On November 3, 2021, Congress introduced a working draft of the Build Back Better (BBB) Act. This legislation includes proposals that could drive some of the most material changes in drug pricing in the history of the Medicare Parts B and D programs. The changes are sweeping, with potential for some—such as inflation rebates—to be implemented as soon as 2023.

However, the legislation is not final and currently appears unlikely to pass in its entirety. With that said, the drug pricing provisions appear to be some of the most likely provisions to be included in any related legislation, so it will be important to keep an eye on it as changes develop.

While various drafts of BBB have been circulating in both the House and the Senate, this article is consistent with the version released by the Senate Finance Committee in December 2021. Key considerations include:

- Government negotiation of Medicare drug prices

- Inflation penalties for drug pricing

- Biosimilar drug reimbursement

- Medicare Part D benefit redesign

- Reduced premiums in the exchanges

- Address Medicaid coverage gaps

We will focus on the first three considerations that are primarily targeted to reduce prescription drug prices in the U.S.

Government Negotiation of Medicare Prices

BBB grants authority for the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to select a subset of Medicare Part B and D drugs and establishes a maximum fair price (MFP) based on time in the market and competition.

If the act is passed, the basket of products to be included in negotiations is expected to be announced in early 2023, with negotiations kicking off soon after. Medicare plan sponsors would need to use this information to meet a June 2024 deadline for bid submission, with formularies reflecting MFP dynamics going into effect January 1, 2025.

The scope of these proposed rules would have different impact given a manufacturer’s portfolio, but companies can evaluate any potential impact by focusing on three areas:

1. Eligibility

The MFP negotiation is targeted at the 50 highest-spend drugs for the Medicare Part D and the 50 highest-spend drugs for the Medicare Part B program. These products are identifiable using data and dashboards furnished by CMS. Rollout of negotiations is staged over four years and intended to be incremental, with up to 10 drugs included in 2025. As part of reviewing eligibility, it should be noted that some drugs will not be considered or will have different rules:

- Orphan drugs, as defined as a drug intended to treat a condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people.

- Low-spend Medicare drugs, defined as drugs with less than $200 million in expenditures.

- Drugs manufactured by “small biotech” companies would be exempt from negotiation through 2027.

A limited set of manufacturers is likely to be impacted by these negotiations, but the impact for those manufacturers may be material.

2. Versus Status Quo

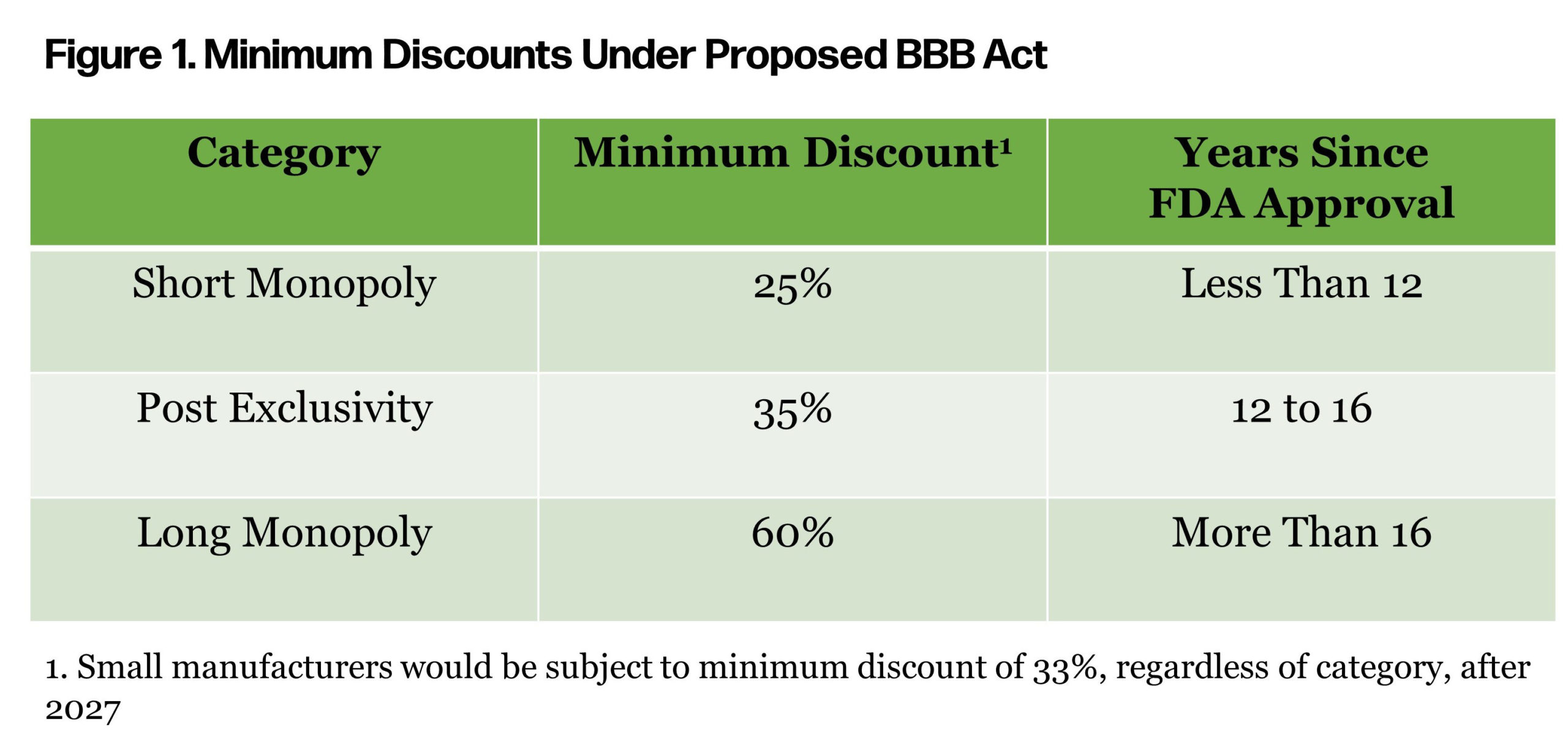

The minimum discounts mentioned in the proposed act vary by years since approval by the FDA (Figure 1). Some of the drugs that top the Medicare spend report have been in the market since the early 2000s.

As manufacturers evaluate potential risk, an understanding of the status quo is important. Medicare market access strategy can vary significantly depending on factors such as competition, protected class status, and biosimilar or generic availability. A strategic assessment should focus on the net effective rebate provided across Medicare, but also consider nuance for rebate variation by Medicare carrier. Other important nuances to capture include:

As manufacturers evaluate potential risk, an understanding of the status quo is important. Medicare market access strategy can vary significantly depending on factors such as competition, protected class status, and biosimilar or generic availability. A strategic assessment should focus on the net effective rebate provided across Medicare, but also consider nuance for rebate variation by Medicare carrier. Other important nuances to capture include:

- Coverage Gap Discount Program (CGDP) Trade-off: Products that are selected for government price negotiations would be exempt from the expanded manufacturer discount program payments.

- Best Price Implications: Today, Medicare Part D rebates and discounts are not considered as part of “best price” considerations. If implemented, BBB would carve-in any government negotiated discounts into the best price.

Beyond the direct financial considerations, it is unclear how minimum discounts and government price negotiations may disrupt existing coverage paradigms. Top-spend Medicare Part D products with overlapping indications include, but are not limited to: 1) Eliquis and Xarelto; 2) Humira, Enbrel, and Stelara; and 3) Trulicity and Victoza. With a limited number of products expected to be selected for negotiation, the process has the potential to apply significant gross-to-net pressure in a class or to create “winners” and “losers.”

Winners may continue to have access but at a lower gross-to-net and losers may not be covered, may be managed, or may be stepped through preferred products. If the act is approved, it will be important to understand how information will be shared between HHS, CMS, Medicare carriers, and manufacturers.

3. Planning

If BBB is enacted and a manufacturer expects a product may be included in the scope of government negotiations, they should:

- Identify strategic options, both proactive and responsive to government negotiation or increased gross-to-net or competitive pressure.

- Assess the short-term and long-term impact of potential changes to access and new utilization management.

- Consider financial reserving needs and communications to the street with regard to forecasts and expectations.

Government negotiation of Medicare Part B and Part D pricing may result in reduced Medicare program cost. The scope of the impact is narrow across products, but has the potential to significantly impact the financials of the manufacturers that market those products.

Inflation Penalties

Another component of the proposed BBB Act borrows a convention from the Medicaid program to create an inflation rebate. This would be triggered when a product’s price increases exceed the consumer price index (CPI-U). Year-to-year drug price increases exceeding inflation are not uncommon. The BBB Act would require drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to the federal government if their prices for medicines covered under Medicare Part B and Part D increase faster than CPI-U. For price increases higher than inflation, manufacturers would be required to pay the difference in the form of a rebate to Medicare.

With regard to program contours, a few key things to note are:

- The inflation rebate would take effect in 2023.

- Average manufacturer price (AMP) would be the basis for Part D drugs, and average selling price (ASP) would be the basis for Medicare Part B drugs.

With these proposed changes, manufacturers would need to be mindful of their pricing strategies over the lifetime of an asset. For products in launch planning, a thoughtful pricing strategy becomes even more important as price increases in excess of CPI-U will have the potential to rapidly erode gross-to-net margin and in some cases, as seen in the Medicaid program, result in “penny price” drugs.

The financial and forecasting exercise around pricing will become a more complicated discussion, but effected manufacturers should:

- Learn from Medicaid pricing experts, as many of the considerations will port from Medicaid to Medicare.

- Educate leadership, brand, and asset teams on the dynamics of inflation rebate penalties. Price increases may not be a lever for closing forecast shortfalls in a way they once were.

- Evaluate historical AMP and ASP trends as pricing actions as far back as 2021 could influence inflation rebate penalties.

- Establish a new standard operating procedure for reviewing the impact and approving any future price increases.

Though these inflation rebate penalties already exist in the Medicaid market, introducing them to Medicare may change the calculus as manufacturers consider price increases. This dynamic could be compounded if these rebates are extended to the broader private health coverage market.

Biosimilar Reimbursement Changes

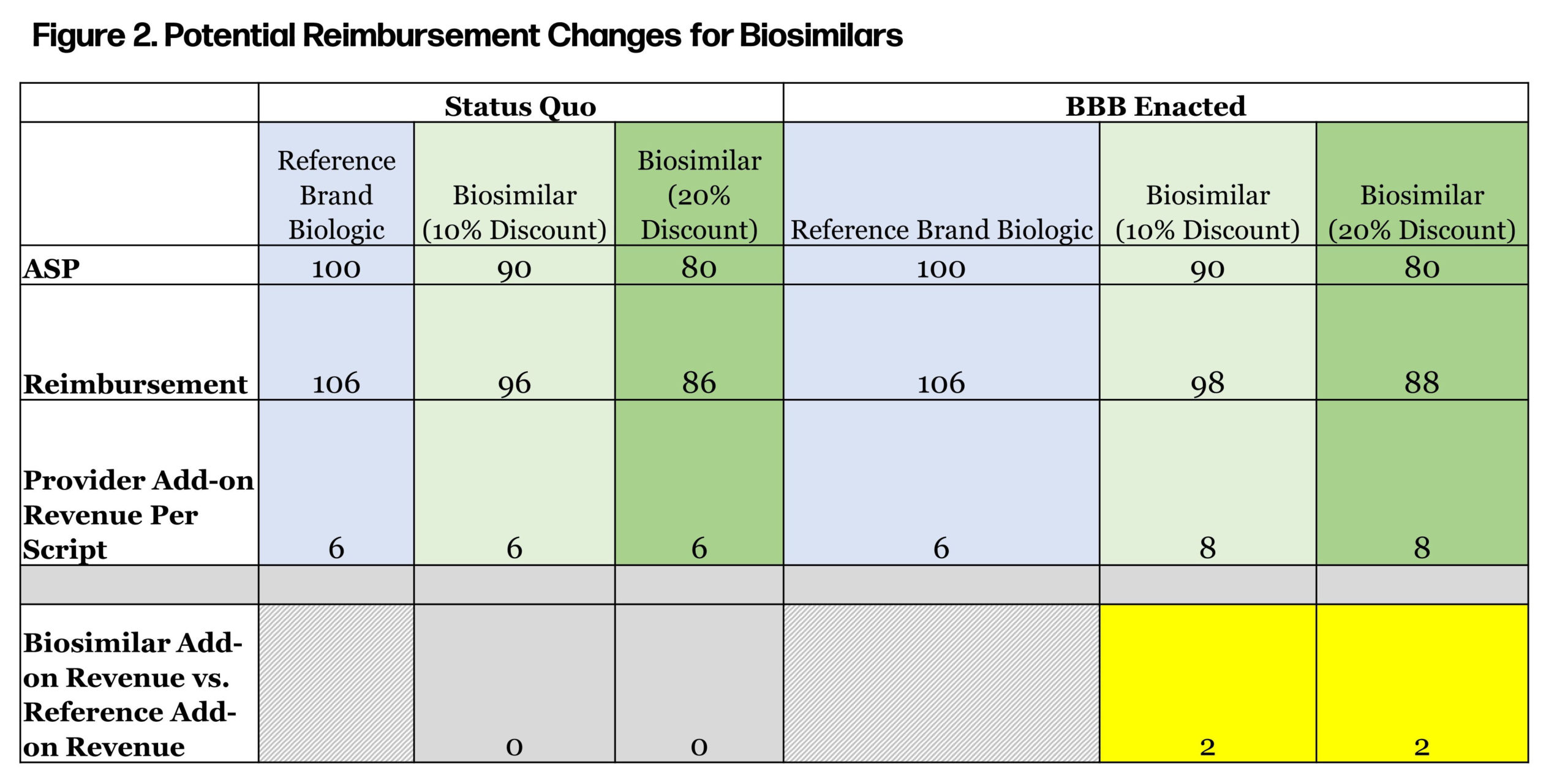

For a temporary five-year period (April 1, 2022, to March 31, 2027), Medicare Part B reimbursement for biosimilars would increase from 106% of ASP to 108% of ASP. Today, biosimilars under Part B are reimbursed as (ASP of biosimilar) + (6% of ASP of reference product). This reimbursement approach provides parity reimbursement, regardless of whether the provider administers a brand biologic or biosimilar. Under BBB, reimbursement for biosimilars would include an incremental 2% indexed to the innovator, regardless of how the biosimilar is priced. This provides an additional incentive for providers to use biosimilars (see Figure 2).

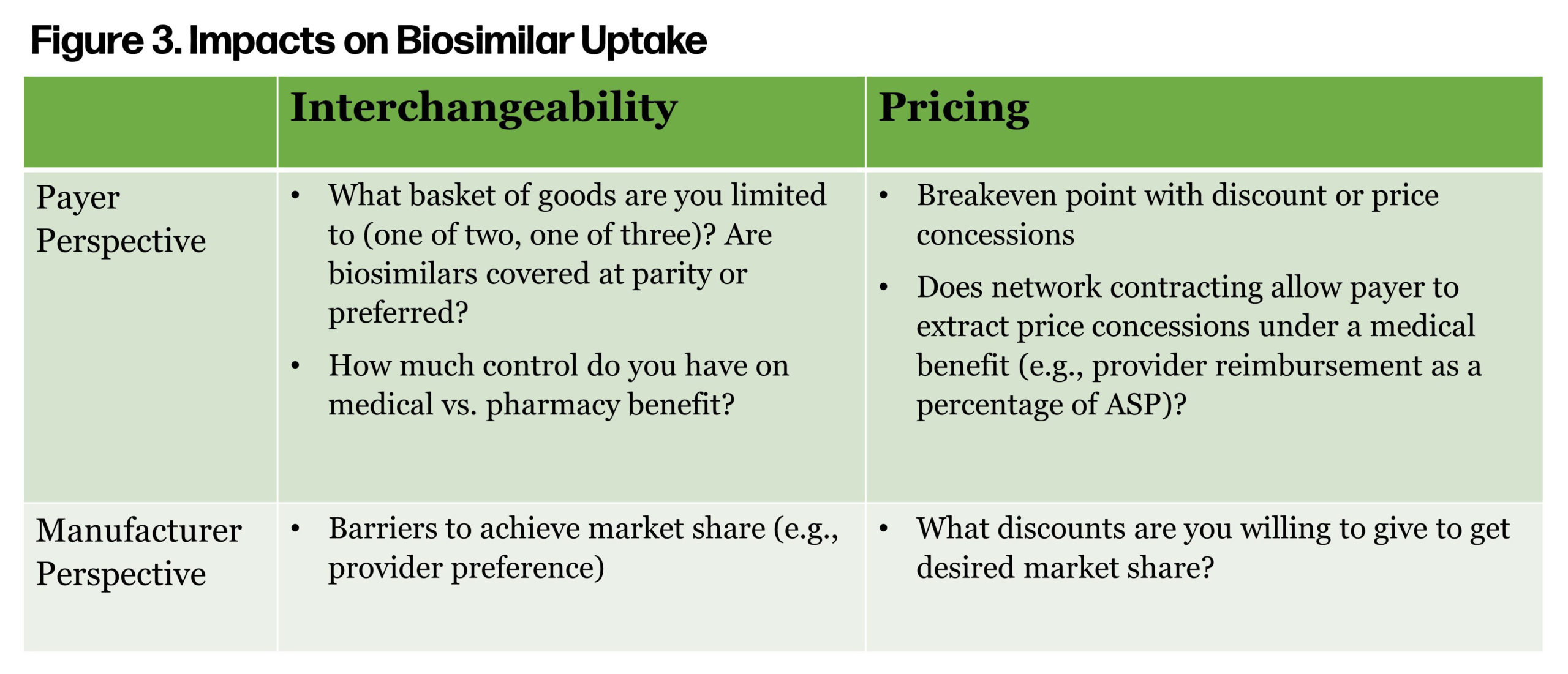

Historically, follow-on products have led to significant cost savings for Americans and have been a primary driver of prescription trend controls. However, if the price difference between the brand drug, subject to the HHS secretary’s price controls, is marginal, then the ability of a biosimilar to gain market share will be reduced. Avalere estimated CMS direct negotiations and price controls will result in a reduction in provider reimbursement for biologics, medicines, and services. Will this have an adverse impact on biosimilar uptake? Figure 3 considers some of the key drivers of biosimilar uptake from a payer and provider perspective.

Historically, follow-on products have led to significant cost savings for Americans and have been a primary driver of prescription trend controls. However, if the price difference between the brand drug, subject to the HHS secretary’s price controls, is marginal, then the ability of a biosimilar to gain market share will be reduced. Avalere estimated CMS direct negotiations and price controls will result in a reduction in provider reimbursement for biologics, medicines, and services. Will this have an adverse impact on biosimilar uptake? Figure 3 considers some of the key drivers of biosimilar uptake from a payer and provider perspective.

The highest revenue biologic, Humira (adalimumab), is expected to be available as a biosimilar in early 2023, with multiple competitors by late 2023. More payers are covering biosimilars at parity or preferred over reference products, resulting in increased uptake. However, biosimilar drug approvals are based on indication, which provides a challenge when the reference drug, such as Humira, has a lot of indications.

The highest revenue biologic, Humira (adalimumab), is expected to be available as a biosimilar in early 2023, with multiple competitors by late 2023. More payers are covering biosimilars at parity or preferred over reference products, resulting in increased uptake. However, biosimilar drug approvals are based on indication, which provides a challenge when the reference drug, such as Humira, has a lot of indications.

One approach the FDA could take is “indication extrapolation”—where the FDA reviews biosimilars on a case to approve the drug for one or all indications of the reference product. This strategy would likely result in increased patient and provider preference of the biosimilar. The other unknown is the loss of rebates for the reference product. Biosimilars are unable to match the rebates for the reference product without dominant market share. However, biosimilar manufacturers may offer some rebates to help offset a portion of the loss in rebate dollars for the reference product.

Another issue to consider is the impact of “white bagging,” a common payer strategy for buy and bill drugs where providers are only reimbursed for administration and professional services, while the drug acquisition processes are owned by the network pharmacies. If a payer applies the “white bagging” strategy to both reference brand and biosimilar, and do not differentiate reimbursement, we should expect no adverse impact. However, a payer may want to incentivize prescribing by increasing the professional service fee, perhaps through a “biosimilar bonus,” similar to the Oncology Care Model, where CMS incentivizes prescribers to use biosimilar medications.

The open question is, who will make the first move? Will payers and manufacturers wait for regulations to drive changes? Or are there enough pain points and momentum in the current environment to incentivize a fundamental shift in drug pricing and reimbursement?