My first day on the job, in pricing for the Upjohn Company in December of 1980, Senator Ted Kennedy gave a speech in which he vowed to bring the pharmaceutical industry to its knees because they charged such high prices (at the time Motrin, Upjohn’s biggest product, cost about 75¢ a day). Eleven years before that, George Squibb published an article entitled “Drug Prices—the Achilles Heel of the Drug Industry.” Suffice to say, drug prices have always been controversial, unpopular and under attack. The current torrent of articles, blogs, papers and speeches decrying pharmaceutical prices are not new but they may be different, and not because of actions by the pharmaceutical industry.

Let’s get this established right up front: Nobody wants to have to pay for medicine, period. People would rather not have illnesses; they purchase medicine because they have to, not because they want to. I have written about this topic many times,1 and won’t hash it over again here, but essentially, drug prices will never be low enough to satisfy people. That said, what is different today is that health insurers seem to be going out of their way to make medicines less affordable and to actually cause patients to start to skip them. How can this be? Let’s look at some facts:

- Patient compliance and adherence is greatly affected by out of pocket costs. Insurers know this, and Caremark proved it.1 They also know that this leads to higher costs and worse outcomes. Despite this (or perhaps because of this) they are increasingly shifting more costs to the patients and increasing copays.2

- With cost shifting, more patients are opting for high-deductible, low monthly premium plans, which make out of pocket costs for drugs even higher.

- The current market environment forces insurers to ignore long-term savings and favor short-term cost reduction,1 which helps explain the previous points.

- The current structure of pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement is about as complex as the U.S. tax code—and getting worse. This leads to mistakes and bad decisions on the part of almost everyone.

- Because 80% of prescriptions are for generics, patients have become accustomed to “Drug prices” of $5 to $10 per prescription, making even a second tier copay of $30 sound high, and a third tier cost of $60 seem like price gouging!

- By using contracts and restrictive formularies health insurers have established discrete benefit sets, favoring one drug over another. This means that patients must understand their insurance coverage and how it relates to their drugs, and hope nothing changes.

I have discussed the first three points in the past and written a couple of books about the third—I won’t cover them now. But the two final points deserve some attention.

Confusing Choices Faced

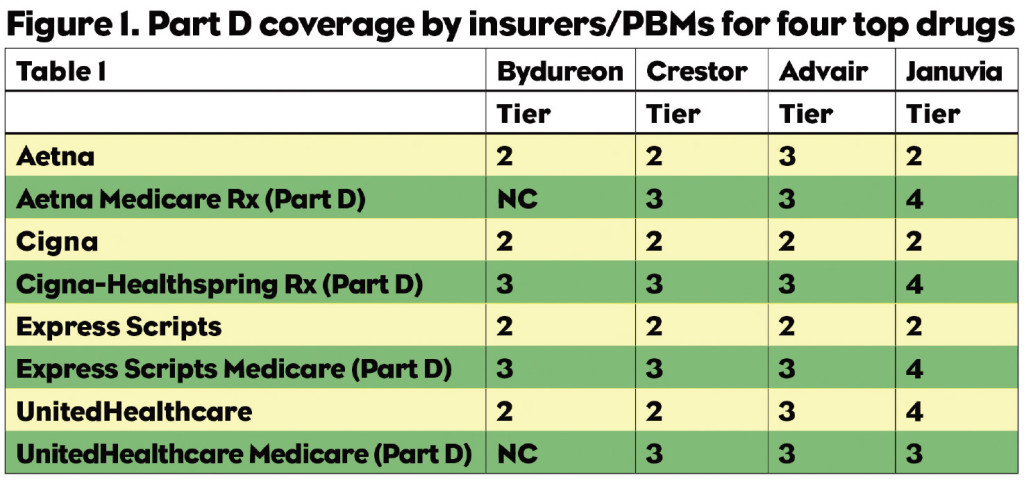

Pharma companies and patients alike are subjected to a confusing and perhaps insidious set of choices. Figure 1 lists four top selling drugs and their coverage by three health insurers/PBMs. Note that a patient with Aetna on Bydureon pays a second tier copay for a prescription, about $30. When they turn 65, if they get Aetna’s Part D coverage, they would pay full price. The Humana patient who is paying a third tier copay for Advair would also find themselves paying full price when moving to a Part D plan. Crestor patients in all plans would see their copays increase, and the Januvia patient with Aetna or Express Scripts coverage is in for a big shock when they turn 65.

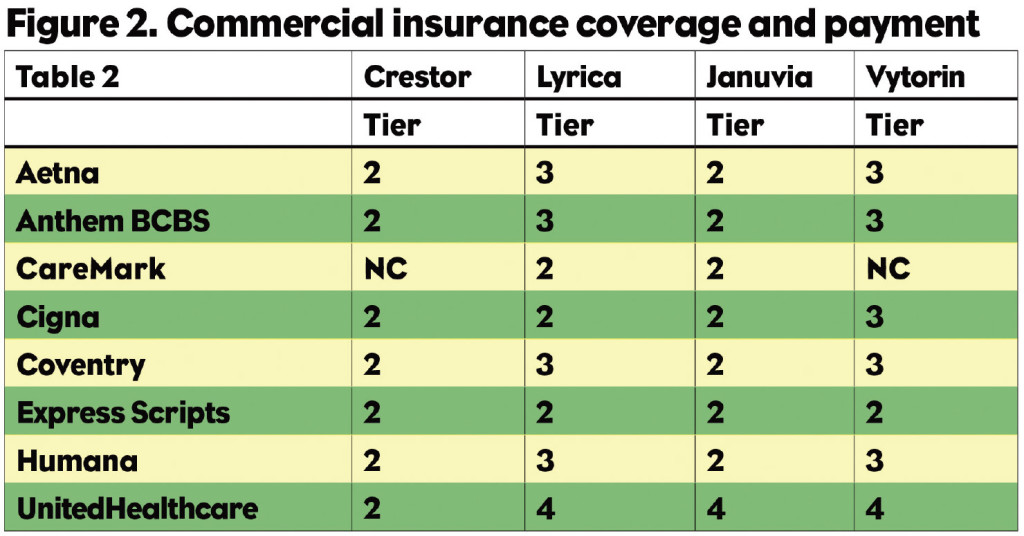

But it isn’t just seniors who get hit. A patient with a commercial health plan who changes jobs, or whose employer changes insurers, could be in for a shock as well. As Figure 2 indicates, the Crestor patient with Aetna or any of a number of other payers has a second tier copay, but switch to Caremark and the drug is not covered. The same thing happens to the Vytorin patient. In all of these cases the patient is most likely to blame the drug company for “raising their price”—not their insurer. They will then inform their HCP about this egregious behavior, and some of the docs will change their prescribing practices. This isn’t a pricing problem, it’s a coverage problem, but guess who gets blamed?

Payers Prefer Generics

And don’t think that you can contract your way out of this problem because most payers are not interested in letting you get your product to second tier through a contract. They would rather have the patient walk away from any brand and trust that they will ask for a generic instead. For the foreseeable future, almost all branded medicines will be viewed as overpriced because insurers benefit (in the short run) when brands aren’t used.

What can you do about it? You have two choices: Point out what insurers are doing, which might be risky. Or, sit back and take it, which is even riskier. Marketing managers and sales reps alike need to understand the basics of prescription reimbursement, and understand how that affects the use of their products. Failing to do this will lead to some big disappointments in the coming years. Pharma (or someone) needs to draw attention to the problem of insurers working against the best interests of patients and their health. Brand teams and sales reps need to be able to explain to physicians that a $60 copay is still a great deal relative to any alternative. If you can’t say that about your drug you really need to revisit your value proposition.

Resources:

1. Kolassa EM, “The Immense Benefit of CoPay Cards,” PM360, June 2012, pp 30-31.

2. Elise Gould, “Increased Health Care Cost Sharing Works as Intended,” http://www.epi.org/publication/bp358-increased-health-care-cost-sharing-works.

3. Kolassa EM, “Why Are Payers Blocking Hep C Drug Accesss?” PM360, June 2015, pp 26.