The treatment options for the deadliest form of skin cancer had remained stagnant for the past 20 years, but the recent addition of two new therapies has significantly changed the market dynamics of this therapeutic class.

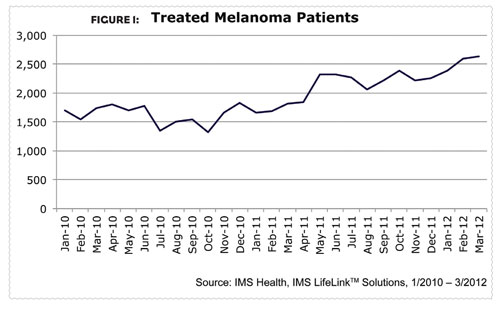

According to the National Cancer Institute, each year over two million patients are diagnosed with skin cancer, which is the most common type of cancer. Of the three types of skin cancer (basel cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma), malignant melanoma is the least common but also the most deadly. About two-thirds of skin cancer deaths are among patients with malignant melanoma, and that number may only get higher as melanoma incidence rates have been increasing for at least 30 years. Since 2004, incidence rates among Caucasian patients have increased by almost three percent each year. From March 2010 to March 2012, the number of patients being treated for melanoma increased almost 52 percent (Figure 1).

Melanoma is cancer of the melanocyte cells, i.e., those that produce pigment. For early-stage melanoma, initial treatment—and sometimes the only treatment necessary—is surgery to remove the tumor. If the tumor is thick or the melanoma has metastasized, the disease is more severe and requires further treatment. Like most malignancies, the outcome of melanoma depends largely on the stage of diagnosis.

Treatment Options

Until recently, oncologists had limited treatment options for advanced melanoma. In fact, the most commonly used therapies were over 20 years old. But in 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two new therapies for metastasized melanoma. The introduction of these therapies represents more launches in this therapeutic class than have happened in the last two decades.

In March 2011, Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Yervoy (ipilimumab) was approved for the treatment of melanoma that cannot be surgically removed or has metastasized. The drug stimulates the immune system to attack melanoma cells. In August 2011, Zelboraf (vermurafenib) from Genentech/Daiichi-Sankyo was approved for treatment of metastatic melanoma with the BRAFv600E mutation.

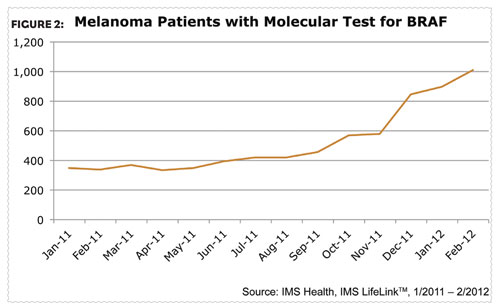

With the addition of these new options, the selection of initial therapy in patients with advanced melanoma now requires a greater understanding of the mechanisms of their disease. As researchers gained a better understanding of the underlying biology of malignancies, it was found that BRAF (v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1) was associated with various cancers, including non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma, colorectal cancer, malignant melanoma, thyroid carcinoma, non-small cCell lung carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma of the lung. In order for patients to receive Zelboraf they need a diagnostic test confirming their BRAF mutation and the use of this diagnostic test has continued to steadily increase over the past year (Figure 2). Yervoy, an immunotherapy, can be given to patients with or without the BRAF mutation.

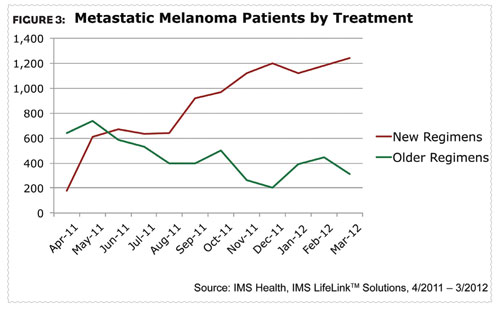

With the recent launches of these two products, the melanoma landscape is beginning to look very different. New treatment usage is increasing as older regimen use is declining (Figure 3). Physicians have embraced the newer treatment options since their introduction. In March 2012, one year after the launch of Yervoy, metastatic melanoma patients on newer regimens outpaced those on older regimens by a ratio of four-to-one.

Addressing which therapy should be first administered is a conundrum for oncologists given each therapy’s distinct and different mechanisms of action. The speed of response needs to be considered when selecting initial therapy. The immunotherapy ipilimumab can take many weeks or months before a patient has a notable response, whereas the BRAF inhibitor Zelboraf begins working almost instantaneously. The majority of patients who receive Zelboraf, however, will require a second therapy for their metastatic melanoma.

Sequencing the newer treatments appears to be the logical approach, but not all patients are candidates for Zelboraf. Oncologists are also unsure of what treatment to give patients who lack a BRAF mutation after they have progressed on ipilimumab. To date, there are no head-to-head trials evaluating vemurafenib and ipilimumab.

Knowing who the right patient subtypes are within this segment is critical in understanding market dynamics for this therapeutic class, while how patients are selected for initial therapy has become more dependent on the patients’ underlying disease characteristics than ever before.

TARGETING SPECIALISTS

Since melanoma is often initially treated surgically by dermatologists and surgeons, understanding the tumor biology and the associated genetics of melanoma has become more important than ever. The basics of tumor pathology need to be addressed, including the type of melanoma, the mitotic rate (i.e., how fast tumor cells are dividing), growth phase, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, as well as incorporating the assessment for a BRAF mutation.

Understanding the interplay between the dermatologists who diagnose and the oncologists who treat patients with melanoma is critical. Brand teams need to be aware of which specialties are managing these patients and at what point specific local and targeted therapies are clinically appropriate for use.

These new melanoma treatments have significantly changed the market dynamics, including increased therapy options, the need for specialized testing, and more positive patient outcomes. The pipeline for melanoma therapies is robust and includes melanoma vaccines, next-generation BRAF inhibitors, MEK inhibitors and future immunotherapies. With these new developments being evaluated in in the near future.