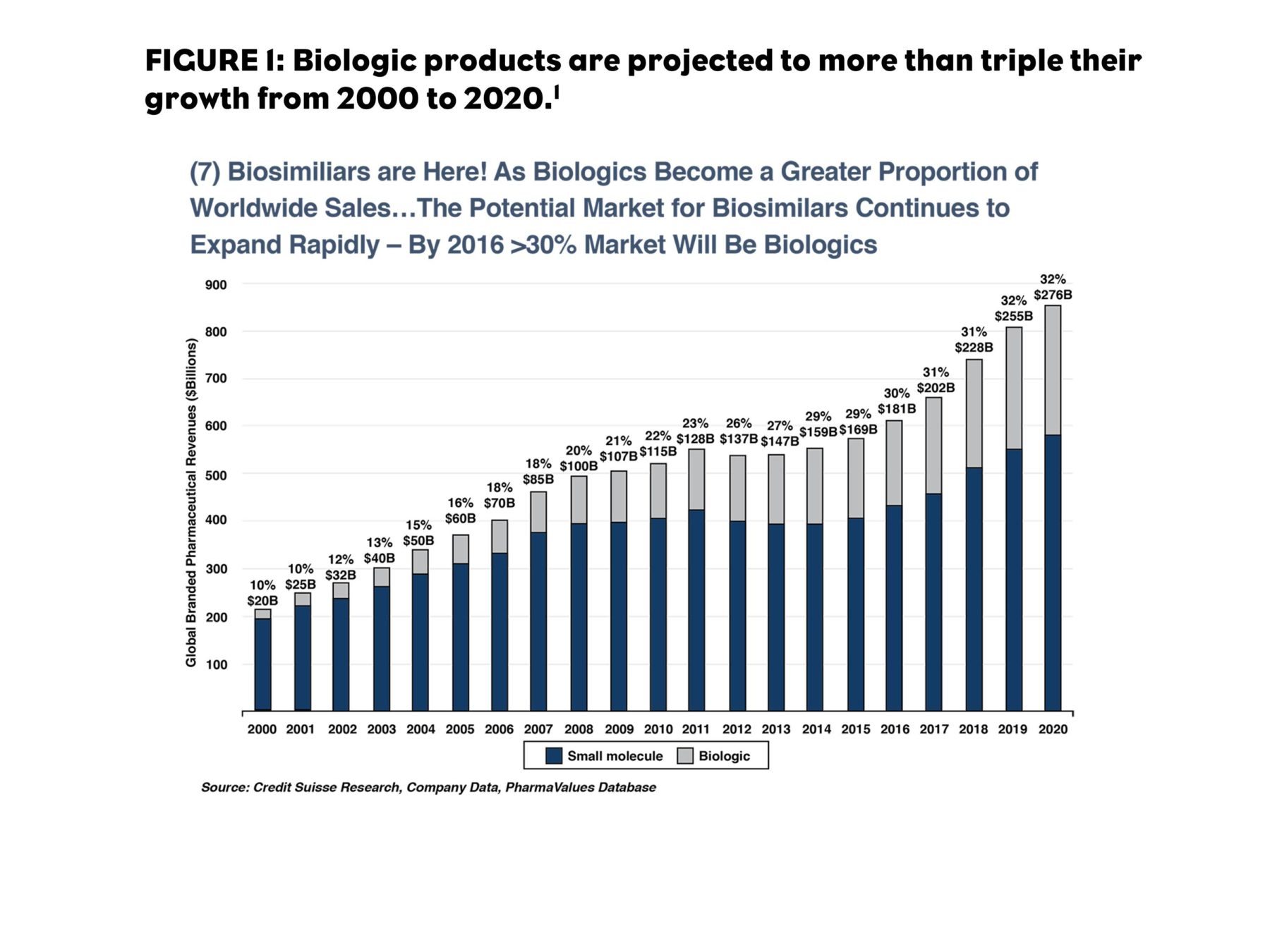

The number of biologics available in the U.S. has grown every year for the last 17 years, making biologics a large part of the pharmaceutical marketplace.1 By 2020, they are expected to account for one-third of all global pharmaceutical revenue. The therapeutic areas that are most affected by biologics include diseases for which there are few effective traditional therapies.

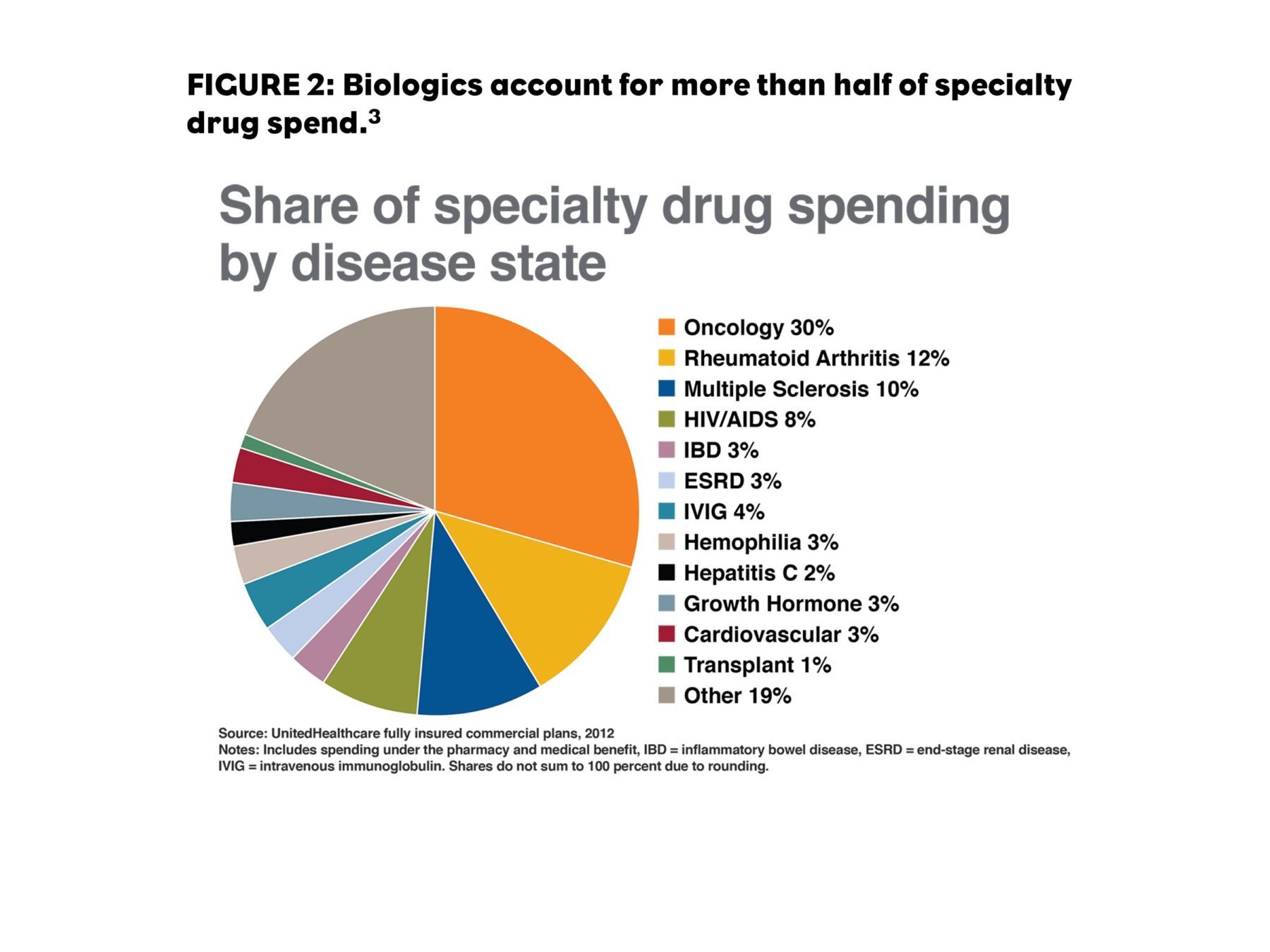

Specialty pharmacy sales are expected to reach 50% of pharmacy spend as early as 2018.2 Although the pharmaceutical marketplace is now dominated by generics in the U.S., with generic products representing nearly 90% of prescriptions filled, branded pharmaceutical revenues continue to climb because of the shift from high-volume primary care products to high-cost specialty products. Biologics are a large part of the specialty category, making up more than half of all treatments for biologic agents for oncology, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and multiple sclerosis (MS).

The Opportunity for Biologics will Expand Significantly

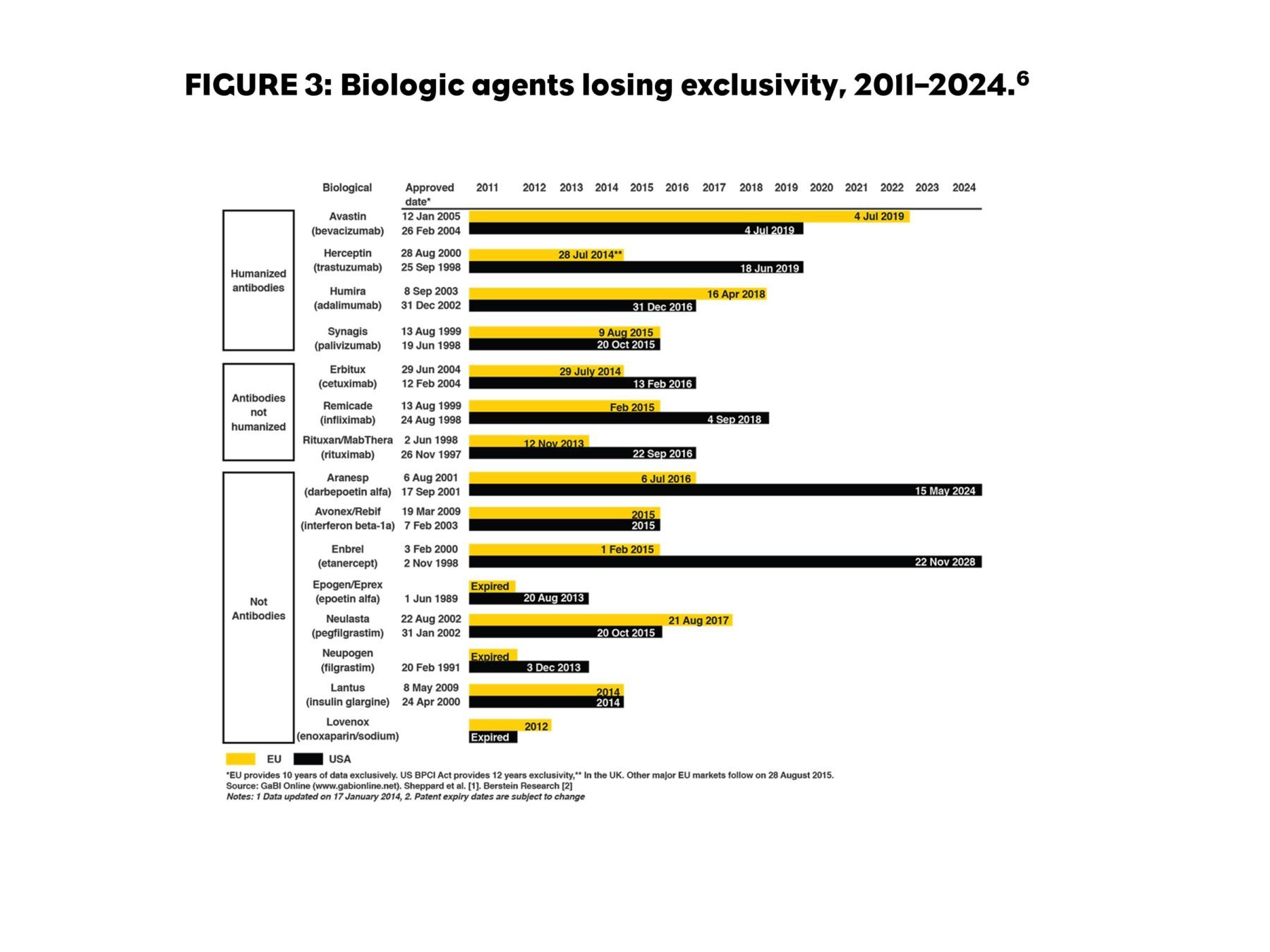

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act) was passed as part of healthcare reform that President Obama signed into law in 2010. The BPCI Act shortens the pathway to approval for biological products shown to be biosimilar or interchangeable with a product approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).4 This legislation also lengthened the patent protection for biologic products from 10 to 12 years after approval.5 Globally, biologic products representing $67 billion in sales will lose patent protection by 2020.6

Regulatory and Manufacturing Barriers May Block The Way

Regulatory Standards for Unbranded Biologics are Still in Development

The regulations for unbranded versions of biologic products (which are never referred to as generic products) have been developed and implemented rather slowly. These products have been called “follow-on biologics” or “biosimilars.”7

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and FDA regulations are written in very general terms to allow for the broad range of therapeutic categories and mechanisms of action that will need to be assessed to establish “biosimilarity.” The methodology by which they solicit and accept submissions sometimes gives the impression that they will decide what they find acceptable when they see it.

EMA Regulations

The European Union (EU) was a bit ahead of the FDA in creating pathways for biosimilar products to be introduced. As of December 2015, the EMA had approved 19 biosimilars (based on seven originator products that included epoetins alfa and zeta, filgrastim, follitropin alfa, somatropin, insulin glargine, and infliximab). According to the EMA biosimilar guidelines implemented in July 20158: “The Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: Non-clinical and clinical issues (EMEA/CHMP/BMWP/42832/05 Rev.1) lays down the non-clinical and clinical requirements for a similar biological medicinal product (‘biosimilar’)”.

The guideline provides regulatory direction on non-clinical (pharmaco-toxological assessment and study design), clinical (requirements for pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and efficacy studies, including pharmacodynamics markers, study design, patient selection, and study endpoint selection), and clinical safety and pharmacovigilance (safety, immunogenicity study design, risk management, and extrapolation of safety and efficacy). The guideline also recommends a stepwise conduct of non-clinical and clinical studies.

The EMA guidelines appear to be more comprehensive than the FDA guidelines for biosimilars, but both seem to require collaboration with regulatory authorities regarding design and execution.

FDA Regulations

The FDA regulations on biosimilars consider three key characteristics for the biosimilars approval process:

- Biosimilarity: A drug must have essentially the same function as the original product. It cannot be better or worse.

- Interchangeability: Because the products are complex molecules, even an identical protein sequence for a monoclonal antibody (mAb) could differ in receptor affinity because of differences in the folding of the protein molecule. Studies are required to indicate that product switching results in no changes in outcome.

- Extrapolation: The concept of approving a biosimilar for other indications than what were studied, assuming that the activity would be the same.

Barriers to Entry in the Biologic Market

In addition to the regulatory barriers, there is substantial cost associated with the manufacture of biologics. Just building a plant to manufacture biologics is estimated to cost up to $1 billion. This would be in addition to the other costs of clinical testing that can reach up to $200 million, compared with only $4 million for small molecule generics. Currently, only large pharmaceutical manufacturers have the internal resources to enter the biosimilar market, so several business models are evolving to expand the opportunity to other companies. Some of these models involve partnerships and licensing agreements. The resulting products will come from large companies or coalitions, potentially backed by substantial marketing resources as well.9,10

Stakeholders are not Aligned on the Role of Biosimilars

Payer Expectations of Biosimilars’ Market Effects are Complex

The customary model for loss of exclusivity on normal prescription therapies—and the price reductions that follow—may be a poor predictor of pricing for biosimilars.

When a small-molecule product loses patent protection, a single generic manufacturer who files an abbreviated new drug application is given six months of exclusivity to sell the generic. Frequently, it is sold at only a small discount (~10%) until the six months have elapsed. At that point, other generic manufacturers can enter the market. The number of generic entrants is often related to the sales volume of the originator drug and typically the price declines based upon number of generic entrants. At one year after generic introduction, originator brand market share is typically 16%.11

Because of the considerable barriers to entry for biosimilar manufacturers, there will likely be fewer biosimilars, and the first biosimilar to market will have no exclusivity period. However, the first interchangeable biosimilar will receive one-year exclusivity over subsequent biosimilars. Therefore, biosimilar pricing will be unlikely to follow generic practices.12 One response may be for pharmaceutical companies to lower prices of originators, at least somewhat, to reduce payer incentives to adopt the newer biosimilar formulations.

Lack of interchangeability may limit controls placed on brands in the category. Payers may use the threat of biosimilars to leverage pricing of originator brands. In that way, originator price reductions may change product preferences in an entire category, even if biosimilars are not made available by the plan.

Provider Expectations for Biosimilars Differ From Payer Expectations

It is unclear whether prescribers will switch patients taking originator drugs or limit use of biosimilars to new patient starts, especially if the biosimilar is not rated as interchangeable. And physicians may still be resistant to switch even when a biosimilar is labeled as interchangeable.

Further Biosimilar Ramifications Need to be Addressed

Naming Conventions

It appears likely that the international nonproprietary name (typically referred to as the “generic” name for small molecules, but avoids confusion with “generic” drugs versus biosimilars) may be required to have a suffix that identifies the manufacturer. By regulation, this suffix should contain four letters, be unique, and be devoid of meaning.

As of now, biosimilars rated as interchangeable may be permitted to have the same suffix as the originator product (two options were proposed in the FDA industry guidance published in August 2015, awaiting industry feedback). These unique names are critical for the prevention of unintended switching and for effective pharmacovigilance.13

Tracking and Continuity

Biosimilars will need to be tracked (especially in instances when they are not interchangeable). If a member receives a biosimilar product and changes plans (by changing jobs, retiring, or even changing plans at the same employer), how will the new PBM know which drug the patient has received in the past, and then ensure that the member receives the same product they were on before?

Interchangeability

The issue of biosimilar interchangeability is a complex one. Although biosimilars may be interchangeable with the originator drug, it remains to be seen if they will be interchangeable with each other. Some assume that if two agents were deemed to be interchangeable with the same originator drug, then they should also be interchangeable with each other. But what will happen when there is a mix of interchangeable and noninterchangeable biosimilars? How will plans treat them? It is likely the noninterchangeable products will be offered at a lower cost to encourage use. (Those products will have lower development costs without the interchangeability data.)

Will short-term treatments (e.g., granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for bone marrow suppression during chemotherapy) be treated differently than long-term treatments (e.g., anti–tumor necrosis factor for rheumatoid arthritis)? The emergence of biosimilars continues to complicate treatment considerations for both providers and health plans.

Provider Reimbursement for Office-Administered Products

The incentives for providers in buy-and-bill settings need to be aligned with payer intentions. A premium will be paid, in the form of a reimbursement differential, to use biosimilars—or at least to remove any disincentive created by lost profit on higher-priced branded products. Medicare plans will use a blended average sales price that combines the biosimilar and brand prices, providing a powerful incentive to use the biosimilar.14,15 Commercial plans will likely follow Medicare’s lead.

Forecasting Biosimilar Uptake in a Complex and Dynamic Environment

It seems likely that uptake for biosimilars will be slow at the start of availability because of:

- Limited discounting (the number of biosimilars and how close their launch timing is can impact the pricing structure of each individual biosimilar market).

- Originator contracting may be able to effectively maintain share by aggressive discounting, at least until multiple biosimilars are available.

- Lack of interchangeability in biosimilar labels.

- Limited indications—and where indications are extrapolated, provider reluctance to use the biosimilar.

- Lack of access uniformity; unlike the generic market, payers and PBMs may not provide access to biosimilars in a uniform fashion.

Overall, the uptake of biosimilars is seen as a positive development by payers, a negative development by originators, and an action with an uncertain outcome by providers and patients. After some initial hesitation, biosimilar uptake may be rapid for several reasons:

- Low-cost plans may require biosimilar use as a step edit. These may include the lowest cost Medicare Part D plans, Medicaid, and some exchange plans.

- Physicians may select competing products if they are sufficiently concerned with the biosimilar. Once physicians have some experience with biosimilars in these situations, they may determine that the biosimilar products are sufficiently safe and effective and allow them to be used more frequently.

- The caveat in this scenario is safety: If negative reports about the biosimilars come out—anything from product lot defects that result in recalls to investigations of side effects or mortalities—the biosimilar category will be set back substantially.

Conclusions

Specialty drug spending is the fastest growing category in healthcare, largely driven by biologics. As a result, they will be targeted for cost management. Biosimilars represent a cost-control method that, at least superficially, resembles the generic market. The enormity of the potential market is a strong incentive for all manufacturers (not just generic manufacturers) to consider this market. The complexity and evolving regulatory environment are substantial barriers to entry, and the lack of experience and clarity are potential barriers to uptake.

References:

1. Keshavan M. “Does drug pricing reflect innovation?” MedCityNews website. http://medcitynews.com/2014/12/drug-pricing-reflect-innovation-evidence-suggests. Published December 12, 2014. Accessed July 5, 2016.

2. Express Scripts. “Express Scripts 2015 drug trend report.” https://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/~/media/d82d33d9686a4c5aab31abb87ecdc73a.ashx. Published March 2016. Accessed July 8, 2016.

3. “How to manage costly specialty medications.” Optum website. http://www.optum.com.br/content/optum/en/optumrx/pharmacy-insights/costs-prices-solutions.html. Published July 24, 2014. Accessed July 5, 2016.

4. Christl L; U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “FDA’s review of the regulatory guidance for the development and approval of biosimilar products in the US.” http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/UCM428732.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2016.

5. Barry F. “U.S. FDA tweaks requirements for 12-year biologics exclusivity. BioPharma-Reporter.com website.” http://www.biopharma-reporter.com/Markets-Regulations/US-FDA-tweaks-requirements-for-12-year-biologics-exclusivity. Accessed July 5, 2016.

6. “U.S. $67 billion worth of biosimilar patents expiring before 2020.” GaBI Online Website. http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/US-67-billion-worth-of-biosimilar-patents-expiring-before-2020. Updated January 20, 2014. Accessed July 7, 2016.

7. “Information for industry (biosimilars).” U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm241720.htm. Accessed July 7, 2016.

8. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. “Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues.” http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/01/WC500180219.pdf. European Medical Association guideline EMEA/CHMP/BMWP/42832/2005 Rev 1. Published December 18, 2014. Accessed July 5, 2016.

9. Brill A; Matrix Global Advisors. “The economic viability of a U.S. biosimilars industry, February 2015.” https://www.primetherapeutics.com/content/dam/corporate/Documents/Newsroom/PrimeInsights/2015/0215-biosimilarswp.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2016.

10. Blackstone EA, Joseph PF. “The economics of biosimilars.” Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6(8):469-478.

11. Grabowski H, Long G, Mortimer R. “Recent trends in brand-name and generic drug competition.” J Med Econ. 2014;17(3):207-214.

12. Koyfman H. Biosimilarity and interchangeability in the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 and FDA’s draft guidance for industry. Biotechnol Law Rep. 2013; 32(4): 238-251.

13. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “Nonproprietary naming of biological products: guidance for industry.” http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm459987.pdf. Published August 2015. Accessed July 7, 2016.

14. “Medicare Part B drug average sales price.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Part-B-Drugs/McrPartBDrugAvgSalesPrice/Part-B-Biosimilar-Biological-Product-Payment.html. Accessed July 7, 2016.

15. Walker T. “Five reasons to be concerned over proposed Medicare rule on biosimilar coding.” Formulary Watch website. http://formularyjournal.modernmedicine.com/formulary-journal/news/5-reasons-be-concerned-over-proposed-medicare-rule-biosimilar-coding?page=0,0. Published August 10, 2015. Accessed July 7, 2016.