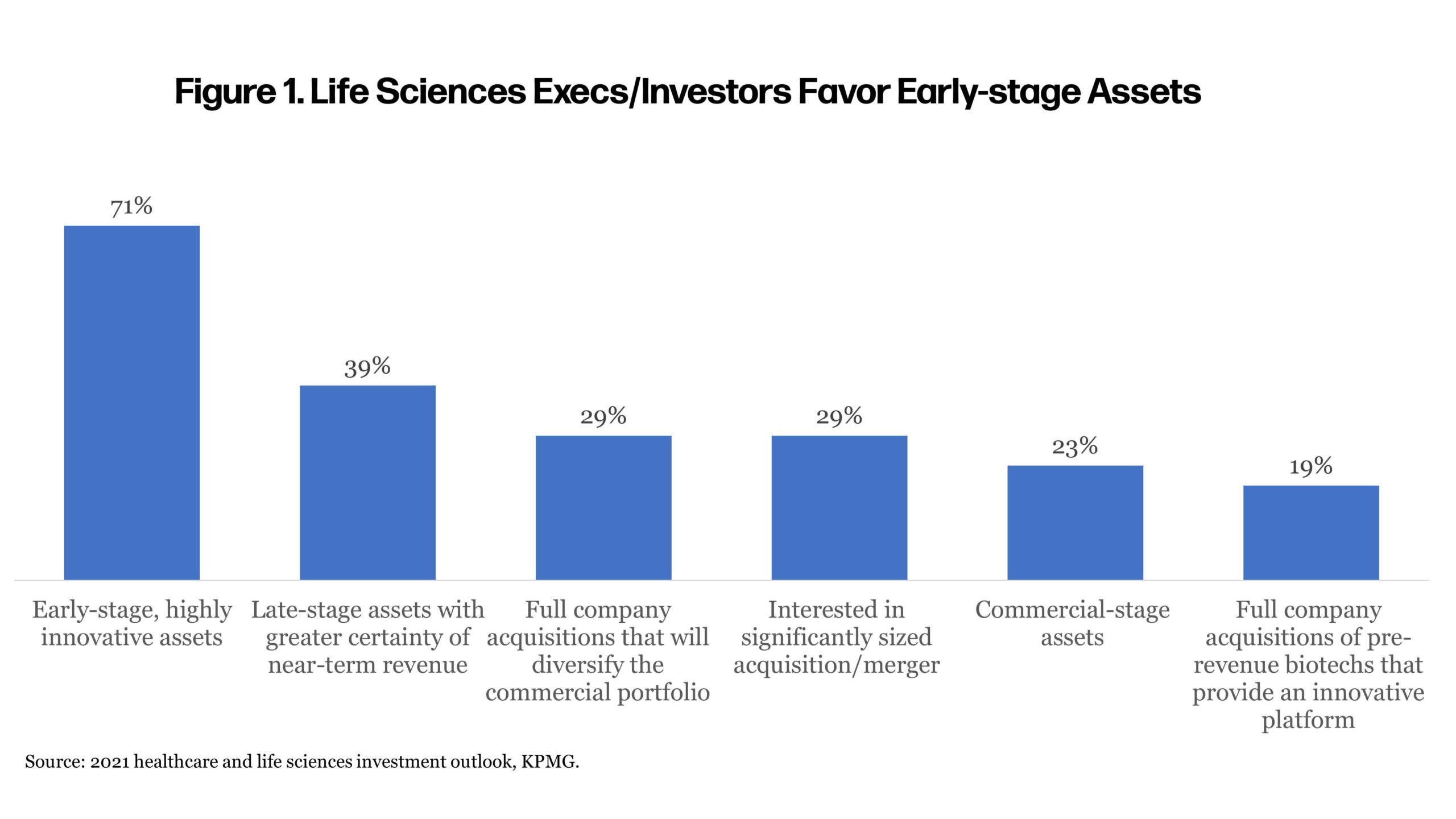

Biotech companies are soaring in a low-interest-rate climate, and the promise of emerging technologies to treat disease are attracting an assortment of investors to fund early-stage, biotech companies that may be years away from seeing revenue. Many biotech companies are offering promising technologies to treat disease or give scientists the tools to advance knowledge of genetics, biochemistry, disease paths, or new drug development. The trend toward early-stage investment was evident late last year. KPMG’s survey of healthcare and life sciences executives and investors found that 71% of pharma executives (Figure 1) intended to acquire early clinical-stage pipeline assets, but how these companies are funded and how pharma can now approach investments has changed.

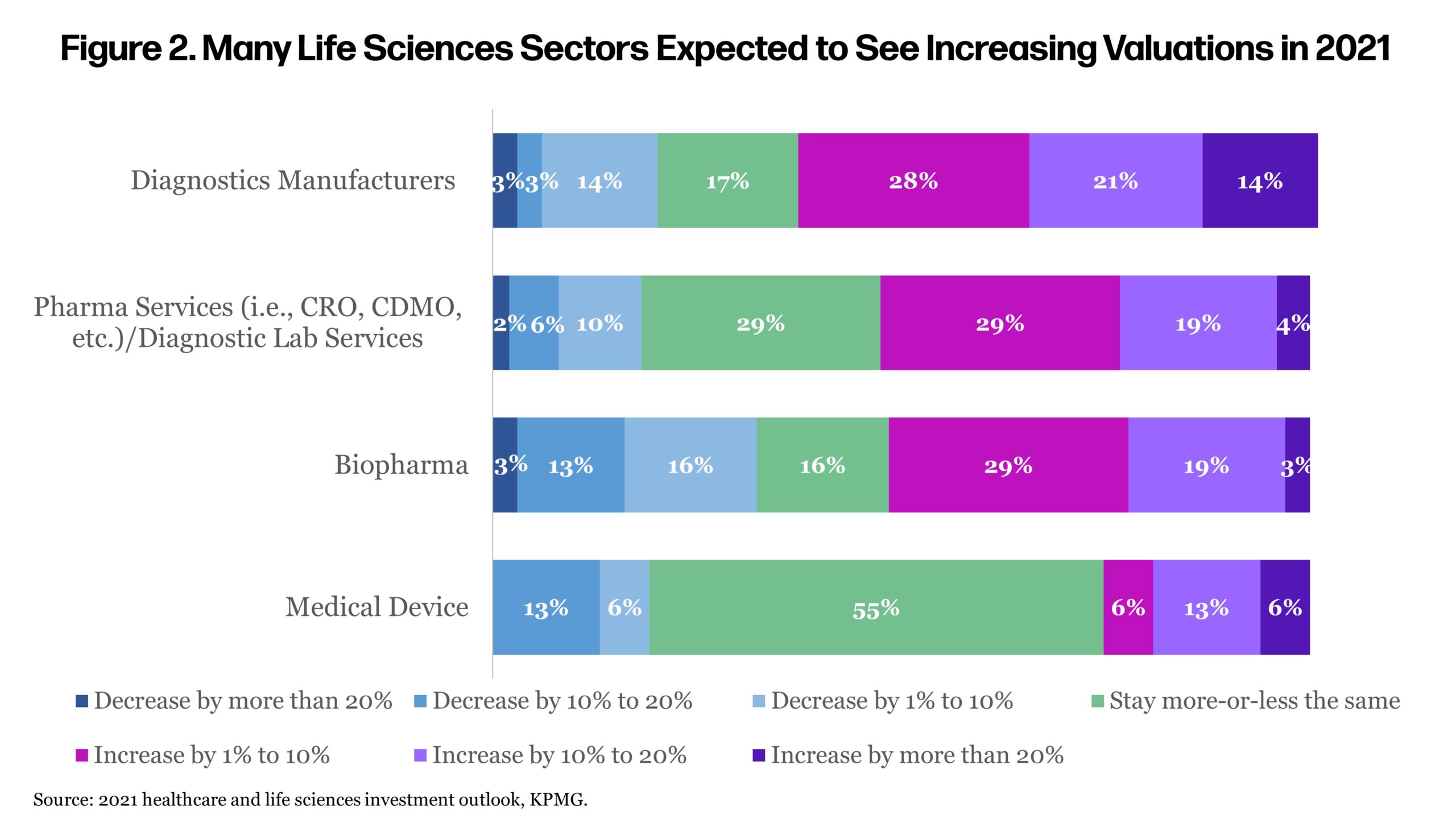

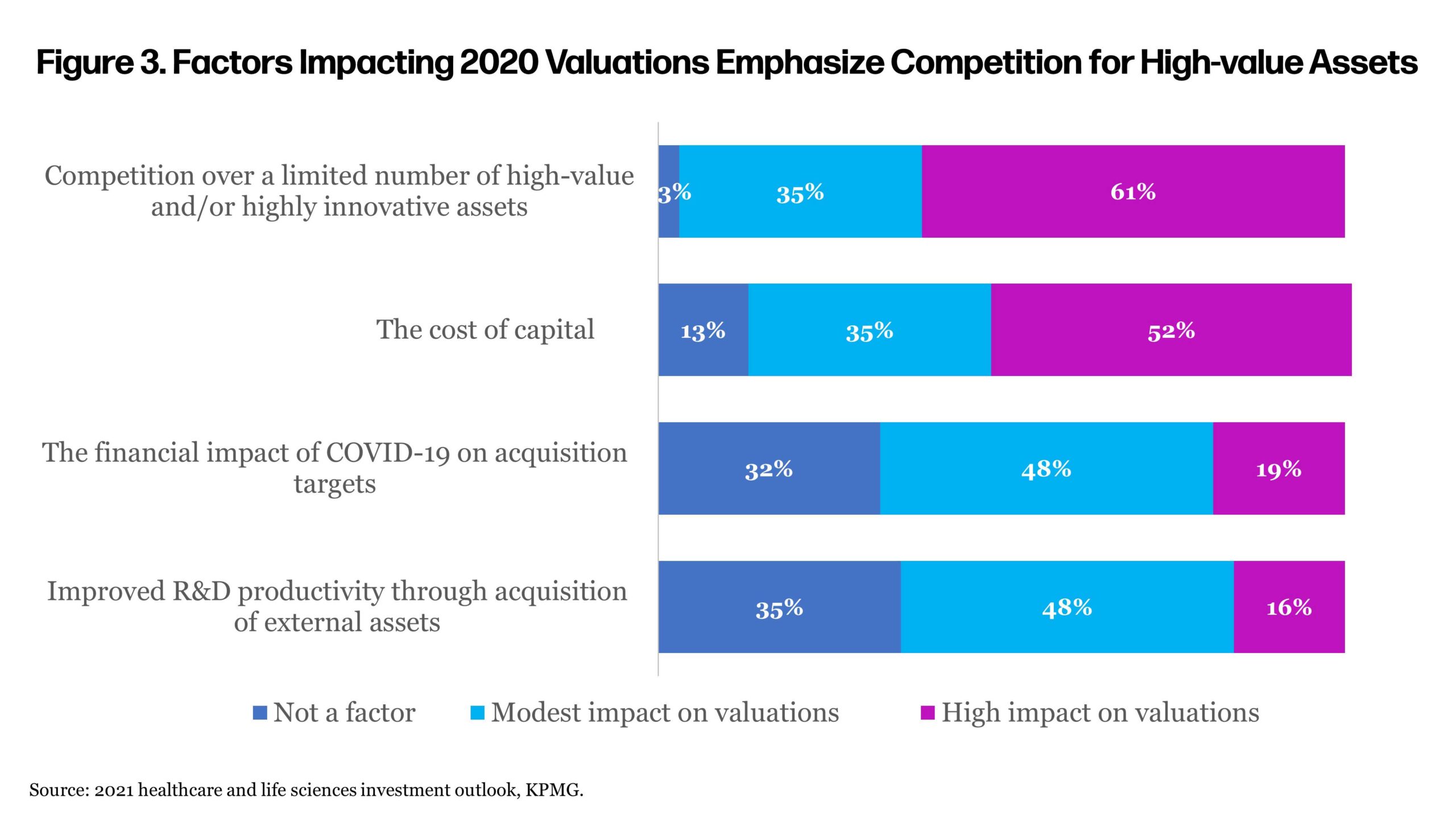

Many executives in the survey anticipated rising valuations of biopharma companies this year (Figure 2). Competition for these assets is seen as driving up values (Figure 3). In the heated investment climate, history has shown biotech investment to be very cyclical, where promising clinical developments can spur exuberance while setbacks can sometimes lead to pessimism.

Many executives in the survey anticipated rising valuations of biopharma companies this year (Figure 2). Competition for these assets is seen as driving up values (Figure 3). In the heated investment climate, history has shown biotech investment to be very cyclical, where promising clinical developments can spur exuberance while setbacks can sometimes lead to pessimism.

Reflecting this volatility in the sector, the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index’s annual returns since 1994 range from negative 45.33% (2002) to positive 101.64% (1999) and had negative returns as recently as 2016 and 2018.1 Volatility in the returns, contrasted with some of the big pharma names in the index, illustrate how potential gains and losses can be amplified for early-stage investors.

Reflecting this volatility in the sector, the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index’s annual returns since 1994 range from negative 45.33% (2002) to positive 101.64% (1999) and had negative returns as recently as 2016 and 2018.1 Volatility in the returns, contrasted with some of the big pharma names in the index, illustrate how potential gains and losses can be amplified for early-stage investors.

Venture capital, angel investors, and research grants have traditionally been the key funding sources for pre-IND to Phase I biotech companies, given the fact that drug development burns through cash during clinical trials, which requires a great deal of patience. Venture capital companies take a different approach to risk by spreading investments across a variety of early-stage companies with the hope that the success of a few investments will offset the failures.

Venture capital, angel investors, and research grants have traditionally been the key funding sources for pre-IND to Phase I biotech companies, given the fact that drug development burns through cash during clinical trials, which requires a great deal of patience. Venture capital companies take a different approach to risk by spreading investments across a variety of early-stage companies with the hope that the success of a few investments will offset the failures.

Strategic partners from the pharma sector sometimes help with funding through licensing and research agreements for more promising candidates. About a decade ago, most of the investment from big pharma was focused on companies with compounds in the latter stages of clinical trials, which have a greater likelihood to bring a product to market; however, in recent years large pharmaceutical and biotech companies have invested larger sums of capital to pre-clinical and Phase I stage companies.

A Crash Course in SPACs

Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) have changed fundraising dynamics in life sciences and have shown themselves as capable suitors to take these companies public. SPACs are “shell companies” or “blank check companies” with one purpose: acquiring an operating company that will function as a publicly traded business.

After a SPAC raises money from selling its stock in an initial public offering (IPO), net proceeds are held in a trust account until a transaction is completed or the funds are returned to investors if a transaction is not completed within a set timeframe. Once the SPAC has identified an initial business combination opportunity, its management negotiates with the operating company and, if approved by SPAC shareholders (if a shareholder vote is required), executes the business combination. This transaction is often structured as a reverse merger in which the operating company merges with and into the SPAC or a subsidiary of the SPAC.

Whether SPAC investment remains strong through the year remains to be seen, but for now it does offer some advantages for investment in life sciences and other sectors. The growth of SPACs has changed the dynamic of capital raising, accounting for more than half of the listings during 2020, according to Nasdaq.2 Developments in molecular biology and genetics, as well as the response to COVID-19, have cast a favorable light on drug and vaccine makers that are creating new opportunities to treat disease, making them a hot sector for SPACs to go shopping.

SPACs can offer a shortcut for biotech companies, taking them public quickly and often sparing them from additional rounds of fundraising—plus it gives them the opportunity to control more of their own destiny. Instead of developing a strategic partnership with a larger pharmaceutical company and co-developing a product’s clinical development strategy, the funding windfall from a successful SPAC can create enough capital to take an asset from Phase I through Phase III.

However, the blank check has a lot of power and can be a compelling option for a company to focus on research and bringing a compound to the market. A SPAC can take the company public considerably faster—five to eight months—rather than a traditional IPO underwriting process, which can be as long as a year. The hard work of underwriting among the investment banks to build investor interest and help the market set a value for the company can also be upended by trading volatility in which a bad day in the stock market can disrupt the timing and the total proceeds to a company.

A Question of Maturity

While taking the SPAC route offers some advantages, the problem is not every development-stage company is ready to go public. Some organizations might be too dependent on the clinical success of one asset that is too far away from being commercially viable or the management team is not ready to deal with the regulatory and market demands of having publicly traded stock. Management teams of early-stage companies that have a strong history of either developing investment from larger biopharmaceutical companies or from investors across multiple assets typically have a stronger chance of being successful in public markets.

From a scientific standpoint, developing a new drug is rarely a straight-line march through clinical trials to approval. Even products that are successful sometimes stumble in clinical trials when endpoints are not met. Safety issues may emerge and time is spent determining whether the compound being studied caused it.

Hurdles also emerge after approval, such as manufacturers addressing competition to target specific disease states as well as the challenges of negotiating terms with payers about how they’ll cover a treatment.

Any of the hurdles involved in the process of getting a medication to market could be disruptive to the share prices of even the most established drugmakers. So when it comes to a pre-revenue drugmaker, you can imagine that the volatility is only amplified and the company’s value is further diminished.

Most recently, government action has created questions about SPAC deals and the market has cooled somewhat. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has issued investor bulletins tied to SPACs, stating, “With an increasing number of SPACs seeking to acquire operating businesses, it is important to consider whether attractive initial business combinations will become scarcer.”3

The SEC’s other big concerns are centered on SPAC sponsors getting more favorable terms over public investors and about potential conflicts of interest among insiders. Since a new SPAC does not have an operating history to evaluate, investors need to review the business background of SPAC management and its sponsors.

Can SPACs Be Successful in Life Sciences?

A number of SPACs are focusing specifically on the life sciences sector and have built teams that understand the science or potential clinical benefits tied to products under development. Biotech firms seem well positioned to continue leveraging SPAC transactions over the longer term. In an examination of the financial and marketplace factors—including an appetite for risk in a low-interest rate environment—SPACs have become more prominent. It was not always that way.

In the past, a biotech merging with a shell company or SPAC was often looked askance by some investors because underwriting is a consensus building and vetting process in the market. In the case of a SPAC, the team looking for the acquisitions serves as the vetting process and the hope is that they have the scientific and business backgrounds to find successful early-stage biotechs. While there is a two-year time window for a SPAC to complete deals, having a management team that is willing to walk away from a deal where valuations get too rich could be as important as picking the right investment.

While SPACs could have governance issues much like other companies, their success or failure will depend largely upon:

- Good Science: Not all early-stage programs are created equal. Some companies enter Phase I with extensive academic and translational science demonstrating the biological foundations of the mechanisms of action and its association with the disease pathogenesis. Others, unfortunately, are much more speculative.

- Clinical Strategy: Once medicines move from animal models to the clinic, the team running studies need to keep an eye balancing the necessary information for regulatory and commercial success and running efficient clinical trial programs that are compelling to investor timelines. This can be challenging for companies bringing innovative products into disease areas that lack standardized and validated endpoints.

- Management Quality: Drug development is expensive and there is a reason why the investment community examines “cash burn” and the need for successive fundraising. Successful operators can address the clinical and scientific needs of getting a compound through trials while addressing the legal, financial, and operational functions of the business.

Whether SPACs will have staying power remains to be seen, but they have created more flexible alternatives for early biotechs to allow them to create the medicines of the future.

References:

1. http://www.1stock1.com/1stock1_791.htm.

2. https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/a-record-pace-for-ipos-2021-01-14.