Clinical pathways are formalized processes of care designed to reduce treatment variability. They can also be referred to as integrated care pathways (ICPs) or care maps. While every medical case is unique, payers and providers are attempting to standardize treatment since unnecessary variation is a major source of growing costs. These formalized processes may take the form of treatment guidelines, decision trees, and triage criteria. Many Integrated Health Systems (IHS) are considering incorporating ICPs into their organizational strategy.

Clinical pathways serve to improve overall efficiency by:

- Managing the quality of healthcare with the goal of improving outcomes, via standardized care processes and reduced variability in clinical practice.

- Promoting organized and efficient patient care based on evidence-based practices, while considering specific patient population considerations including access to medications and insurance coverage.

The stated goals of Clinical Pathways are to reduce excess cost and improve the quality of care. Clinical pathways differ from quality-focused clinical guidelines in that clinical pathways are designed to achieve both higher quality and reduced costs.

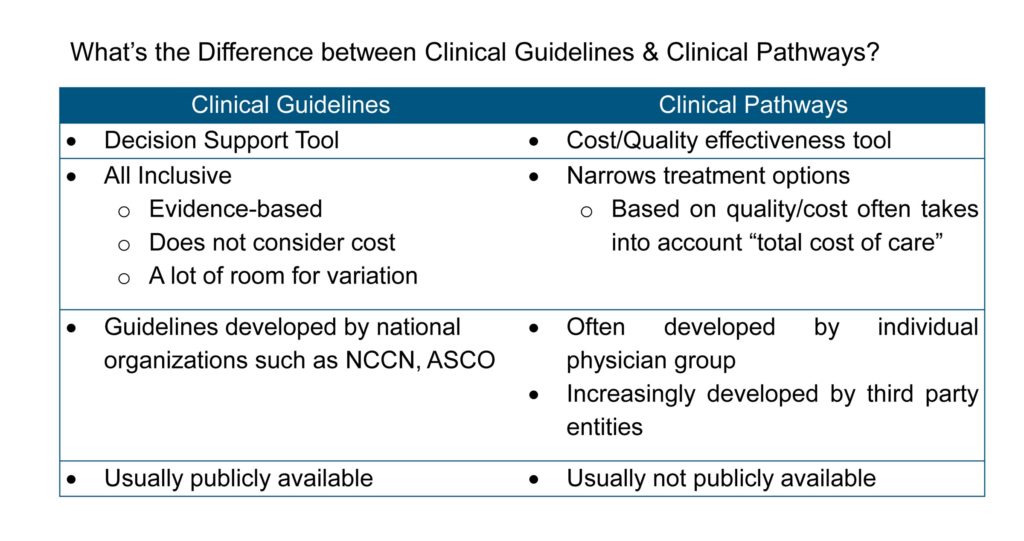

Then What’s the Difference Between Clinical Guidelines & Clinical Pathways? (Figure 1)

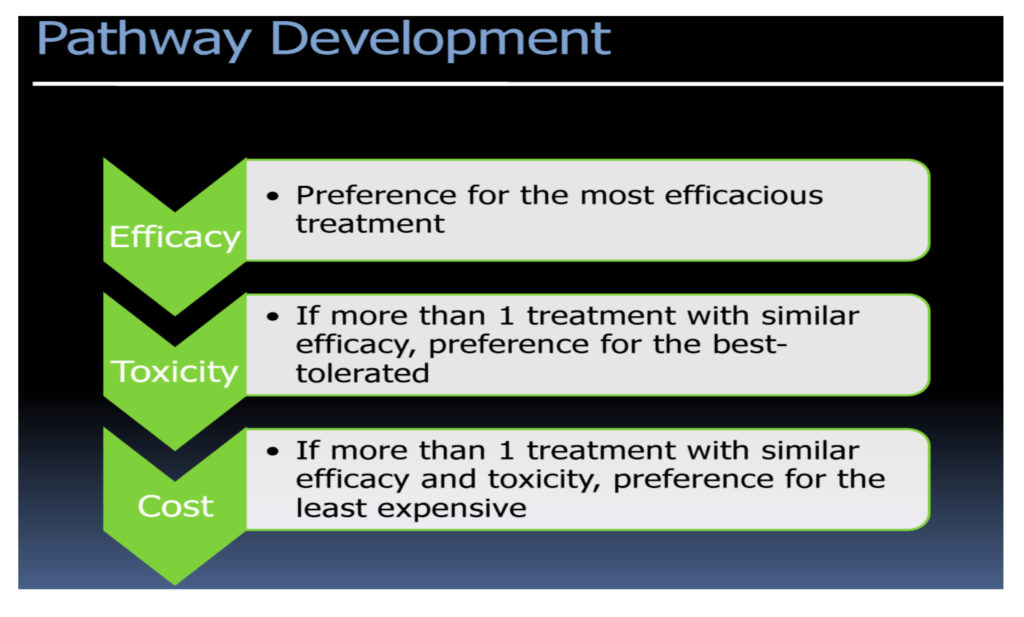

Clinical pathways are more solidified than protocols or guidelines because physicians and administrators expend significant institution-wide resources for pathway development and implementation. The goal is to take the numerous guidelines and apply clinical effectiveness, toxicity, and cost screenings to decide on a pathway—the best selection of near infinite guideline(s) to use. Most often, algorithms to derive effective pathways are driven by a top-down approach to narrow down the options based on efficacy, tolerance, and then cost. However, you see a spectrum of pathways being developed by different organizations, and the emphasis on cost varies based on the end user of the pathways. As the cost pressures on payers and providers increase, the shift in this algorithm is inevitable. (See Figure 2.)

Clinical pathways are more solidified than protocols or guidelines because physicians and administrators expend significant institution-wide resources for pathway development and implementation. The goal is to take the numerous guidelines and apply clinical effectiveness, toxicity, and cost screenings to decide on a pathway—the best selection of near infinite guideline(s) to use. Most often, algorithms to derive effective pathways are driven by a top-down approach to narrow down the options based on efficacy, tolerance, and then cost. However, you see a spectrum of pathways being developed by different organizations, and the emphasis on cost varies based on the end user of the pathways. As the cost pressures on payers and providers increase, the shift in this algorithm is inevitable. (See Figure 2.)

Once pathways are implemented, the goal is to use clinical information acquired at the point of care, or pulled from electronic records, to select the best of many guidelines or protocols to use. As a patient’s status changes, physicians’ and nurses’ access care pathway sheets are either physically or digitally available bedside. Depending on the stage of treatment and patient condition, the pathway document informs caregivers which of several clinically acceptable plans is the best to take. Due to the nature of these pathways, they are often used to make decisions for non-emergency cases with multiple treatment steps, such as oncology care.

Once pathways are implemented, the goal is to use clinical information acquired at the point of care, or pulled from electronic records, to select the best of many guidelines or protocols to use. As a patient’s status changes, physicians’ and nurses’ access care pathway sheets are either physically or digitally available bedside. Depending on the stage of treatment and patient condition, the pathway document informs caregivers which of several clinically acceptable plans is the best to take. Due to the nature of these pathways, they are often used to make decisions for non-emergency cases with multiple treatment steps, such as oncology care.

What is Driving the Uptake of Clinical Pathways?

Hospitals have long had loose guidelines or protocols in place that offer options for how to treat a condition. However, these care guidelines and protocols are only clinically focused. The sheer number of guidelines for a single procedure at an organization also means that care variation continues to occur. With the need to develop and track clear outcome measures, reducing variability is top of mind for all IDNs. Furthermore, hospitals are incentivize-based on quality outcomes and readmission rates, making predictability even more important. Pathways recommend the best option from a pool of care guidelines to effectively regularize delivery efforts across their institution. By standardizing care with both a clinical and economic mindset, pathways are an important value-conscious care strategy for providers and payers.

The quality of patient care varies based on numerous factors, such as healthcare setting, geographic location, access to medications, insurance coverage, and treatment protocols. Recently, the issue of whether the use of clinical pathways can reduce costs and inappropriate variability in care has been the subject of much debate. As clinical treatment guidelines and pathways are increasingly deployed, they have a growing impact on the quality of treatment and how it is delivered.

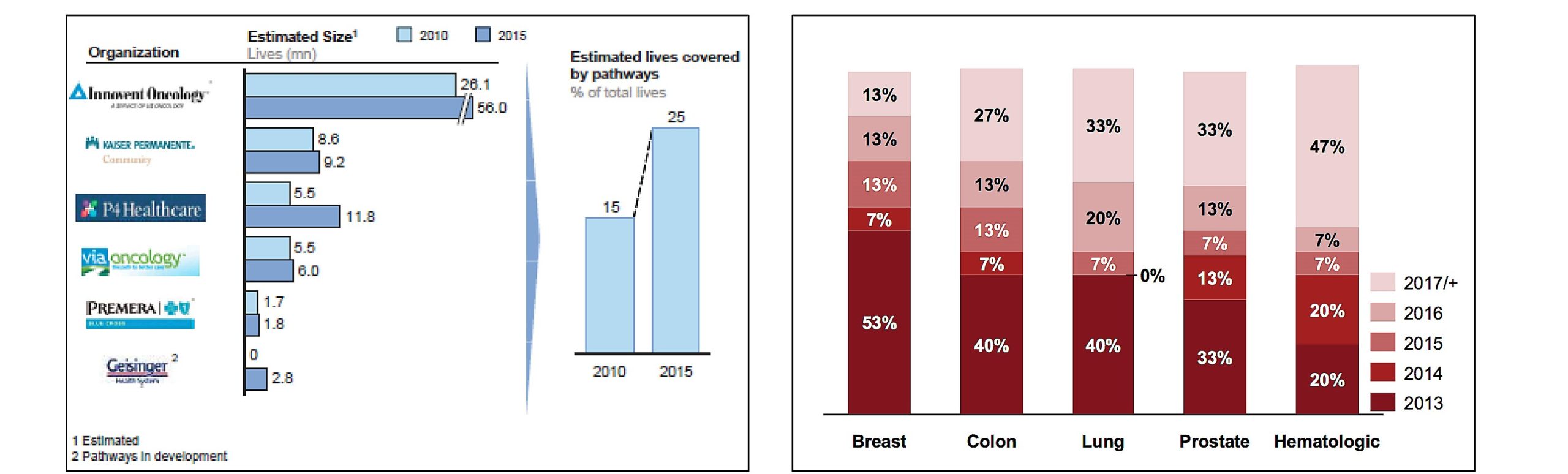

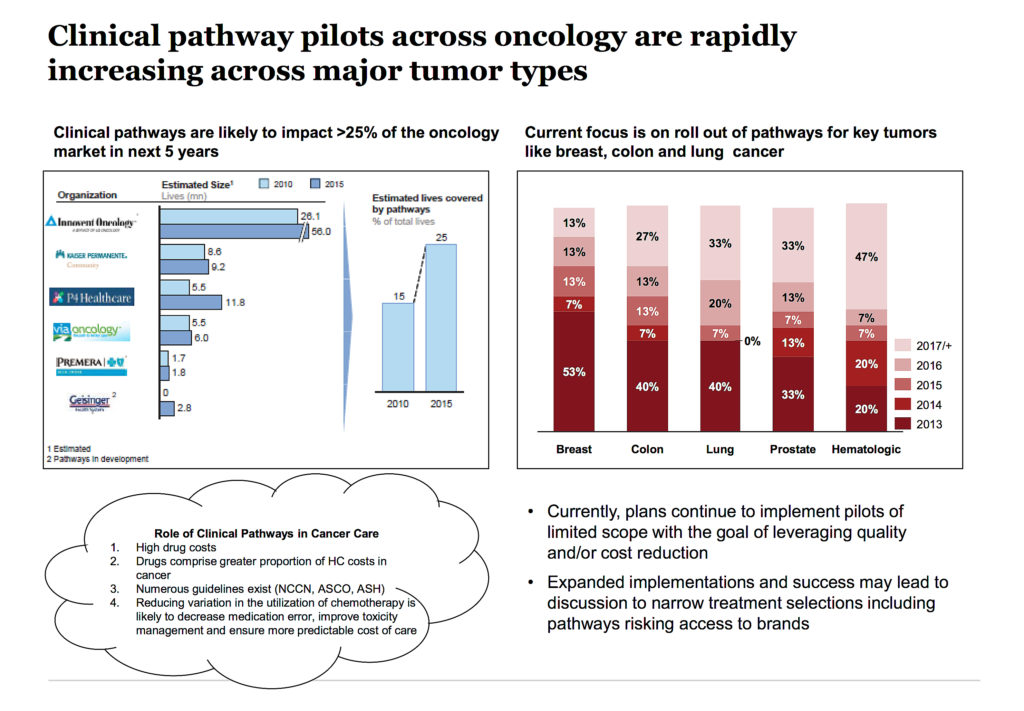

It is estimated that within five years, pathways could expand to include 25% of the oncology market as shown in Figure 3.

1. Implications of clinical pathways for providers: Pathways have probably been most popular in the oncology space, due to a lack of quality metrics and generally high pharmaceutical costs. As pathways are increasingly enforced, they fundamentally change the role of physicians, especially in a large consolidate provider setting like IDNs.

1. Implications of clinical pathways for providers: Pathways have probably been most popular in the oncology space, due to a lack of quality metrics and generally high pharmaceutical costs. As pathways are increasingly enforced, they fundamentally change the role of physicians, especially in a large consolidate provider setting like IDNs.

2. Maximize caregiver resource utilization: In many cases, pathways have also improved coordination between caregivers by giving nurses the ability to pursue a pre-approved care treatment with minimal oversight. This saves physicians time that they can then use to improve patient care.

3. Change of provider decision-making power: Pathways also potentially pose complications for hospital-physician alignment. It is imperative for health systems to gain physician buy-in when standardizing care. Any efforts to force pathways on caregivers are likely to fail. As a result, the Chief Medical Officer is often responsible for pathway formation and implementation.

Shift in Physician Incentives

Long popular at the local level, the geographic breadth of clinical pathway implementation is expanding on a greater scale in regional markets. This has mainly occurred as dominant local/regional payers, such as Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, encourage greater pathway adoption through increasing levels of financial reimbursement attached to provider pathway usage. National giant WellPoint has recently begun offering oncologists $350 per patient per month that they put on the insurer’s recommended clinical pathways. Many of these reimbursement models focus on how effectively providers can reduce pharmaceutical usage.

There are opportunities for pathway programs with built-in clinical decision support (CDS) tools that can efficiently identify patient-specific treatment, symptom management, etc. This helps provide the basis for payment for high-quality cost-effective care and helps predict utilization and cost of services, which could be effectively used in negotiations with payers. However, there are challenges to adoption of clinical pathways in terms of the need to incorporate pathways into the workflow, such as EHR clinical decision support tools, and one may have to manage multiple pathways and third-party vendor software programs—and after all these the impact is uncertain on patients’ outcomes, the cost of care, and parity of care. There is also concern about the loss of autonomy.

Although pathways may allow some clinical flexibility, pathway restrictions come in a variety of forms: Defined number of lines of therapy, a limited number of treatment options within each line, limited use of an agent to a single line, and delayed inclusion of a product. These restrictions may impact the care patients receive. In some cases, a physician may need to get approval from a group of consulting physicians to treat their patient in the desired off-pathway fashion.

The characteristics of effective clinical pathways are designed by physicians, evidence-based, updated regularly, informed through a formal physician feedback mechanism, evaluated for key data points on an ongoing basis, and monitored for minimum compliance.

Clinical Pathway Development Vendors

In addition to payers and national clinical organizations, many vendors are entering the industry to sell pathways to providers. Cardinal Health and McKesson both have built robust pathway development consultancies, and more specialized companies such as Nucleus Pathways, eviti, Inc., Via Oncology, and New Century Health provide more niche pathway development support.

While there are many reasons to institute clinical pathways, many pathways target perceived overutilization of healthcare products, particularly pharmaceuticals and imaging tests. Clinical pathways themselves are not designed to prefer one brand over another. But, the focus on controlling costs across providers oftentimes means that pathways incentivize the use of generic drugs over branded varieties.

There are a number of pathway developers, however, third-party vendors are most widely adopted.

- Payers/Health Plans: Health plans are developing/co-developing pathways to manage overall health plan operations and medical costs especially within key areas like oncology; ~40% of plans were developing pathways internally, based on a research study.

- Pathway Vendors: Pathway vendors and SCMs are at the center of clinical pathway development. Of the oncologists currently using pathways, approximately 80% currently receive guidance through one of the three developers: P4 Healthcare (Cardinal Health), Innovent (US Oncology), and Via Oncology (UPMC).

- Providers: Currently only very progressive IDNs have established/are establishing their clinical pathways, e.g., Kaiser Permanente. However, this is likely to evolve in the future as IDNs become increasingly sophisticated.

An immediate challenge involves a number of competing pathways with varied management approaches—Spectrum of Pathways from clinically driven (e.g., P4) to more restricted/enforced in terms of cost measures. Further pathway vendors are more provider focused compared to Specialty Care Management and hence are likely to influence IDNs in the future.

However, there are significant differences between pathways programs. Ask these questions of vendors when evaluating pathways for adoption:

- What is the scope of the pathways?

- How are the pathways developed and updated?

- How will the pathways be tailored to physician preferences (if at all)?

- What’s the typical/expected compliance rate? How long has it taken other organizations to get to this point?

- How are incentives realigned to encourage pathways use?

- What sort of IT infrastructure is necessary to support the pathways program?

- How is compliance assessed (internal prospective review and retrospective claims review)?

- What additional reporting capabilities does the vendor offer (will the institution be able to demonstrate cost savings/quality gains as a result of pathway use)?

Potential Implications of Clinical Pathways

Institution of clinical pathways at the system level can likely result in major changes to pharmaceutical and imaging usage:

- Downward pressure on pharmaceutical volumes: Pathways are designed to regulate dosage and minimize the use of pharmaceuticals. Due to this increased regulation of physician behavior, pharmaceutical volumes may drop for select conditions with strong clinical pathways.

- Decreasing latitude for off-label usage in certain areas as pathways dictate what types of pharmaceuticals should be used in certain situations. Certain off-label treatments may become difficult for physicians to use.

- Shift in the “key customer” for adoption: Pathways will lead to a shift in decision-making power within the IDN to be more centralized and at a higher level, thus making it challenging for pharma to sell drugs without demonstrating clear economic value for the ID.

- Evolving drug positioning needs: There will be a need to closely track the evolution of pathways and adapt product launch and positioning at the right time depending on the indication, especially in specialty products. For instance, perceptions on meaningful improvement in efficacy are evolving fast as vendors continue to optimize the pathways.

- Increased pathway development collaborations: Big pharma is fast moving towards collaborating with IDNs and payers to better help understand outcomes, quality metrics—a trend likely to continue a few more years before stakeholders are saturated. Capitalizing on this trend will be key to maintain positioning in a transitioning environment.

Conclusion

The following are the six drivers of pathway-driven treatment:

- Outcomes-based reimbursement with aligned incentives and increased collaboration

- Increased pricing/reimbursement pressure

- Health system consolidation

- Shifting roles for influencing Rx choice

- Value, not volume, focus

- New care delivery and consumer engagement platforms

As systems advance, IHS will influence prescribing behavior via protocol-driven medicine to limit brand access. Thus, it is important to segment evolving IHS early with a pathway lens. By engaging IDNs, pharma can tailor customer strategies based on the customer potential to limit brand access. Since 2011, we’ve seen a rapid uptick in health systems with advanced capabilities that are increasingly adopting clinical pathways/protocols.

Therefore, it is imperative for pharma manufacturers to gain a seat at the table for development of clinical pathways and protocols (and avoidance of bad ones).

- Move beyond the typical approach of building HEOR models to prove the value and instead invest in more innovative tools that enable payers/providers to measure value and outcomes in real time.

- Incorporate leading-edge thinking on Real-World Evidence to encourage different dialogues with payers and providers (e.g., re-classify old demographic information into smaller, more relevant and more actionable groups by combining data mining techniques across provider (EHR) and payer (ICD-10, CPT, and HCPCS codes) with learning algorithms based on associative word searches).

- Build case evidence to defend against adoption of poorly validated protocols.

Rx for Pharma:

- Understand pathway decision criteria and tailor trials and supporting data.

- Create differentiated value for assets especially in a crowded market.

- Understand the cost and value derivations for products in relevant therapy areas based on the plan segmentation to provide tailored solutions.

- Develop relationships to facilitate open dialogue with leading pathway vendors and committees.

- Create comparative effectiveness tools customizable to pathway segments.

- Tailor commercial model for stakeholder engagement based on emerging pathway models with priorities ranging from flexible SOC, technology/clinical solutions for improved quality of care, to financially incentivizing prescribers to adhere to pathways.

In light of pathway development, if you 1) identify implementation segments; 2) develop partnerships with pathway providers; and 3) develop clinical trials to meet market needs and ensure successful brand positioning with driving guidelines (e.g., NCNN) for plans, you are well on your way to establishing successful brand positioning.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are attributed solely to the author and not that of the company (IBM) he represents.