The core of pharmaceutical marketing has expanded from efficacy and safety to include value. Often, value is conflated with price, especially by payer organizations. Value encompasses more than just prices: It also includes the measurable health improvement that the patient receives. Value can be assessed through pharmacoeconomics, using metrics like quality-adjusted life years that allow products to be benchmarked against competitors or to quantify how much value a product delivers.

In pharmaceutical marketing, we are commonly tasked with communicating this value, typically by creating a value proposition. The purpose of the value proposition is to both differentiate a product and to justify the price paid in terms of benefit provided, or value received. Often, a newly launched product will be priced at a premium compared with existing products. This situation frequently requires us to review the disease burden, unmet needs, product claims and clinical data, and ideally, economic justification for covering the new product. Unfortunately, the regulatory restrictions of the pharmaceutical industry that limit product claims to the prescribing information, rarely make the value proposition compelling.

How has the importance placed on value changed?

In the past, a drug’s value only had to be communicated to the prescribers, who were most interested in efficacy and safety. Value, in terms of justifying cost, only came up in therapeutic areas in which the products were relatively interchangeable and competitors made the price difference a selling point, or when products were prohibitively expensive.

But if providers’ desire to use a product were great enough, then most payers (insurers, including government payers like the VA, Department of Defense (DoD), Medicare, and Medicaid) would make the product available. A news report featuring a patient denied a potentially life-saving (or life-extending) drug by their insurer was feared by payers and led to a hands-off policy for most orphan drugs and cancer treatments. Today, “protected classes” of drugs are included under Medicare, such as cancer drugs, that ensure payers cannot exclude them.

The Downside of Confusing Cost with Value

In the past, prescribers rarely knew actual drug costs. Patients would only complain of cost if the copayment was high or if the drug was rejected for coverage altogether. It is not clear that prescribers know drug costs now, but they are largely aware of patient out-of-pocket costs, at least for commonly prescribed medications.

Payers often look at pharmacy costs, but not the product’s ability to reduce other costs of care (i.e., medical cost offsets). Even now, budgets for pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient costs are typically siloed. Medicare is divided into Part A (hospitalization), Part B (outpatient care), Part C (Medicare Advantage, which is a private part B, with or without Part D included), and Part D (third-party prescription drug coverage). Similarly, most commercial insurance plans are divided into pharmacy benefit, medical benefit, and major medical (hospitalization) benefit. Commercial plans may utilize a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) to manage the pharmacy benefit.

These separations may functionally prevent savings in other care categories from being realized by firewalled budgets. A PBM or Medicare Part D plan has no incentive to offset other costs (including those for hospitalization or even long-term care) by increasing their drug spending. Although the need to assess the impact of costs across sites of care delivery has increased, the reality of meaningful value assessment across these silos remains unrealized.

What has changed in the pharmaceutical market?

Over the past few years, the following seven changes have occurred in the industry and ultimately influenced how pharma companies must now determine value.

1. Institutional/Organizational Influences

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicare Part D, significant payer and PBM consolidation, and major shifts in plan design are some of the key changes that have influenced how the pharmaceutical marketplace reckons with cost.

The ACA has expanded access to more patients through health insurance exchanges and through Medicaid expansion (in states that allowed for it). The plans offered to these patients typically have limited pharmacy benefit offerings, compared with employer-provided commercial plans. Along with some of the low-cost plans in Medicare Part D, many of these plans provide narrow coverage, with many drug exclusions and a strong emphasis on generics, which now account for nearly 90% of all prescriptions.

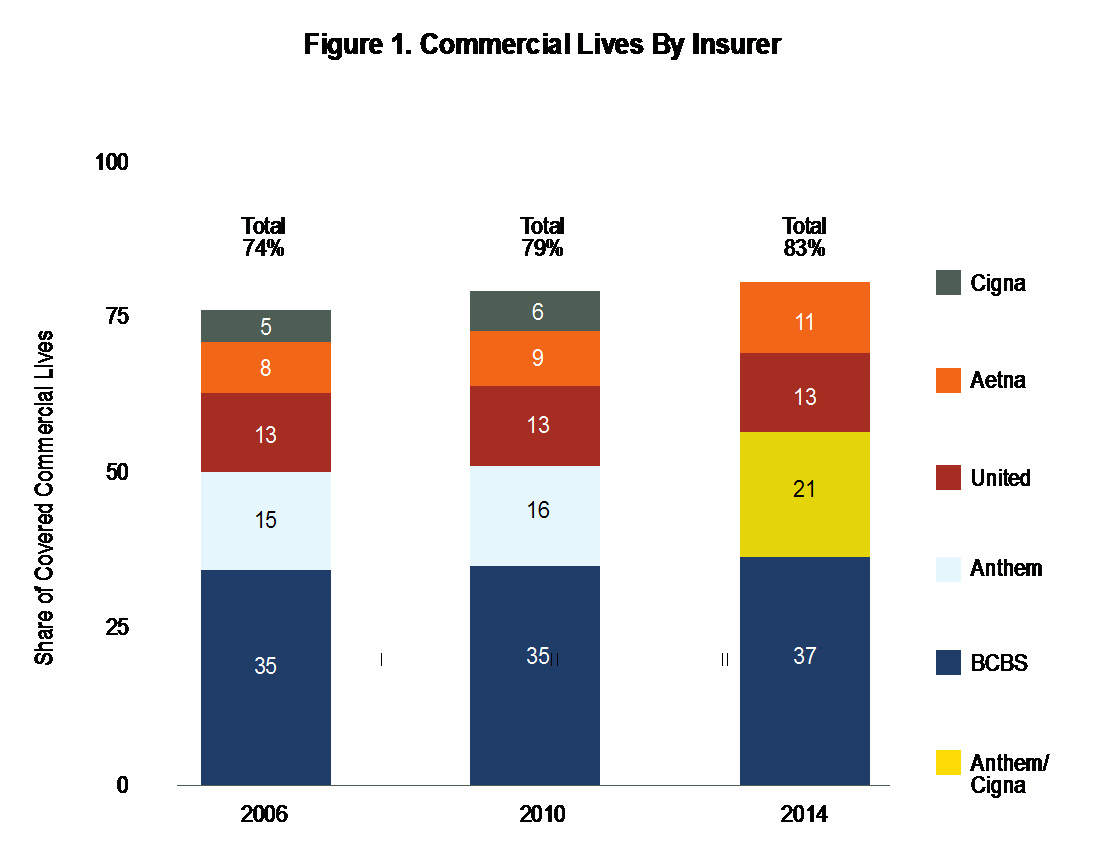

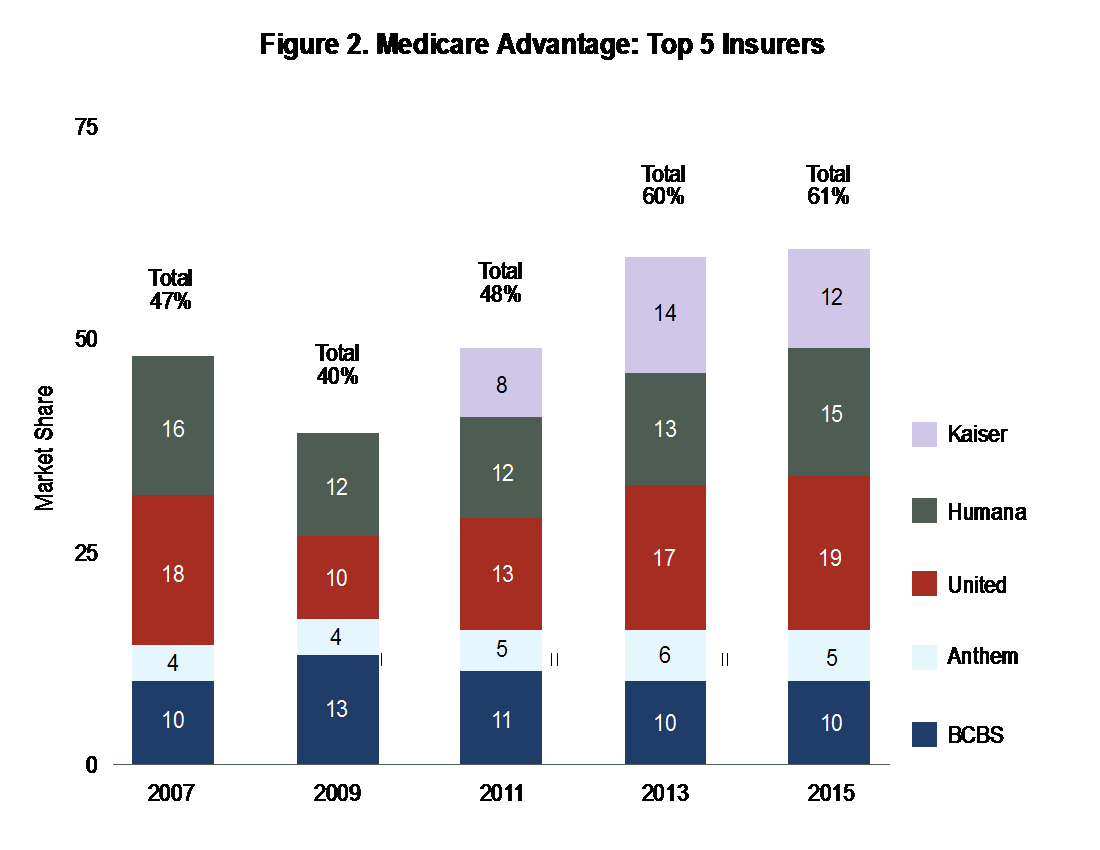

Payer consolidation has continued as well: The Commonwealth Fund reports that four commercial payers controlled 83% of the market in 2014, and four Medicare Advantage providers controlled 61% of the market in 2015.1

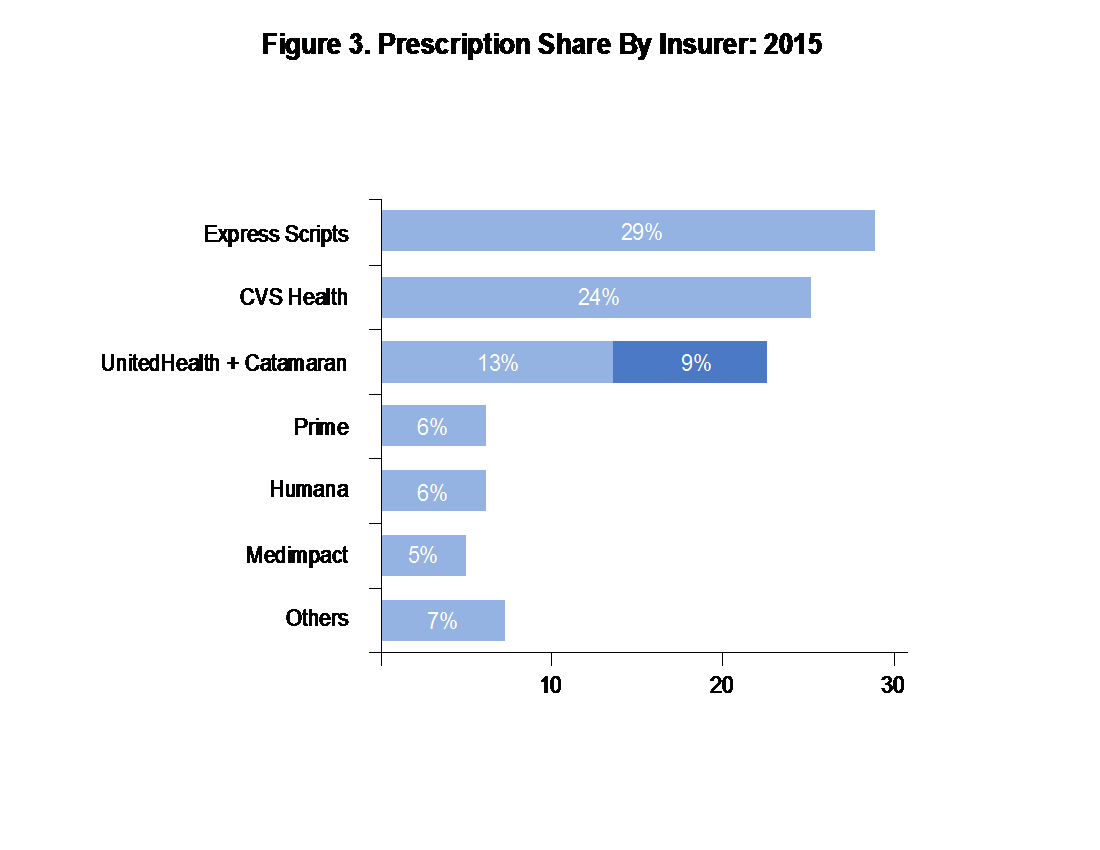

PBMs have also undergone consolidation: Forbes published that the top four PBMs control 81% of prescription share (see Figure 3).2

Plans have, in turn, adopted multiple strategies to rein in healthcare costs including greater patient cost sharing (with the stated intention of making patients more cost aware), expansion of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs), higher copayment/coinsurance requirements, and an increase in the number of drug tiers from a typical three-tier system (generic/preferred/nonpreferred) to more elaborate tier arrangements that may include split levels of generic tiers and one or more specialty tiers. Some tiers may not have fixed copayments, instead using a percentage coinsurance driven by cost. Typically, the threshold for a drug to end up in a specialty tier is a monthly cost of $600 monthly (rising drug price may raise this threshold to $650).

2. Shifts in Pharmaceutical Product Introductions

Some of the external changes have happened independently, while others have been in direct response to product changes in the marketplace.

3. Pharmaceutical Pricing Practices

A number of events have changed how pharmaceutical companies price their products—new products, new marketing practices, and the rise of generics among them. The level of concern over these circumstances is evidenced by extensive media focus and the fact that leading candidates in both political parties have mentioned the issue, as well as several ongoing congressional (and in some cases criminal) investigations.

4. Pricing Relative to Overall Healthcare Costs

According to the May 2015 issue of the Milliman Medical Index, “Prescription drugs have increased by 9.4% on average, exceeding the 7.7% average trend for all other services.”3 IMS Health has reported that drug spending grew 12.2% in 2015, down from 14.2% growth in 2014. IMS Health also reported that net prices for branded drugs rose 2.8% in 2015, versus a 12.4% rise in wholesale prices last year. This shift indicates that marketplace dynamics are changing, and contracting is moderating the impact of price increases.4

5. Pricing and Shortages of Generics, Especially Injectables

Even generics have created pricing and availability crises. In recent years, prices have increased sharply for generics, some of which have been in use for 50 years or more. The Wall Street Journal reported the cost of generics going up 37% in one quarter in 2015. Multiple causes have been identified.5 In some cases the prices of the products had declined to a point in which manufacturers abandoned them; in others, industry consolidation eliminated competitors, and in others (especially injectables), FDA good manufacturing practices violations reduced availability. At the point where demand exceeded supply, the price skyrockets. Examples of limited availability affecting price include colchicine for gout (50-fold), digoxin for heart failure (6-fold), and isoproterenol for heart rhythm abnormalities (5-fold).

6. Price Increases for Branded Products Have Been Substantial

Substantial price increases for existing medications have sensitized payers to pharmaceutical costs, especially because medical cost increases have been relatively low. Reuters, in a report reviewing IMS Health data, cited prices of four of the top 10 drugs more than doubled in price since 2011. The remaining six increased more than 50%. This reflects higher relative spending increase on drugs versus doctor visits and hospitalizations seen over the last five years.6

Oncology products, in particular, have been a focus—regulations compel payers to cover oncology drugs as protected classes under Medicare Part D. Many of the new oral oncology agents are taken for long periods of time, and some may be used indefinitely. The costs of new oncology agents may exceed $10,000 per month. The most common technique for managing costs of oncology products is to require prior authorization to confirm indication and utilize National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for appropriateness of use. Some payers negotiate with oncology providers to treat along predetermined pathways proposed by the oncology group, defined by a third party like NCCN, or defined by a commercial organization, such as P4 Healthcare.

Drug prices have become such a great concern that the American Society of Clinical Oncologists (ASCO) has taken the position that oncologists should consider drug costs as part of the treatment decision: “Since 1965 when Medicare was created, the introductory cost of new cancer drugs has increased 100-fold to approximately $10,000 a month (adjusted to 2014 dollars). Older drugs also contribute to soaring costs; the price of imatinib has risen from less than $100 per day in 2004 to more than $200 in 2014.”7

Specialty drugs have also risen at rates that far surpass payer expectations. The costs of multiple sclerosis treatments were addressed in a study published last year in Neurology: “First-generation DMTs, originally costing $8,000 to $11,000, now cost about $60,000 per year. Costs for these agents have increased annually at rates five to seven times higher than prescription drug inflation. Newer DMTs commonly entered the market with a cost 25%–60% higher than existing DMTs.”8

7. Players Being Perceived as Opportunistic, Making Pricing Seem Arbitrary

As noted by the editorial board of the New York Times: “There is ample evidence that drug prices have been pushed to astronomical heights for no reason other than the desire of drug makers to maximize profits.”9

Martin Shkreli, former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, became the poster boy for predatory pricing after he raised the price of a decades-old antiparasitic agent used in HIV and cancer by 5,556%, and then offered a justification that sounded more like Wall Street arbitrage than healthcare marketing. The magnitude of the price increase appeared to result in greater scrutiny of other companies that used similar strategies of eliminating research and development (R&D), followed by acquisitions and then price increases.

Mallinckrodt was the subject of some additional scrutiny after acquiring Acthar Gel from Questcor Pharmaceuticals. According to Bloomberg: “H.P. Acthar Gel, extracted from the pituitary glands of pigs and used for patients with lupus, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions, rose from $1,235 a vial in 2005 to $29,086 a vial in 2008, according to Red Book, a directory of drug prices. The increase caused an uproar, long before such price hikes became so common that they’re now an issue in the presidential campaign. A vial now costs about $35,000, according to price comparison site GoodRx.”10

Valeant Pharmaceuticals had a corporate strategy of low R&D coupled with an acquisition and price increase model, and it excelled for a number of years with this model. However, as a result of practices that are being questioned in specialty pharmacy, coupled with dubious accounting practices, the company has stumbled of late, with stock price falling 90%, changes in the boardroom, and congressional inquiries.

Gilead, AbbVie, and others making newer, efficacious hepatitis C treatments have come under fire: The Gilead products for hepatitis C (Sovaldi and Harvoni) cost $1,000 per day, with most patients requiring the product for 12 weeks ($84,000) but a minority requiring it for 24 weeks ($168,000). Although these treatments are an effective cure for patients who could otherwise develop severe liver disease or liver cancer, the payers most affected by this product were State Medicaid and other government payers, many of which are already underfunded. Patients often have this virus as a chronic infection that does not exhibit symptoms for two or three decades. The result, in this case, was that some payers delayed treatment in patients without significant liver damage while awaiting additional new drugs to drive more competitive pricing.

What are payers currently focusing on?

Because overall healthcare costs are growing by single-digit percentages, the price increases in pharmaceuticals stand out, and payers are now focusing heavily on pharmaceutical costs. The siloed approach to managing healthcare delivery, separating pharmaceutical coverage from other outpatient care, creates a situation in which the medical cost offsets remain harder to leverage, and price takes precedence over value.

The Urgent Need for Pharma to Establish Value—But the Danger in Doing So

Pharma has been conservative about comparative effectiveness research, for good reason. Market research with prescribers and payers asking what they would like from pharmaceutical companies to support their products is almost always led by head-to-head studies with whatever the standard of care might be. Pivotal trials used to gain approval, however, might allow comparison with placebo to demonstrate effectiveness, or might be noninferiority studies, in which the goal is to show that the new product is no worse than the comparator. Such studies result in more limited labels for the products, but can speed up time to market and have lower risk of failure.

Case in point: Bristol-Myers Squibb funded a study comparing its cholesterol drug Pravachol with Pfizer’s Lipitor. The study found that those taking Pravachol experienced a slow progression of atherosclerosis over 18 months, but those who took the highest dose of Lipitor experienced a cessation of disease progression. After publication of the results, sales of Pravachol fell, and Lipitor became the sales leader for the next decade. Thus, the road to proving a product’s value can be a treacherous one.

Racing to Define Value

Organizations are rushing to establish themselves as the experts who will assign value to treatments. In oncology, the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s value framework and the NCCN’s value pathways have merged as leaders in establishing value.

Cancer centers have become involved as well. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center’s Center for Health Policy and Outcomes developed DrugAbacus, an evidence-based drug-pricing project aimed at analyzing the value of the new generation of cancer drugs.

The danger to pharma is that these organizations have their own agendas. For example, oncology groups may believe that expensive drugs make less money available for providers, leading to a greater focus on the value of the provider in treatment.

How should pharma move forward on value?

Without a change in how drug value is communicated, there is growing danger that products will be managed almost completely by price.

The most obvious need is data: Superiority commands a price premium. Some options for gleaning new data include the following:

- Mining the clinical data for gems—identifying what insights are most meaningful for payers.

- Identifying follow-up research to gain a marketing edge, from gross advantage to segment niche.

The industry also needs more and better communication of products’ value propositions.

- Product differentiation is more critical than ever. From a marketing perspective, “different is as good as better.”

- Companies need to identify and clearly communicate product features and the benefits that affect payers, providers, and patients. (The messaging, while it should be consistent, may not be the same for each audience.)

- The industry also needs to invest in the movement toward value-based medicine. For instance, although PBMs will not pay for value up front, once a product’s value has been established with payers, PBMs will likely follow suit.

- Contracting innovations are another area for exploration. Risk sharing, outcomes-based contracting, and other strategies are still beyond the abilities of many organizations, but the market is changing. Data integration is increasing all the time, and big data remains a promising way to identify high-risk/high-cost patients.

- Pull-through excellence is another necessity. Contracts can become money losers if the access purchased does not turn into market share that delivers return on contracting investment.

The challenges facing pharma are substantial, the central issue is how to maximize returns for investors by optimizing product revenue without triggering market controls that would limit access and usage. The winners will be those whose differentiated value propositions result in positive customer perceptions.

References:

1. “Evaluating the Impact of Health Insurance Industry Consolidation: Learning from Experience.” http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/nov/evaluating-insurance-industry-consolidation. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.

2. “Insurance Companies Start To Bring PBM In-house: CVS Health’s PBM Business Could Be Under Threat.” http://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2015/07/28/insurance-companies-start-to-bring-pbm-in-house-cvs-healths-pbm-business-could-be-under-threat/#1863e7b73df2. Updated July 28, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.

3. 2015 Milliman Medical Index. http://us.milliman.com/uploadedFiles/insight/Periodicals/mmi/2015-MMI.pdf. Updated May 19, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.

4. “U.S. Prescription Drug Spending Rose 12.2 percent in 2015.” http://www.firstwordpharma.com/node/1374488#axzz45oGsWwUC. Updated April 14, 2016. Accessed June 16, 2016.

5. “Feds to Probe Impact of Generic Drug Price Increases on Medicaid.” http://blogs.wsj.com/pharmalot/2015/04/14/feds-to-probe-impact-of-price-increases-of-generic-drugs-on-medicaid/. Updated April 14, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.

6. “Exclusive: Makers Took Big Price Increases on Widely Used U.S. Drugs.” https://www.yahoo.com/news/exclusive-makers-took-big-price-increases-widely-used-100704229–finance.html. Updated April 4, 2016. Accessed June 16, 2016.

7. “Cost of Cancer Drugs Should Be Part of Treatment Decisions.” http://am.asco.org/cost-cancer-drugs-should-be-part-treatment-decisions. Updated May 31, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.

8. Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. “The Cost of Multiple Sclerosis Drugs in the U.S. and the Pharmaceutical Industry: Too Big to Fail?” Neurology. 2015;84(21):2185-2192.

9. “No Justification for High Drug Prices.” http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/20/opinion/sunday/no-justification-for-high-drug-prices.html?_r=1. Updated December 19, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.

10. “Mallinckrodt’s $35,000 Drug Is Back in the Spotlight.” http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-09/with-citron-tweet-mallinckrodt-s-35-000-drug-back-in-spotlight. Updated November 9, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2016.