Physician “burnout” is not a new concern, but it is a growing one. And if the pharmaceutical industry wants to live up to its claim of being “customer centric,” we need to start to consider what we can do to help to reverse this trend.

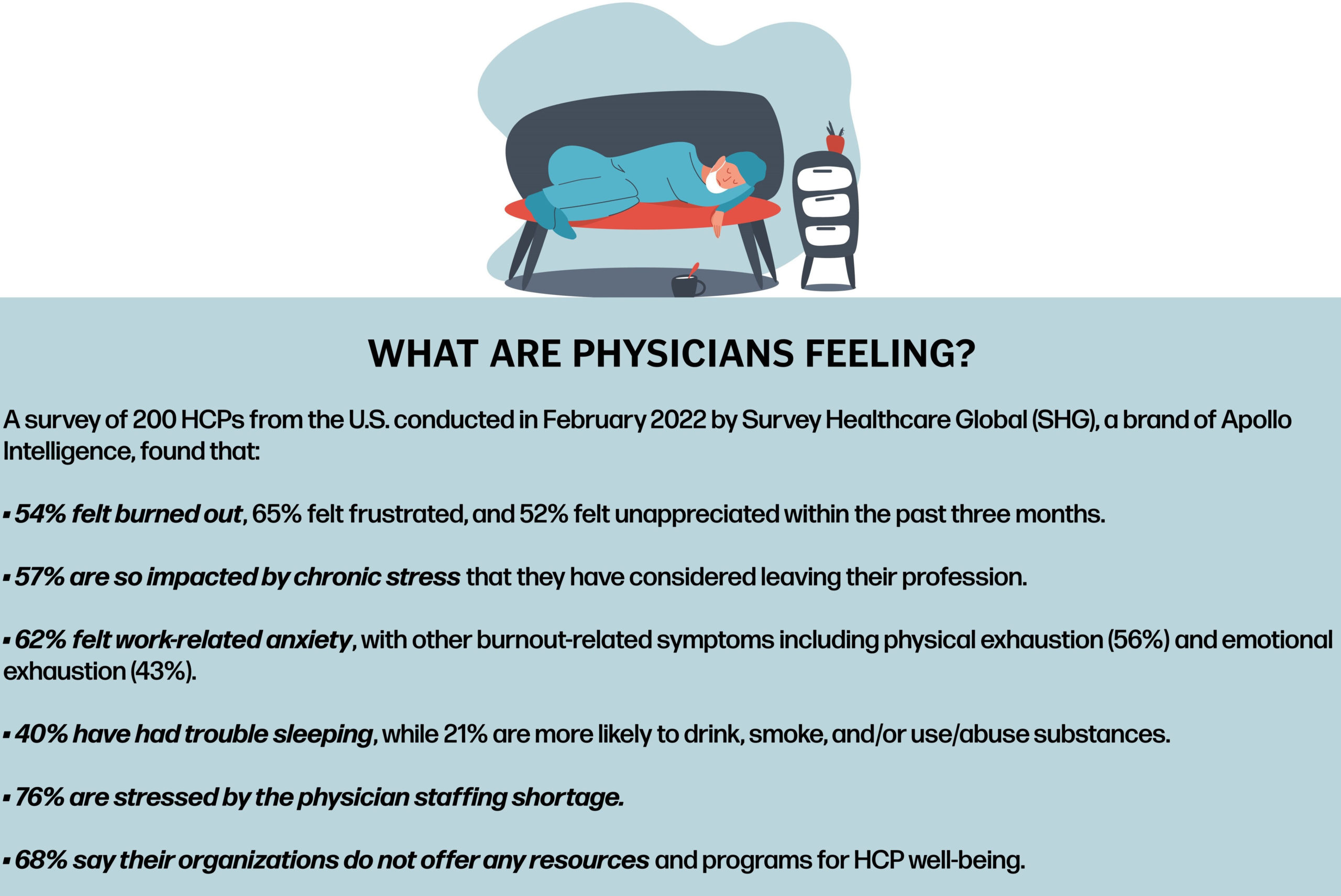

In terms of prevalence, numerous surveys have found that 40% to 50% of U.S. physicians report feeling burned out, with those numbers varying with physician age and specialty. Numerous studies have also found that the leading cause of burnout is not in treating patients, but rather the “administrative hassle” that comes with the practice of medicine. The amount of time physicians spend dealing with “paperwork” and electronic patient records is a substantial causative factor here. It takes time away from treating patients, which is what they originally went in to medicine to do.

More recently, COVID-19 has added significantly to the panoply of physician stresses and resulting mental health problems. Patients disappearing for months at a time, wreaking havoc with practice flow and finances, safety precautions aimed at infection control, a forced transition to telehealth, and numerous other results of the pandemic have been piled on top of the traditional causes of burnout.

The manifestations of burnout are far from benign. Physician anxiety and depression, an increase in the number and severity of medical errors, doctors prematurely retiring from the practice of medicine, and even suicide are all of great concern.

The solution? Sadly, “dealing” with physician burnout is most often seen in the form of “support programs” offered by medical societies and institutions that typically attempt to deal with the results of physician burnout, rather than working on eliminating its causes.

The Pharma Industry’s Response

The Pharma Industry’s Response

So, what should the pharmaceutical industry do by way of response to physician burnout? First and foremost, we need to recognize the problems that physician burnout causes us. The most carefully tailored promotional message for an important new product will be for naught if we try to deliver it to a physician whose attention is short circuited by anxiety and depression.

To get more specific insights as to what pharmaceutical companies should be doing about physician burnout, I put my training as a psychologist to work every month by holding one hour Zoom “conversations” with individual physicians. These aren’t “interviews.” There is no questionnaire or topical guide. Rather, I simply tell my respondent quite honestly that I am looking to understand what is “on her mind” at the moment, get out of the way, and let her talk.

Having personally conducted these conversations for the last 18 months, I learned the following five “tricks” for serving burned out physicians.

1. We Need to Reconsider Our Terminology

As usual, words matter here, and a lot of them are in play, both appropriate and inappropriate, for use in pharmaceutical marketing in 2022. A word falling into disfavor in pharmaceutical marketing, for example, is “sales.” The physicians we speak to are quite clear when they say they do not want to be “sold.” “Drug reps” who employ “used car salesman tactics” are frequently screened out of the office by physicians.

Conversely, words that are on the upswing of appropriateness in 2022 include engagement. In an omnichannel environment, approaches that “add value to customer experiences” and “build relationships” are increasingly important, especially with burned out physicians.

On a related note, we are seeing terminology like “Customer Experience” and its shorthand form, “CX,” increasingly moving into pharma marketing from virtually every other industry. Working to ensure positive CX for physicians is much more valuable than simply laying claim to being “customer centric.”

2. We Need to Be “Respectful of Physicians’ Time”

Through our conversations with physicians, we have learned that this expression, which is one that they themselves often use, is of utmost importance. A prime example is doctors’ disdain for “reminder details.” Telling doctors “things they already know” is seen as both wasteful of their time and insulting.

Burned out physicians—in fact all physicians—want to be in the “driver’s seat” regarding how their time is used. One of the advantages of dealing with representatives who rely on “drop by” visits is that the doctor gets to decide whether she will speak to the rep at all, and if so, for how long. “A few minutes,” “about five minutes,” and similar phrases are used to describe the length of the average “drop by” visit.

3. We Need to Recognize That Most Doctors Prefer “Live” Rather Than “Virtual” Engagements

Although many pundits have predicted that all engagements will soon be virtual, the majority of doctors offer several good reasons for preferring in-person visits by representatives. The first is that virtual engagements need to be scheduled in advance, with most doctors claiming that they are unable, or at least unwilling, to make this commitment. Typically, virtual presentations last at least 15 minutes, which most doctors see as being far too long. And, once a virtual presentation has started, doctors feel “trapped,” i.e., duty bound to listen to the end, even if no new information is being provided.

But some doctors learned to prefer virtual presentations when they became exposed to them during the pandemic. For these doctors, the ability to set aside the specific time for a virtual engagement, and thus avoid the interruption inherent in “drop by” visits, is seen as a plus.

The bottom line is that doctors vary in their preferences for live versus virtual engagements, and that these preferences are rather strongly held. The industry can better deal with burned out physicians, and with those likely to become burned out, by engaging with individual doctors in whichever medium they prefer.

4. We Need to Respond to Physicians Seeking Warmth in Their Engagements

In our study of the psychology of engagement, we not surprisingly often hear physicians report searching for the “personal touch” in their engagements with pharmaceutical companies. Dealing with, and even avoiding, burnout can depend upon such human interaction.

Very positively perceived, for example, are lunches provided by representatives for the entire office staff. Interestingly, while some offices decline such engagements, those that partake typically do so three to five times per week. Doctors report that these lunches provide them with a way to reward hard-working, underpaid staff without any cost to the practice. And anything that brightens the day for the staff does so for the doctor as well.

Relatedly, the return of in-person “dinner meetings” in many geographic areas is well received by the physicians who attend, and who value the “congeniality” and “practical tips” that they encounter at such sessions.

One doesn’t usually think of emails as being warm or personal, but they can be. Physicians report responding positively to personalized emails written by their representatives and addressing their needs and requests, and negatively to those that arrive under the rep’s name but are nothing more than “package inserts.”

5. We Should Help Burned Out Doctors With “Drug Access”

With administrative hassle being a major cause of burnout, doctors emphatically tell us that we can be of great service to them by regularly “updating” them on formulary coverage for our products. Additionally, companies that offer meaningful assistance with “prior auth” are very positively perceived.

Also, physicians are extremely appreciative of drug companies that make their drug assistance programs for the financially disadvantaged both generous and readily accessible.

In Summary

While not entirely surprising, the guidance we have obtained through hundreds of conversations with physicians is profoundly important. In this post-pandemic era, more than ever we must recognize that doctors have a wide variety of preferences in terms of their engagements with pharmaceutical companies. We also need to recognize that these preferences represent strong habits, and thus are not readily amenable to change.

As a result, we must customize and individualize the engagements that we offer to physicians, making full use of today’s omnichannel environment to deliver these engagements. Luckily, our research has found that rather than being idiosyncratic in their engagement preferences, physicians fit rather neatly into a handful of “Physician Engagement Personae.” Identify the persona which best characterizes a physician, conduct research to understand the underlying psychology of that persona, develop engagements appropriate for that persona, and you are well on the way to mutually satisfying customization.

And one final thought expressed to me by a rheumatologist several months ago. In a quote that has been my guiding light ever since, she offered “The job of the pharmaceutical representative is to help me to help my patients.”

I would generalize this to suggest that the best way for pharmaceutical companies to deal with burned out physicians, and with all the other physicians who are at risk of burning out, is to have each of them be able to choose the kinds of engagements they wish to have with us, and then for us to deliver on those choices.

As another physician suggested in a recent conversation, pharmaceutical companies should be taking a “concierge” approach to engaging with physicians to help to reduce burnout.

Well said!