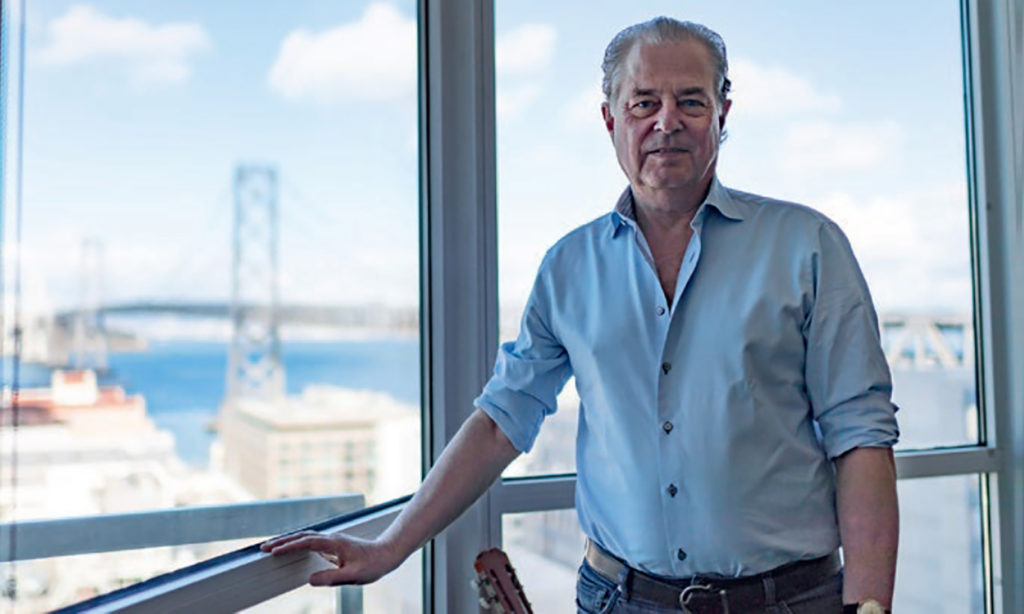

Doctors and scientists have long struggled to detect and monitor neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, but NeuraMetrix has made a breakthrough with its ability to measure brain health using a digital bio-marker based on inconsistency of typing cadence. PM360 spoke with Jan Samzelius, Founder, CEO, and CTO, about how he discovered the promise of using typing cadence to measure brain disease, its effectiveness, and the ability to use it to detect any brain disease in the future.

PM360: How did you get the idea for this company?

Jan Samzelius: I’ve been involved in many startups. In this case, it was sort of a coincidence and an accident. Most of us come from data security, and around 2012 we decided to try to rid the world of passwords.

We reached the main hypothesis that typing cadence should be ideal for authentication. It’s long been proven that it’s individual and it delivers a lot of data that has very low invariability because it’s all binary—a key is either up or down. We found data a university collected on 55 students, and as I was going through that I saw dozens of data points—all within 1/100th of a second—for one particular user for one particular key for how long he was holding it down every time he hit it.

The human body does not do anything else so consistently, which made typing absolutely ideal for authentication. So, we started to build an enterprise system for continuous authentication of employees. And one day, during a presentation, somebody said, “I bet that can also be used to detect Alzheimer’s.”

Someone just presented that idea to you?

Someone just presented that idea to you?

Yeah, and we just said, “Say what?” None of us had any medical background or any personal experience of Alzheimer’s. But it sounded intriguing.

I got a meeting with Bob Mahley, MD, PhD, Founder of Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco who had spent his last 25 years working on Alzheimer’s. After 15 minutes of explaining what we were working on, he held up his hand and said, “Stop…you realize we’ve been looking for this for 30 years.”

I just about fell off the chair. That afternoon, we put the authentication solution on the shelf and decided to go whole hog with the medical application.

How accurately can you determine if a person has a disease?

We performed a study using the Michael J. Fox Foundation’s Fox Trial Finder, which is basically a marketplace where volunteers can sign up for clinical trials. We ended up with 87 patients and 67 controls, and we collected 65 million data points over three months. I learned that 85% accuracy in determining a patient versus a control was considered pretty good in neurology. Well, ours was 99% followed by 33 more nines.

What are you monitoring in order to make your determinations?

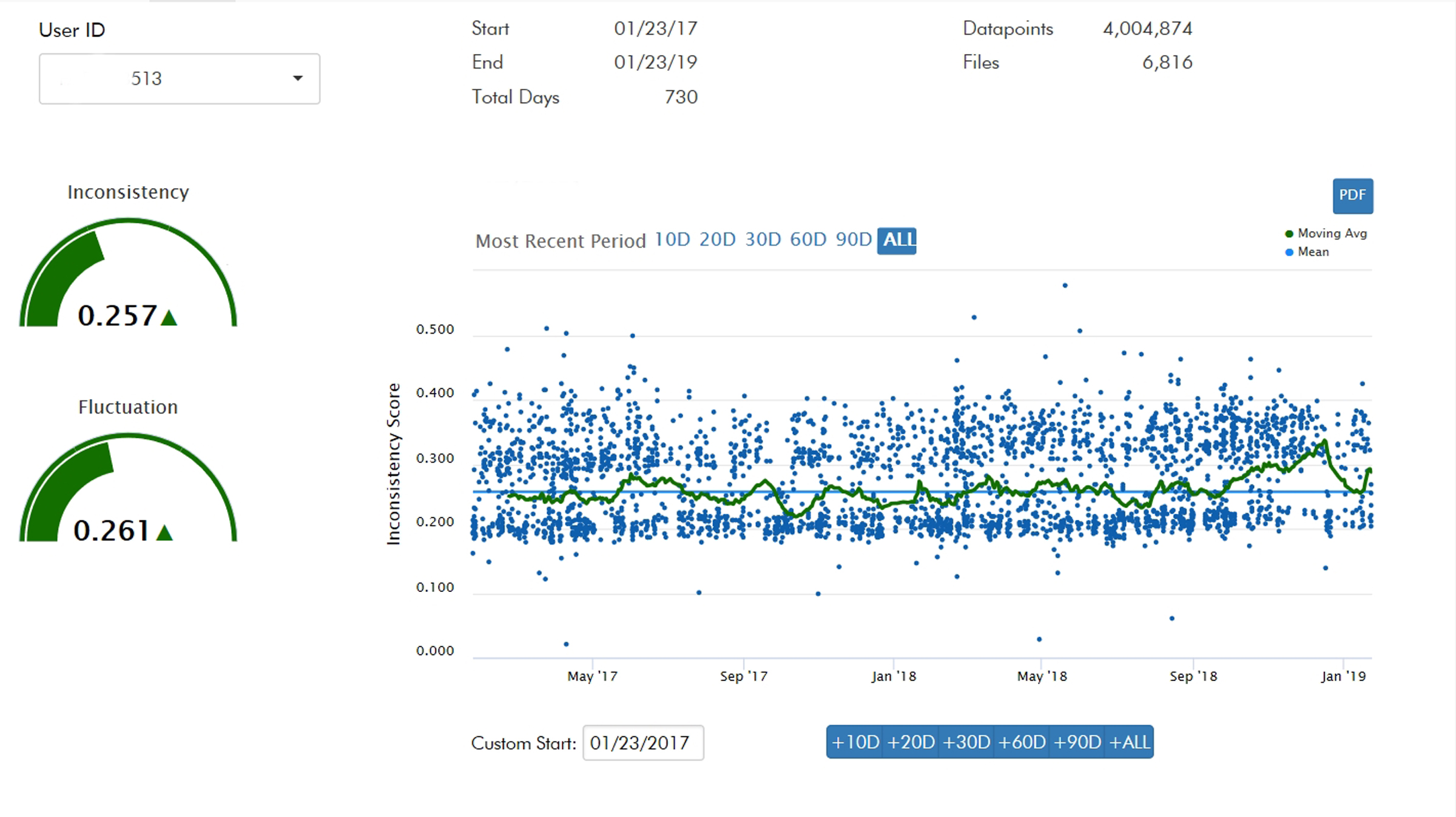

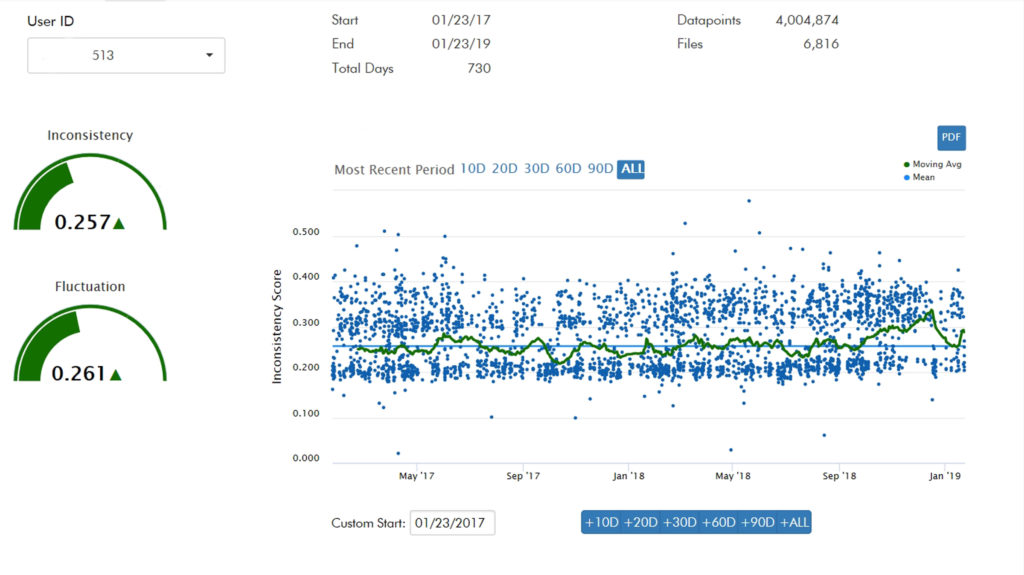

We measure inconsistency. Typing is extensively hardwired in our brains. But when the brain gets attacked by disease the wiring will begin to break, but it will break very slowly and in very small increments. It doesn’t matter how fast you type or if you are a touch-typist or a hunt-and-pecker. What makes a difference is the habit. Since we measure in milliseconds, we have been able to show that we can statistically see changes in that habit to the tune of 1/100th of a second. So, our tools should be able to see these diseases long before clinicians see them or patients feel them.

In January, the FDA granted you Breakthrough Device designation for Parkinson’s monitoring. So, how can your application be used to help patients?

One way is with monitoring diagnosed patients, because today there is no feedback loop. In many ways, doctors are flying blind because if they change the medication or anything else, then they have no real way of knowing if it worked. With our tool, the doctor and his patient will be able to go into our portal three to four weeks later and see if the changes worked. Another area is clinical trials, especially with Alzheimer’s drug trials, which are known to fail a lot due to inherent high variability of the measurements being used. But the Holy Grail is early detection, which is something we are working towards.

Will you be able to specify whether a patient has a specific neurological disease or just determine if they are at risk for one?

I’m working on that right now. We get a reliable sample on 400 variables by measuring typing cadence. Presuming that every disease and every version of a disease will manifest itself differently in those 400 variables, then we should be able to create fingerprints for the various diseases. Currently, we have good data on Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and on REM behavior disorder, and we’ll soon have some on Alzheimer’s, so the hope is we can compare those to each other and the controls in order to find distinctions.

What are your long-term goals for the company?

We have a very long list of diseases to deal with. Just starting with traditional CNS diseases, there are over 400. We also have the entire field of psychiatry and brain injuries, and four scientists also swear we can predict strokes. So, we have plenty to do. The grand vision is just about everybody would be monitored all the time to the point that people will forget that it’s actually there, and will never hear from it unless there is a reason to go to the doctor.