The recent spike in Zika virus cases in Central and South America brings with it the alarming risk – and even the expectation – of outbreaks occuring in the United States. How should U.S.-based clinicians prepare for the inevitable?

“The current outbreaks of Zika virus are the first of their kind in the Americas, so there isn’t a previous history of Zika virus spreading into the [United States],” explained Dr. Joy St. John , director of surveillance, disease prevention and control at the Caribbean Public Health Agency in Trinidad.

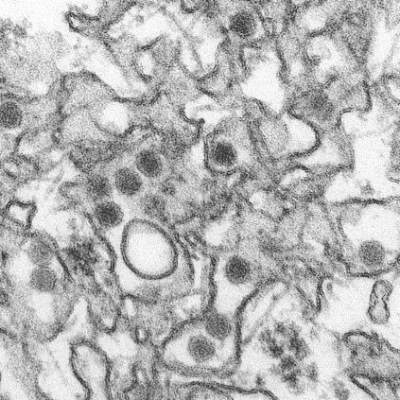

But now that the virus has hit the United States, with a confirmed case in Texas last week and more emerging since then, Dr. St. John said the most important thing is for U.S. health care providers to recognize the signs and symptoms of Zika virus infection. Carried and transmitted by the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito, Zika virus symptoms are relatively mild, consisting predominantly of maculopapular rash, fever, arthralgia, myalgia, and conjunctivitis. Only one in five individuals with an Zika virus infection develop symptoms, but patients who present as such and who have traveled to Central or South America in the week prior to the onset of symptoms should be considered likely infected.

“At present, there is no rapid test available for diagnosis of Zika,” said Dr. St. John. “Diagnosis is primarily based on detection of viral RNA from clinical serum specimens in acutely ill patients.”

To that end, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can be conducted on serum samples collected within 3-5 days of symptom onset. Beyond that, elevated levels of IgM antibodies can be confirmed by serology, based on the neutralization, seroconversion or four-fold increase of Zika-specific antibodies in paired samples. However, Dr. St. John warned that “Due to the possibility of cross reactivity with other viruses, for example, dengue, it is strongly recommended samples be collected early enough for PCR testing.”

Zika and pregnancy

Zika virus has now been identified in 14 countries and territories worldwide, and while most infected patients experience relatively mild symptoms, Zika becomes very concerning when it infects a pregnant woman, as there have been cases of microcephaly in children whose mothers were infected with Zika virus during pregnancy. Although the association of microcephaly with Zika virus infection during pregnancy has not been definitively confirmed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have already issued a warning to Americans – particularly pregnant women – about traveling to high-risk areas.

“Scientifically, we’re not 100% sure if Zika virus is causing microcephaly, [but] what we’re seeing is in certain Brazilian districts, there’s been a 20-fold increase in rates of microcephaly at the same time that there’s been a lot more Zika virus in pregnant women,” explained Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake of Australian National University in Canberra.

According to data from the CDC, 1,248 suspected cases of microcephaly had been reported in Brazil as of Nov. 28, 2015, compared to the annual rate of just 150-200 such cases during 2010-2014. “Examination of the fetus [and] amniotic fluid, in some cases, has shown Zika virus, so there seems to be an association,” Dr. Senanayake clarified, adding that “the [ ANVISA – Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency] has told women in certain districts where there’s been a lot of microcephaly not to get pregnant.”

Brazil is set to host millions of guests from around the world as the 2016 Olympics get underway in only a few months’ time. Women who are pregnant or anticipate becoming pregnant should consider the risks if they are planning to travel to Rio de Janeiro. The risk of microcephaly does not apply to infected women who are not pregnant, however, as the CDC states that “Zika virus usually remains in the blood of an infected person for only a few days to a week,” and therefore “does not pose a risk of birth defects for future pregnancies.”

Dr. St. Joy also stated that “public health personnel are still cautioning pregnant women to take special care to avoid mosquito bites during their pregnancies,” adding that the “[Pan-American Health Organization] is working on their guidelines for surveillance of congenital abnormalities.”

Clinical insights

With treatment options so sparse – there is no vaccine or drug available specifically meant to combat a Zika virus infection – what can healthcare providers do for their patients? The CDC advises health care providers to “treat the symptoms,” which means telling patients to stay in bed, stay hydrated, and, most importantly, stay away from aspirins and NSAIDs “until dengue can be ruled out to reduce the risk of hemorrhage.” Acetaminophen or paracetamol are safe to use, in order to mitigate fever symptoms.

Those who are infected are also advised to stay indoors and remain as isolated as possible for at least a week after symptoms first present. While the risk of a domestic outbreak is probably low, Dr. St. John said, the more exposure a Zika virus–infected individual has to the outside world, the more likely they are to be bitten by another mosquito, which can then carry and transmit the virus to another person.

“Chikungunya and dengue virus, which are transmitted by the same vectors [as Zika virus], have not managed to establish ongoing transmission in the U.S. despite repeated importations, [so] it is likely that Zika virus’ spread would follow a similar pattern,” Dr. St. John noted.

Though rare, sexual transmission of Zika virus has also been found in at least one case , although it had been previously suspected for some time. In December 2013, a 44 year-old Tahitian man sought treatment for hematospermia. Analysis of his sperm, however, found Zika virus, indicated possible sexual transmission of the virus.

“The observation that [Zika virus] RNA was detectable in urine after viremia clearance in blood suggests that, as found for [dengue] and [West Nile virus] infections, urine samples can yield evidence of [Zika virus] for late diagnosis, but more investigation is needed,” the study concluded.

“The best way to control all this is to control the mosquito,” said Dr. Senanayake. “You get a four-for-one deal; not only do you get rid of Zika virus, but also chikungunya, dengue, and yellow fever.” Dr. Senanayake added that advanced research is currently underway in mosquito control efforts, including the idea of releasing mosquitoes into the wild which have been genetically modified so they can’t breed.

Now that the Illinois Department of Health has confirmed two new cases of Zika virus infection in that state, with other new cases cropping up in Saint Martin, Guadeloupe and El Salvador , providers should remain vigilant, taking note of patients who have traveled to afflicted regions and show mosquito bites. Person-to-person transmission is “rare as hen’s teeth,” said Dr. Senanayake, which is to say, it is highly unlikely to occur. Nonetheless, he said information and communication is the best way to ensure that Zika virus does not spread widely in the United States.