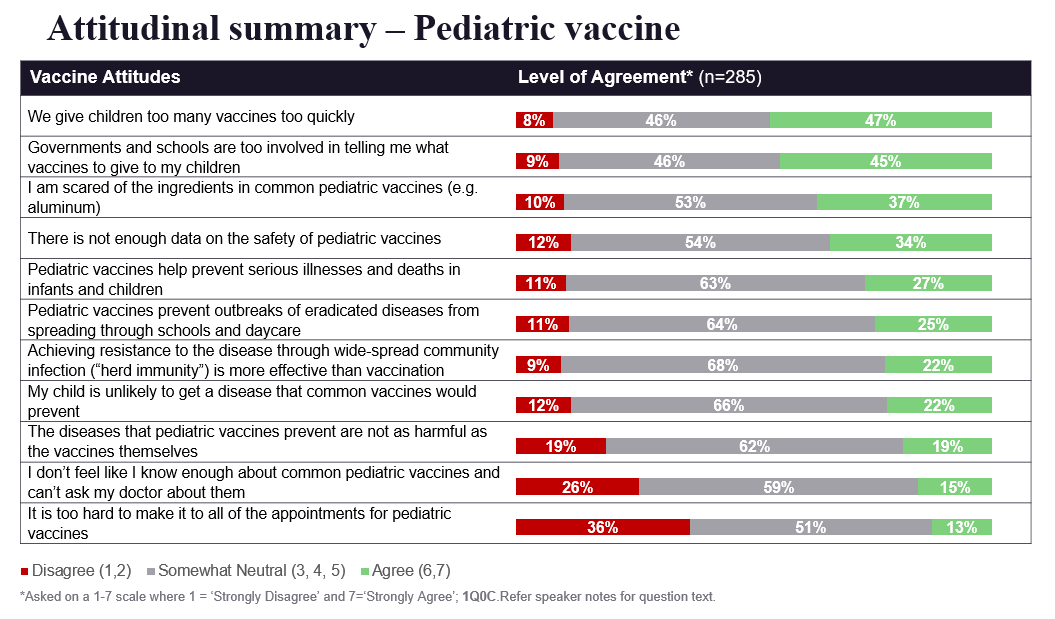

Examining Vaccine-Hesitant Attitudes

For each of the three branches, ZS also dove into people’s attitudes about the various different vaccine types and the reasons why they were reluctant to get each one. In the charts below, you can see a summary of those findings for the three different arms examined.

“What really jumped out is we got the same exact excuse for all three arms,” Braude explains. “Every single group suggested they would need to see long-term data that the vaccine is safe. And we have oodles of long-term data for pediatric vaccines and adult vaccines. While you could make the argument that we don’t have that long-term data with the COVID vaccine, I think the fact that we see the exact same percentage of people saying the same thing in all three arms points to the fact that this is a rationalization. This is something people can say that makes them sound reasonable when they say no to the vaccine, but it’s not actually what would make them feel comfortable with accepting it. That’s why I believe some of these unconscious nudges are going to be more effective than trying to generate that long-term data. Because we could have 20 years of long-term data and these people still wouldn’t be persuaded, but they could be nudged.”

“What really jumped out is we got the same exact excuse for all three arms,” Braude explains. “Every single group suggested they would need to see long-term data that the vaccine is safe. And we have oodles of long-term data for pediatric vaccines and adult vaccines. While you could make the argument that we don’t have that long-term data with the COVID vaccine, I think the fact that we see the exact same percentage of people saying the same thing in all three arms points to the fact that this is a rationalization. This is something people can say that makes them sound reasonable when they say no to the vaccine, but it’s not actually what would make them feel comfortable with accepting it. That’s why I believe some of these unconscious nudges are going to be more effective than trying to generate that long-term data. Because we could have 20 years of long-term data and these people still wouldn’t be persuaded, but they could be nudged.”