In our organization’s payer market research, we generally find pharmacy and medical directors respond to proposed risk- or outcomes-based contracting with muted interest. The reasons often include cost of contract management, lack of internal staff and infrastructure to extract and report the data, and inconsistent data availability across their membership. Among insurers and networks, electronic health records are often heterogeneous legacy systems from prior organizations, with limited interactivity. Typically, laboratory results might be available at the payer level, but a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) has no access to laboratory results. Making data available across these silos presents patient privacy challenges that organizations may not be willing or able to address.

The managed care marketplace has been claiming that the time had come for “value-based contracting” since 2013, but there was little actual contracting taking place until recently.1 Early movers were Merck in diabetes (Januvia/Janumet) and Sanofi in osteoporosis (Actonel), which offered value-based contracts in 2009.

Some issues with establishing relationships between product utilization and the cost of treatment involve patient selection and the advent of “big data,” which poses both benefits and challenges regarding selection. Predictive analytics provide ways to identify patient populations that could benefit most from greater support or more aggressive interventions.2 This could potentially provide more confidence that costly interventions are justifiable on a risk/benefit basis. However, the challenge here is in patient privacy, because the burden of patient privacy regulations is considerable.

Starting in 2014, we saw the use of outcomes-based contracting begin to accelerate.3 A 2015 survey by the analytics company, Avalere Health, found that interest in outcomes-based contracts was especially high in more costly areas of treatment, like hepatitis C, oncology, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.4

Current pharmaceutical product contracts are typically access based, with a tiered access system, and contracting is for 1-of-1 or 1-of-2 products in the preferred tier. In the case of highly genericized or competitive classes, the contracting extends to nonpreferred tiers. Share-based contracting is often layered on top of this, with greater discounts proportional to product market share. Performance in these scenarios is based on access and utilization rather than outcomes.

What Do New Outcomes-based Contracts Look Like?

While all drug contracting is confidential, preventing the parties from revealing the actual discounts, the performance factors are typically well characterized.

2009

- A Cigna/Merck agreement used a value-based benefit design in which patients were provided adherence incentives, and compensation to Merck was linked to blood-glucose reductions.5

- A Health Alliance Medical Plans/Procter & Gamble/Sanofi-Aventis contract allowed for limited reimbursement of fractures for patients on Actonel.5,6 The agreement performed as designed and successfully demonstrated efficacy in preventing fractures, so it never reached the agreed-upon limits for fracture reimbursement.

2015

- Harvard Pilgrim contracted with Amgen for Repatha, a cholesterol-lowering drug. If patients achieve results similar to those reported in Repatha’s clinical trials, the product is paid for at a lower level. Layered on top of this is a discount if usage surpasses a predetermined level.7

2016

- Harvard Pilgrim expanded its approach with two more deals.8

- Novartis’ Entresto for heart failure is compensated at a lower level if targeted reductions in hospitalizations are not achieved.

- Eli Lilly’s Trulicity for type 2 diabetes must outperform competing drugs to receive maximum contract revenue.

- Humana contracted with Eli Lilly for Effient, an antiplatelet drug, by linking reimbursement to potential reductions in hospitalization rates.8

- Cigna and Aetna have also contracted with Novartis for its heart failure drug, Entresto, linking increased compensation to reduced hospitalizations.

PBMs have traditionally been uninterested in this type of contracting because of the absence of medical data, thereby limiting pharmacy provider participation to specialty pharmacy providers, whose prior authorization criteria would offer at least some of the necessary data.

One novel solution has been demonstrated by the Express Scripts contract with AstraZeneca for lung cancer drug Iressa: Payment is only made for patients who receive a third prescription refill, which serves as a surrogate measure of adherence, and presumably, efficacy.9

Payer Attitude Segments

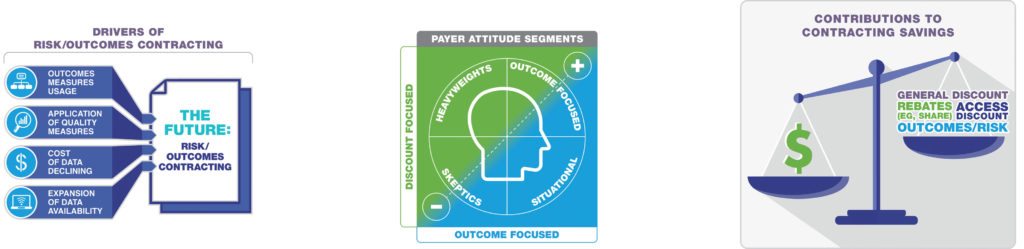

In our market research about outcomes-based contracting, we have observed four main attitudes among payers:

1. Outcome focused: These payers have a long history of outcomes-based contracting and see it as a tool to ensure that manufacturers are providing value for the price being paid. Some view these contracts as real-world evidence for the products, adding to their data on disease management and outcomes measurement. They solicit these kinds of contracts from every manufacturer and expect that such contracts will be offered with or without exclusivity.

2. Situational: These payers are mostly neutral to the offers and see each contract as a unique financial opportunity. They only consider outcomes-based contracts if the incremental financial benefit seems significant.

3. Skeptics: These payers believe that there are no situations in which a manufacturer will risk any revenue; therefore, they assume that outcomes-based contracts do not benefit payers. They often review the contracts and opt for a straight access rebate instead.

4. Heavyweights: These payers look at risk- or outcomes-based contracts to determine how much additional value is being negotiated. Then, they demand the same value without participating in the risk- or outcomes-based part of the contract. They justify such negotiations because of their organizations’ sheer size or influence, but it is unclear how often they successfully achieve what they want with these types of contracts.

What the Future Has in Store

Although the cost of managing outcomes-based contracts is currently a limiting factor, the availability of the data necessary for such contracts is expanding as quality measures and outcomes management grow. Furthermore, the cost of the data is declining as it becomes more fully integrated into our healthcare system.

The endpoints used for these contracts remain a key area for refinement. Payers want endpoints that are readily available and are not open to interpretation. Lab results are a good example: Many plans require members to use a specific lab vendor that provides member lab results under contract. This enables payers to use contract endpoints like glycosylated hemoglobin, which has been clearly linked to outcomes.

Hard data from claims represent another challenge to outcomes-based contracting because payers often lack access to members’ electronic medical records. Preventing emergency department visits and hospitalizations is highly valued, affecting both costs and quality measures, but can be difficult for payers to document.

Furthermore, many contracts only last for one to three years, but treatments for chronic illnesses may not reduce events within that limited a time frame. Softer endpoints requiring more data include chronic disease exacerbations, like those seen in multiple sclerosis. Disease exacerbations may not result in hospitalization, so surrogate endpoints (such as steroid treatment) are often used to capture events more accurately.

Navigating Outcomes-based Contracts

Other issues that will arise as outcomes-based contracts become more common is how to determine causation, and the potential for patients to receive multiple products that have outcomes tied to them. For example, can you contract for efficacy with multiple products in the same therapeutic area, such as glycosylated hemoglobin goals with both sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetes? What about outcomes that affect multiple disease states, such as reductions in emergency-department visits and/or hospitalizations with congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

Closed networks will likely be early movers in outcomes-based contracts because of integrated data systems, but insurer partnerships with data companies will enable data mining within currently siloed systems like PBMs and specialty pharmacy providers. For better or for worse, universal access to patient records is not yet on the horizon.

As outcomes-based contracts become more common, payers will start to accumulate data on their own members and develop real-world evidence to drive their outcomes-based contracting strategies. Pay-for-performance scenarios are becoming common in compensating providers, so it seems like a natural progression to expand to how pharmaceutical products will be reimbursed.

Drug manufacturers would be well advised to proactively address outcomes-based contracting with all their customers—or risk a competitor striking the deal first.

References:

1. Mehr SR. “Value-based Contracting for Pharmaceuticals: Getting Ready for Prime Time?” Am J Manage Care. 2013;19(suppl 3):SP113-SP115.

2. Lazarus D. “‘Big Data’ Could Mean Big Problems for People’s Healthcare Privacy.” Los Angeles Times. October 11, 2016. http://www.latimes.com/business/lazarus/la-fi-lazarus-big-data-healthcare-20161011-snap-story.html. Accessed November 4, 2016.

3. Loftus P, Mathews AW. “Health Insurers Push to Tie Drug Prices to Outcomes.” Wall Street Journal. May 11, 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/health-insurers-push-to-tie-drug-prices-to-outcomes-1462939262. Accessed November 4, 2016.

4. “Health Plans Are Interested in Tying Drug Payments to Patient Outcomes [news release].” Washington, DC: Avalere Health; June 16, 2016. http://avalere.com/expertise/life-sciences/insights/health-plans-are-interested-in-tying-drug-payments-to-patient-outcomes. Accessed November 4, 2016.

5. “CIGNA, Health Alliance Launch Programs with Drug Firms Based on Rx Performance.” Drug Benefit News. 2009;10(9):1, 6-8.

6. “Health Alliance Announces Promising Nine-month Results from First Ever Outcome-based Reimbursement Program for Actonel® (risedronate sodium) Tablets [news release].” Urbana, IL: Health Alliance Medical Plans; October 29, 2009. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/health-alliance-announces-promising-nine-month-results-from-first-ever-outcome-based-reimbursement-program-for-actonelr-risedronate-sodium-tablets-67198367.html. Accessed November 4, 2016.

7. Herman B. “Harvard Pilgrim Cements Risk-based Contract for Pricey Cholesterol Drug Repatha.” Modern Healthcare. November 9, 2015. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20151109/NEWS/151109899. Accessed November 4, 2016.

8. Teichert E. “Harvard Pilgrim Scores Discounts on Novartis, Lilly Drugs.” Modern Healthcare. June 28, 2016. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160628/NEWS/160629889. Accessed November 4, 2016.

9. “ASCO 2016: Keeping Cancer Therapy Within Reach.” Express Scripts website. https://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/insights/industry-updates/asco-2016-keeping-cancer-therapy-within-reach. Published May 26, 2016. Accessed November 4, 2016.