The old adage “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink,” rings true when it comes to adherence to medication and other treatment recommendations. Modern medicine can offer a diagnosis, a treatment and knowledge about the condition, but unless an individual is motivated to adhere, efforts to promote adherence can be futile.

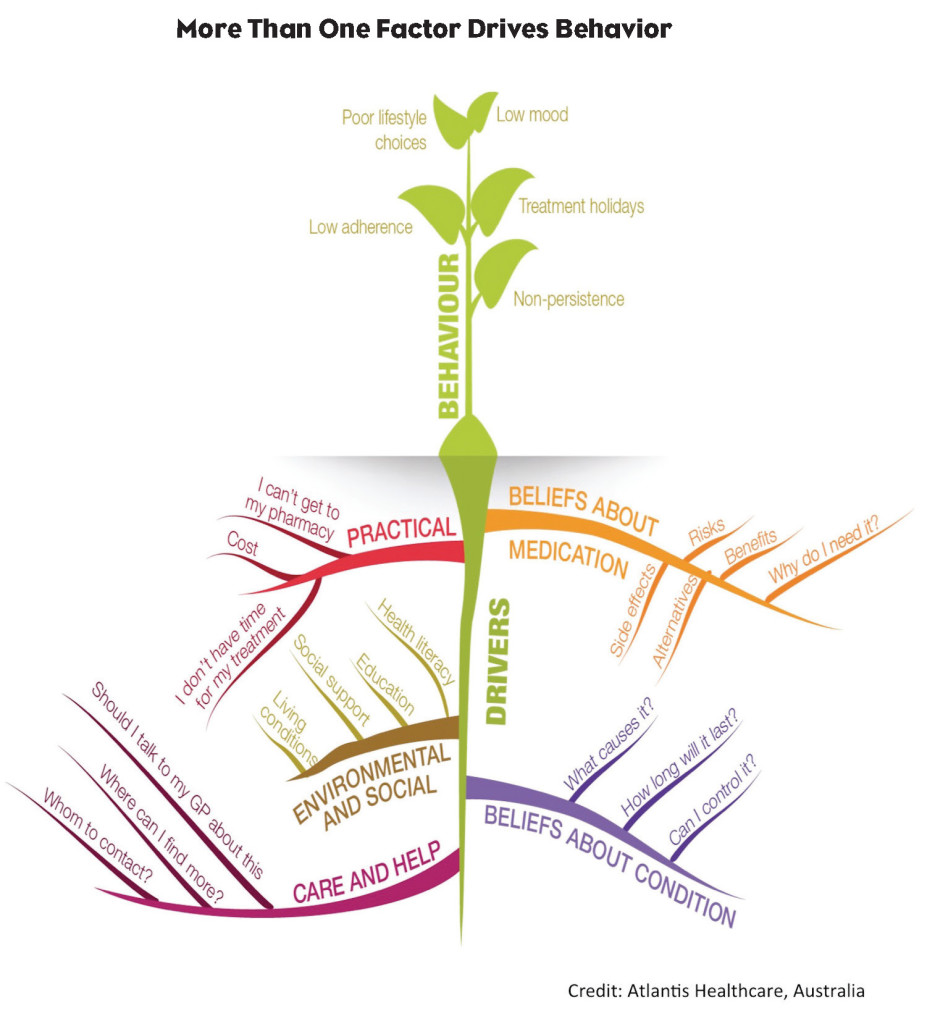

Each person brings his/her own perception of his/her situation to the adherence challenge, which is not based solely on information but also includes the individual’s personal experiences (both conscious and unconscious). This impacts motivation and behavior. Therefore, recognizing that each individual is different is key to understanding that motivators and barriers to adherence are personal. It also means the approach to addressing belief motivators and barriers must be individual.

Some pharma clients argue that there must be a way to simplify support programs using standard motivators and barriers. Objectively, it appears we should be able to come up with a fairly comprehensive list of barriers (side effects, burden, etc.) and motivators (feeling better, reducing disease burden, extending life, etc.). But this is just a reflection of our own perceptions from the outside looking in. In reality, motivators and barriers are very subjective.

Motivators Are Personal

For example, for some individuals, a potential decrease in disease burden may not be worth treatment side effects. Or, a treatment that extends life but does not improve its quality may not generate enough motivation to be adherent to treatment. It is important to recognize that despite sharing a diagnosis or treatment with other people, treatment adherence (and its motivators and barriers) are very much personal.

So how can we support an individual during their diagnostic or clinical journey when an infinite number of barriers and motivators are possible? Health psychology would have us look to the scientific process for an answer. By using the health psychology process and frameworks, we can understand and evaluate the relevant factors in a pragmatic fashion to predict behaviors and change outcomes. This becomes a two-step process—conducting research to understand the patient group, the disease state and the treatment, and then using the findings to create a screener to assess people at an individual level. It is this second phase that is the critical juncture.

Know Why Patients Don’t Adhere

Pharma clients often say they have already done all the research—they know exactly what and who needs to be targeted to improve adherence. They may have already divided the population into segments. Sometimes these are grouped by demographic (age, gender, socioeconomics, etc.), and sometimes they are grouped based on other factors such as willingness or readiness to change (hesitant, cautiously optimistic, doctor defying). Occasionally it is even a combination of several components. While this is certainly one method of targeting people for adherence, it usually isn’t the right one because knowing the what and the who isn’t enough. Without understanding why people are nonadherent, segmenting them by other characteristics is unlikely to be helpful. Consider this example:

Three women have all been segmented in one group. They are all aged 50-60, diagnosed two to five years ago with diabetes, have adequate insurance coverage, have good relationships with their HCP team and are ready to begin a new treatment. Based on these methods of segmentation, they would all benefit from the same messages on the same topics, right? Wrong. Here is why:

- Sally is really unsure that she has diabetes. From everything she has read, she thinks she is borderline at best.

- Karen believes she has diabetes but isn’t so sure about adding another treatment onto what she is already doing. She is really busy with work and at home, and doesn’t want to deal with adding another time-consuming treatment.

- Ruth understands and agrees with the diagnosis, is retired, is taking only one other medication, but is very worried about taking a medication that has just completed clinical trials. Her HCP has not explained the drug’s efficacy and she doesn’t want to be seen as “difficult” by asking more questions.

If these individuals were treated as one segment, they may receive messages on lifestyle, diabetes control or medication benefits—or even all three, depending on what research indicates as common barriers or motivators for the population. If Ruth received these messages in the order listed above she may never read beyond the first or second message because she does not perceive them as relevant. By the time she receives information on treatment efficacy, she may have already disengaged from the program tactics. Similarly, if the messages she receives don’t mesh with her engagement style (whether that be channel preference, learning style or type of behavior change technique) she will disengage. It is critical to have the right message (topic and style) delivered to the right person at the right point in time. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, you can’t successfully address a secondary (or lesser) need until the base needs have adequately been addressed.

We also know that providing information alone isn’t enough. If it was, we would each be the ideal weight, drink the perfect amount of water and exercise moderately several times a week (and if you do—bravo!). While we know these things are good for us, for many that knowledge alone isn’t enough to change our behavior. Knowledge has to be understood and applied. This takes effort.

So, back to leading the horse to water. The only way to move the adherence needle is to motivate people to be engaged in long-term adherence. Not by using information, not through demanding compliance, but by understanding and recognizing someone’s specific beliefs and engaging them through behavioral change techniques to think and act differently. This engagement means you must recognize that it is an individual’s journey and that you are merely a guide. It also means that, through engagement, once someone recognizes the beliefs and other factors that are driving their behavior, they are more likely to be adherent long term—without information, reminders, or even a guide. That is true adherence.

Resources:

Maslow AH. (1943) “A theory of human motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

McHorney CA & Spain, CV (2010) “Frequency of and reasons for medication on-fulfillment and non-persistence among American adults with chronic disease in 2008.” Health Expectations, 14, pp. 307–320.