Virtually every company, every brand team and every marketing manager goes through the yearly ritual of developing and presenting the Annual Business/Marketing Plan. These plans can be very important because they determine brand direction, set expectations and help prioritize resources. Yet, as is often the case with many so-called routine company processes, if not done thoughtfully, they can be a long and sometimes pointless chore for both authors and audiences. Planning can be laborious, waste effort and, worse, produce plans that miss the mark resulting in organizational confusion and possible damage to the business.

Companies tend to approach this exercise differently, sometimes following standards, providing templates or using a structure and terminology that is specific to that company. However, there are common problems that are worth discussing, along with some ideas to make the process better, more meaningful and more impactful—regardless of a company’s structure, process or lingo.

1. Plans That Are Too Long

Simply stated, most plans and the requisite presentations tend to be too long. It is often said that if you can’t tell your strategy in a few sentences, then either you don’t know your business or you don’t have a meaningful strategy. An overly long plan can shadow or bury the most important issues, tends to lack clarity and can create confusion.

Some thoughts on root causes and solutions:

• There is such a thing as starting too early: Of course, a good plan takes time to develop, especially if the analysis is to be thorough. But work tends to expand to fill the available time so, invariably, work gets done, data gets analyzed and slides get created daily during the planning process. The longer the process, the more the deliverables.

• The wrong lead or team: Often, the annual plan is given to the new product manager to coordinate as a “development opportunity.” This is too critical of an exercise to have senior more experienced individuals participate only peripherally—and only when it’s time to dry-run for the big presentation. An inexperienced leader or team will tend to be hesitant about facing the hard issues or about coming up with breakthrough ideas; they will also err on the side of too much or too fuzzy information.

• Backup dumpster: This is a symptom of “just in case” mindsets. Rarely do back-up slides get used, yet they are all there, often hundreds of them, sitting ready to jump to their call for duty. What usually happens is that a lot of interesting information that was not deemed important or useful enough to make it to the front of the deck gets thrown in the back, just in case. It may be uncomfortable and hurt a bit but, just like the film director, it is okay to leave things on the cutting room floor.

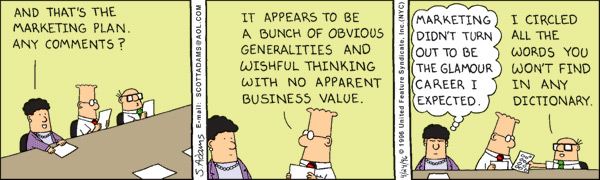

2. Template Prison

Templates can be very useful because they bring discipline, consistency and a general framework for thinking about expectations and deliverables. However, people have tended to follow templates to the letter and have become obsessed with the task of filling them, taking time and effort away from critical strategic thinking. Inflexible templates can handcuff and misguide teams in ways that prevent innovation.

Templates should still be developed and provided because they do offer a roadmap and can save time and ensure some consistency and common language. However, they should be a guide and not a mandate. Teams should be given the freedom to deviate if they feel it is appropriate to do so to tell the story; this can do wonders to free their imagination. One helpful solution is to indicate which subset of analysis or content is mandatory and which is not—keeping mandatory content to a true minimum.

3. Analysis Paralysis

Clearly, a robust situational analysis is critical for making strategic choices. The problem is that companies have become plagued with too much information that gets collected, analyzed and regurgitated. With so many new sources of up-to-the minute information on everything from broad markets to individual physicians and patients, it is very tempting and seductive to try to get and use all of this data. It’s like building an even higher haystack for the same proverbial needle. But is all of that really needed for good decision-making?

Admittedly, much of the collected data may be interesting to know and looks great on slides, but in reality it may not be actionable or relevant for the strategic questions that need to be asked and answered. A more useful, albeit more uncomfortable approach, is to do data analysis and collection in two stages, the first to establish historical patterns, describe current behaviors and buying processes, market preferences, competitive trends, etc. Then going into a phase of identifying and defining strategic alternatives and the key questions that must be answered to choose among those alternatives. Only then can you go after the additional data required.

As a general principle, not necessarily associated with the annual planning process, a yearly complete inventory of all data purchased and reports produced is a worthwhile exercise. This should include a survey of how much and to what extent the data and reports are being used to make business decisions. Most companies will be surprised at how much is underused and is either important and should be used more or should be discontinued altogether.

4. One Size Does Not Fit All

Companies with multiple products like to follow a one-size-fits all model for all of its products for consistency. Teams run around scrambling with the same timelines to meet, templates to fill and presentations to prepare—regardless of the age of the product, its stage in its lifecycle or its degree of marketing complexity.

Management would do everyone, including themselves, a huge favor—and save a lot of resources too—by stratifying its products into two or even three groupings. Each group should be assigned different delivery expectations based on what is new, the nature of the dynamics on its market (e.g., no new products or data versus many new products and studies), likelihood of major strategy shifts and other parameters.

5. Not A PhD Dissertation That Needs Defending

Now, all the right people have been assembled and the download begins. What also often begins is the second-guessing and the positioning and grandstanding by some in your audience. This of course will vary greatly from company to company and team to team and is a product of both company culture and leadership abilities and styles. It is not my place to judge the merits or harm of this; suffice to say that leaders should give thought to these habits in the context of not only successful business planning but also employee motivation and retention. Careers are often made or broken on a single business plan presentation. Expecting marketing teams to “know their stuff” and think on their feet is a fair expectation; however, overplayed challenges and public hangings can have an unintended consequence of shutting down discussion, creativity and engagement.

A few tips to help make this all important presentation day be more productive and perhaps less stressful:

• Preview and pressure-test key assumptions, conclusions and recommendations with as many people as possible, especially influencers and decision-makers, making sure the story is clear, concise and something they would be willing to support.

• Instead of sending whole decks of slides ahead of the presentation, consider sending out only a brief one-page summary with background only, not recommendations, to bring everyone up to speed.

• If you are in a senior position, provide the leadership to ensure open discussions and avoid/stop others’ grandstanding and attacks; after all, this should be a discussion not a download or an inquisition.

6. Don’t Confuse Planning with Budgeting

There was a time where a single phase existed for strategic planning, tactical planning and budgeting, sort of an all-in-one exercise. Some companies still do this, but most have evolved and separated the strategic planning phase from the tactical and budgeting phase. An issue with the all-in-one approach is that, besides taking place too late in the year to be adaptable, it is locked in and has almost committed the tactics and budgets to a particular strategy that has not yet been vetted. Inevitably, most of the discussion go to tactics and budgets and the more difficult, and admittedly fuzzier, strategy discussion is short-changed.

Marketing issues and opportunities have become so complex that that they deserve a focused review and assessment. Strategies (not implementation) need to be fully assessed, reviewed, tweaked and agreed to before being able to build tactical plans and budgets. Of course, this separation can mean a longer planning cycle, with situational analysis likely starting earlier in the year (and requiring periodic updates), but the benefit will be more thorough strategies leading to more appropriate tactics.

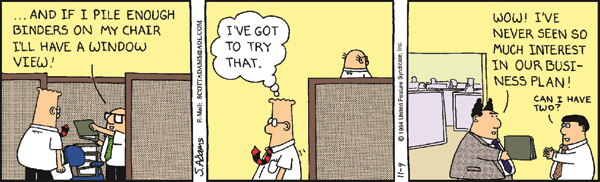

7. Shelves Full of Binders

The sad reality is that many plans tend to go to sleep the day after they get presented. Shelves (or their electronic equivalent) are full of thick binders that will never or, at best, seldom get referred to. Strategic and tactical planning must be a continuous, living process. Markets and environments are too dynamic to rely on observations, assumptions and decisions made nine to 15 months earlier.

Another frequent gap is that in many strategic plans, little thought is given to the realities of execution. Now this may sound contradictory to an earlier recommendation that highlighted the importance of separating strategic planning from tactical planning. However, without a need to fully flesh out the tactical plan, there can still be consideration for execution realities while developing strategies. If it is evident that there is no likelihood that a certain strategy could ever come to fruition then it is not a viable strategy and should be abandoned or adjusted early enough. Some of these execution barriers might be: Laws, regulations and compliance; data and labels; or large gaps in capabilities or capacity.

Some tips:

• Pressure test major strategic moves with your clinical, regulatory, legal and compliance teams. Nothing can be more wasteful than going through the whole process and settling on a strategy that simply cannot be pursued. You are not asking for approval at this stage, simply for potential feasibility. This should help you uncover major gaps or landmines that either can and should be overcome, or need to be taken to heart and help you steer away from the direction you were thinking.

• After all is presented, discussed and agreed, a very brief summary of the key findings, assumptions, goals and recommendations should be produced and kept “alive” throughout the year. This should act as key reference for tactical planning, for regular business reviews, for agency briefings, and so on.

• A living business plan will ask along the way:

o Are you still doing the right things? (i.e., Are you on track and should you stay the course?)

o Can you do things better/faster/cheaper? (i.e., make incremental/adjustments.)

o Can you or should you do things quite differently? (i.e., seek major innovation or transformational actions.)